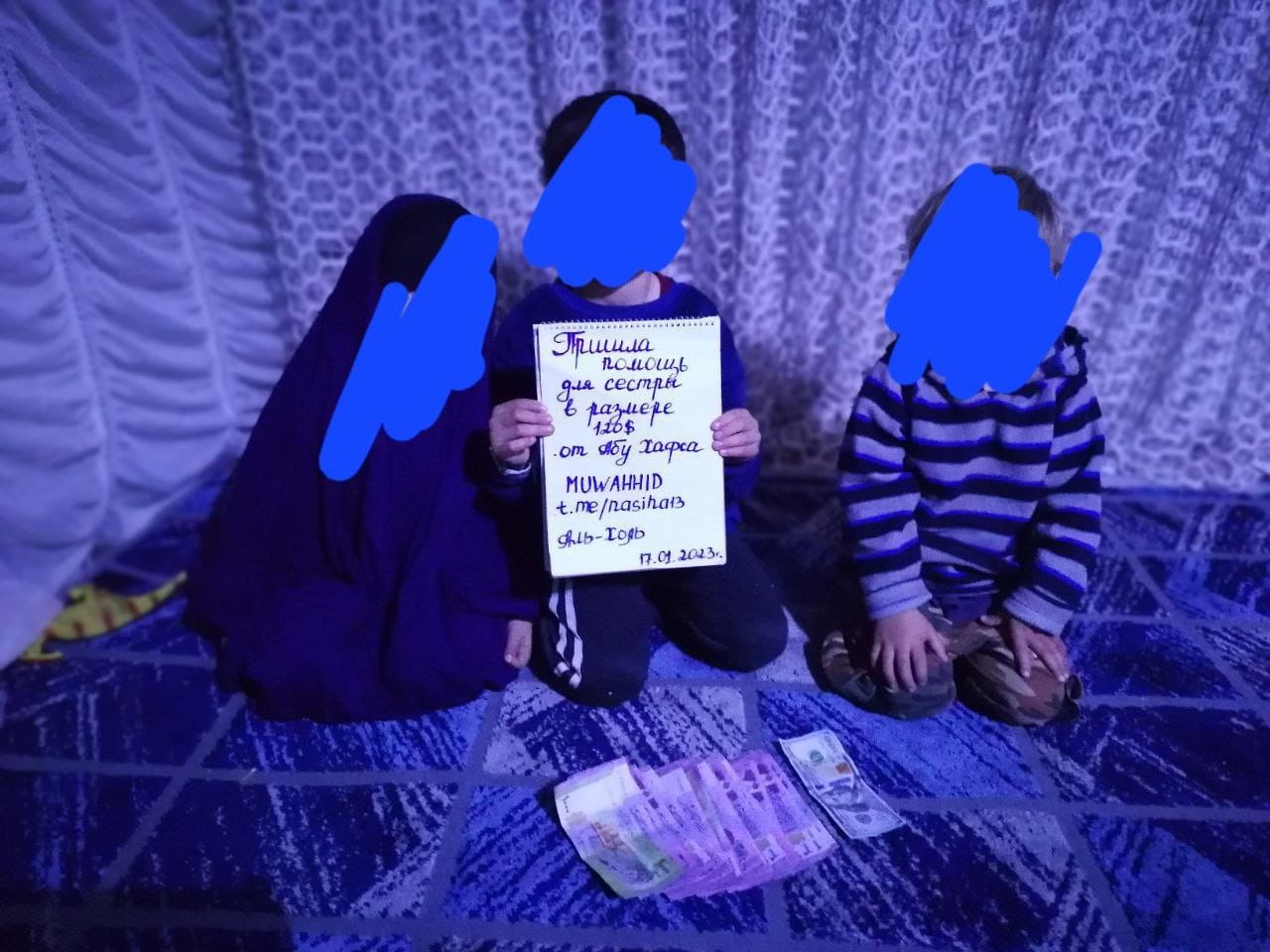

Mona Thakkar & Anne Speckhard Despite notable repatriation progress in early 2023, involving 14 countries…

Jesse Morton: A Story of Trauma and Radicalization

Anne Speckhard and Molly Ellenberg

As published in Homeland Security Today:

The impact of trauma on radicalization and terrorist recruitment has only recently made its way into the collective psyche of counterterrorism researchers and practitioners and is still not well understood. What does trauma, especially during childhood, do to individuals to make them more vulnerable to radicalization and recruitment, and what do terrorist groups offer these individuals that they feel they did not previously possess due to their histories of trauma? Jesse Morton is closely acquainted with these questions. As the child of counterculture parents, Jesse grew up isolated, away from neighbors to whom he could turn in the face of abandonment by his father and brutal abuse from his mother and he learned that reporting the abuse at school just earned him a worse beating at home. As he explained to a Zoom audience of hundreds in a panel hosted by the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism [ICSVE], his earliest memory is of “my mother laying on top of me in the farmhouse suffocating me, the light pouring through the curtains in the big farmhouse widows, her blazing down on my face and me thinking that I was actually going to die.” Jesse notes that each of his siblings had a different role and response vis a vis his mother’s abusive behaviors. His sister, he recalls, reacted to the abuse with meekness, never wanting to cause trouble. This withdrawing coping strategy common among abuse victims is one that in severe cases may develop into dissociation. Jesse’s brother was not abused, which Jesse now realizes was his mother’s way of rationalizing her treatment of Jesse: if she was not hurting all of her children, it must not be her fault that one child was deserving of abuse. Jesse realizes now that he was the “black sheep” persona or scapegoat in his family, the poison container into which his mother poured all her rage, frustration, self-hatred and sense of failure.

Now reflecting on how many “black sheep” who become radicalizers and recruiters he realizes that they see themselves as bad, but also as protectors who take abuse so that others don’t have to. Likewise, Jesse reflects on a world that failed to protect him, ultimately causing him to rage against it. Time after time, “I never experienced an ounce of compassion.” When he was 15, Jesse “went into a guidance counselor at school and told him I was being abused and he called my mother and, long story short, she said I fought with my brother over that weekend and that I simply make stuff up.” When he returned home, he received one of the worse beatings of his life. Realizing that there were no protectors who were going to end the abuse, he ran away from home to live on the streets shortly thereafter. In examining Jesse’s early life, the needs and vulnerabilities are clear. This was a child who believed that no one loved or cared about him, who believed that he did not belong anywhere, even in his own family, and who saw the injustices perpetrated upon a child overlooked by a hypocritical society that purported to be just.

After leaving home, Jesse searched for acceptance wherever he could find the love and nurturance he needed and having a seeking mind he read about social justice movements and searched for answers to society’s failures to protect. He traveled with the Grateful Dead in the mid-1990s, used and dealt in drugs, enjoying introducing youth to a new counterculture experience of tripping on acid. His lifestyle eventually culminated in his arrest and being jailed at age 18. In the prison library, Jesse, still seeking for answers, came across the autobiography of Malcom X. “I read it three times in a row.” Jesse saw himself in Malcom X. He too had been oppressed and subjugated and treated with violence, not by societal institutions but by his own mother, but Malcolm grew to be a fiery leader whom Jesse wished to emulate.

As a child, Jesse found that the only way to maintain his sense of self was to stand up to his mother. He held many of the same far-left views of his father but knew from his own experience that pacifism could not bring about real change. As he explains, “I wanted to tear down the world around me because the world didn’t protect me.” Reluctant to blame only his mother for his lot in life, “I blamed our society; I blamed America.” And thus, recounts Jesse, he “completely adopted the religion of Malcolm before I had any contact with the religion of Muhammed.” As ICSVE director Dr. Anne Speckhard noted during the Zoom event, researchers are too often reluctant to acknowledge the legitimate grievances that Muslim youth experience and that terrorist groups use as recruitment tools. Indeed, many foreign terrorist fighters [FTFs] joined ISIS in order to defend the Syrian people against the atrocities of Bashar al Assad, whom Western leaders verbally condemned but failed to stop. When researchers, practitioners, and intelligence agencies ignore the real struggles and concerns of individuals vulnerable to radicalization, they miss a key opportunity to thwart the efforts of violent extremist groups who exploit these real grievances and offer answers and action.

To Jesse, Malcom X was “a martyr and a social justice warrior as far I was concerned. I wanted to live that and manifested an ability to live that from the time they let me out of that jail stint.” While Jesse searched for his paths to emulate Malcom, he continued in his criminal lifestyle, through which he had found a sense of belonging, but he also understood that he was devolving further and further, using crack cocaine and heroin to his own detriment. For Jesse it wasn’t until he was arrested again when he met a Moroccan recruiter who was a veteran of the Afghan-Soviet jihad that he found real answers – this time in Islam and militant jihadism. “He taught me a religion that gave me stability and offered me a sense of, ‘OK, I don’t have to use alcohol and drugs any longer.’ He taught me the five pillars of Islam. And one day he told me that ‘you’re actually ready to become a real Muslim.’” While his recruiter first addressed his needs to clean up and to belong, he later also taught him to use violence in pursuit of social justice and warned him of an impending war between the West and Islam. Jesse took this viewpoint full on and first cleansed himself in order to be born again. With his new mentor he recited the shahada and took a new name as he also adopted a new identity. As he recalls, “I had come to hate everything I knew about Jesse Morton, so he told me that my new name was Younnes Abdullah Mohammed.” His first name, Younnes, was especially meaningful. In the Bible, Younnes (Jonah) was swallowed by the whale after resisting the command of God to tell the people of Nineveh to repent and upon being spit out brought the word of Allah to all around him, saving them all from God’s wrath. The trauma he had experienced transformed him into being the best messenger of Islam. Jesse took this to heart. After being victimized by his mother and also being trapped in drug abuse and prison – living in the belly of the whale – Jesse finally had the opportunity to be spat out and to use his voice to defend not only himself but victims all over the world. In reaction to his trauma, Younnes Abdullah Mohammed became the successful, fiery protector and defender of young, helpless and failing Jesse Morton, as well as for other Muslim victims of Western oppression. Realizing the Western societal order had failed him, he grew to want to tear it down, destroy and replace it with something better – a just and orderly Islamic shariah-governed world.

After his conversion and release from jail, Jesse sought treatment for his drug abuse and ultimately joined an Islamic community in Harlem made up of people who had been affiliated with Malcom X. The group operated a homeless shelter and substance abuse recovery program, providing a holistic system of belonging for Jesse. Jesse also discovered the Islamic Thinkers Society, the analogue movement of al Mahajaroun that worked toward replacing Western governance with Islamic shariah. He “started preaching on 125th Street against the Iraq war, and mobilizing African-Americans to convert to Islam to ‘reclaim’ their original identity.”

Jesse mobilized all his hurt and rage over childhood trauma as well as his considerable intellect and ability to articulate on behalf of a social movement and quickly gained power and influence. “Because I was a white guy with blue eyes, I was rather effective, and I knew how to speak. So, I was empowered,” he recalls of his rise from failure, pain and shame to a narcissistic headiness of leading others toward his rage-filled vision.

Jesse became more associated with a U.S.-based Salafi jihadist group in 2004, and in 2007 took the lead in bringing their ideology online. While he was helping to promote al Qaeda propaganda, much of his work became the precursor for ISIS’s amazing online success. Jesse understood how to utilize YouTube and interactive platforms and created a website that, in addition to discussing religion, “framed progressive politics and revolutionary politics in an Islamic way.” Jesse and his partners named their movement Revolution Muslim. Their extremist and eye-catching stunts, published not only by themselves but also broadcast by mainstream and right-wing media, attracted a small group of like-minded Muslim individuals who saw them as the only people standing up against the atrocities of the world. He brought these individuals to his website and chatrooms, “a one-stop shop for ideology,” and together with Samir Khan and Anwar al-Awlaki, Jesse founded the first English-language jihadist magazine, Jihad Recollections. Understanding how to frame al Qaeda propaganda for Western audiences and Western eyes he designed its pages in slick eye-catching titles and pictures that later formed the basis for ISIS’s Dabiq online magazine.

Ever the effective messenger and understanding the appeal of emotions and online interactivity to rope people in, Jesse wrote the magazine’s lead articles and “made it look like Vanity Fair for al Qaeda in the United States.” The magazine, he explains, was used for emotional appeal. It would draw people to their chatrooms, where the ideology and narrative would be cemented. Jesse and his cohorts made headlines around the world. They forced Comedy Central to censor an image of the Prophet Muhammed on “South Park.” They issued a death threat against a woman who organized an “Everybody Draw Mohammed Day Facebook group”. Jihad Recollections later morphed into al Qaeda’s Inspire magazine, which published the now infamous article, “Make a Bomb in the Kitchen of Your Mom.”

Jesse fled to Morocco after a post to his website, written by a follower, threatened the writers of South Park, triggering arrests. Morocco became a refuge where he lived for a year before being arrested. Running away to Morocco and evading authorities forced Jesse to distance himself from the extremist network in which he had become so entrenched, as he knew he would be arrested and did not want to implicate his comrades. Removing himself from the militant jihadist network, though not in an effort to disengage and deradicalize, but rather to evade arrest, was a first step in Jesse’s journey out of violent extremism. In Morocco, he worked teaching GRE and GMAT prep courses. He also began witnessing and spoke with his young students about the burgeoning Arab Spring. As he watched he realized the real answers to the Arab world’s ills might be coming not from his militant jihadist movement, but from the people themselves. He remembers, “One woman really challenged my views and perspectives and I started to really understand that I had become an authoritarian dictator, whereas my original roots didn’t believe in forcing things on people from above.” As he explains, he and his jihadist cohorts were trying to liberate the Muslim world, but the people they were trying to liberate wanted nothing to do with them. In this way, the pro-democracy narrative of the Arab Spring began to chip away at his existing narrative.

Jesse was ultimately arrested and sent to prison in Morocco before being extradited to the United States. In the Moroccan prison, he met a deradicalized Salafi jihadist, Mohamed Fizazi, who may have been planted, who spoke to him not about that ideology, but about his personal life. Fizazi took Jesse by the hand, offering him genuine care that he had never received from his parents. He asked Jesse, who was facing life in prison in the U.S., “why I threw away my life for something that I didn’t have any actual trained knowledge on.” Indeed, Jesse, who had been forced to rely on his own wits too soon when he still longed to be nurtured, was offered compassion in his darkest days. Back in the United States, a prison guard also showed compassion by taking him out of solitary confinement to the library regularly, where he “fell in love with enlightenment philosophy, with critical thinking” in the post-Arab Spring, Occupy movement era. Back in his cell Jesse recalls, “I started to read the Quran again, but with a post-enlightenment perspective.” This critical approach to religion was an important step in helping Jesse to slowly dismantle the militant jihadist narrative. Having had no formal Islamic education, Jesse had memorized what he was told to memorize by his newfound friends in the Revolution Muslim movement and operating from hurt and anger he resonated to claims of grievance and purported solutions that claimed to bring justice to victims. He then sought out only those preachers who reaffirmed what he already believed. Years later, he was able to once again approach Islam with a new lens and learn how wrong the ideology he had been taught was and how unlikely it was to deliver any real justice or heal any of the hurts in his soul.

Jesse pleaded guilty in U.S. court and agreed to work with the FBI, as his students and former colleagues were beginning an exodus from the United States to join what would soon become the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria [ISIS]. In the FBI’s Behavioral Analysis Unit, Jesse was again met with compassion and respect from people who wanted to learn from him and were “not concerned with waging a war on Islam but concerned with understanding how to better combat the fringe extremists who carry out violence in its name.” The judge who sentenced him to eleven and a half years in prison told Jesse that he hoped he would become a positive force in the world upon release. Jesse was released nearly four years later. In that time, the Boston Marathon bomber used the recipe Jesse had helped to promote online to kill three people and injure hundreds of others. Horrified by this, Jesse vowed to spend his life making amends for the harm he had caused, beginning first as a confidential informant for the FBI. This entailed returning to his community that had welcomed him so many years prior and pretending that he had gamed the justice system and still shared their beliefs and violent goals. Ultimately, he was exposed by an imam at a bond hearing who claimed that Jesse had entrapped the arrested jihadists about whom he had served as an informant to the government. In that moment, Jesse was officially expelled from the community that had long ago brought him meaning and purpose when he needed it most. He thought he was ready to be done with them, but in actuality he still had a lot of healing to do from his violent and traumatic childhood and his history of relying first on drugs and sex to deal with his emotional distress, and later fanatical religious beliefs. Unmoored from the militant jihad which had steered his rage and replaced his shame with endowing him with a leadership role he was at a loss – but opportunity soon filled the gap. However, Jesse had walked away from militant jihad, informed for the government, seemingly overcome childhood trauma and a history of drugs and alcohol abuse, yet in reality no one had thought to offer him any real rehabilitation support or therapy to overcome all of these challenges. Despite this, Jesse walked into his new role as a countering violent extremism expert.

Jesse went public as America’s first former jihadist as he was hired and promoted by the George Washington University’s Program on Extremism. He spoke about his childhood trauma in an interview without realizing the inner pain that might evoke, not to mention his family’s response. The interview resulted in rebuke and rejection once again by his mother when the interview was published. Jesse felt like he was doing good in the world, but he didn’t relate to the privileged people he was suddenly working with and seemingly belonged to. Likewise, the needs that had previously been met by drugs and jihad still existed: “The opiate of ideology was gone, but the things that made me an addict were still there.” He unfortunately relapsed into substance abuse and was incarcerated once more, causing a fall from grace and resounding pubic shaming.

Now, much wiser about his attempt to overcome his childhood trauma and rehabilitation from his involvement in the militant jihadist movement he understands that he needs both support for overcoming his childhood pain and for replacing the negative coping mechanisms he first used with more effective and positive ones. A gift from the pain remains, however. Jesse explains that nowadays he works diligently to understand the role that trauma plays in radicalization and the way that not dealing with his own trauma led to his self-destruction over and over again. He realizes that when he lost the dangerous network and narrative of militant jihadism, he needed to replace them with positive coping and building yet again another identity shift in order to meet his needs and find his place in the professional world. He also knew that vulnerable youth like he had once been would also need a prosocial network and narrative if they were to be steered away from violent extremism. Understanding that and sensitivity reading into their needs he now works to create a network that can help others.

Now, Jesse runs a nonprofit organization called Parallel Networks. With Parallel Networks, Jesse works to “reverse engineer what I built with Revolution Muslim,” that is, create a holistic ecosystem to counter violent extremism. He works to identify the needs of people on the verge of radicalization and offer them a narrative and network that can offer them the meaning and significance they crave, without turning to militant jihadism. Mirroring the strategy that Mohamed Fizazi used with him, Jesse speaks to radicalized individuals first about themselves and their experiences, long before he broaches the topic of ideology at all. He acknowledges that he uses the same skills in his current work that he used as a recruiter in his former life. Too many organizations, he believes, focus on only one aspect: messaging, intervention, or prevention. Terrorist groups do all three, and a truly effective program must be able to do all three as well. Jesse’s Parallel Networks partner is the former director of intelligence for the New York Police Department, who monitored him for five years, and taught him how to work to improve himself and to make amends going forward.

In many ways, Jesse’s story is a cautionary tale. Unabated and unaddressed trauma that one experiences in early life can have an immense impact over a lifetime causing self-harm and harm to others. This is also compounded by the hurt and anger that comes from the failure of others to step in and help. The abuse to which Jesse was subjected by his mother could have been damaging enough on its own, but his father’s abandonment and his school’s neglect and ineptitude in intervening taught him that no one was coming to rescue him. The only way to be saved, he learned, was to do it himself and to do it with force. And later he would also advocate for forceful solutions to help save other Muslim victims with whom he strongly identified. Jesse also desperately sought belonging, acceptance, and purpose. He found them first in the world of drugs and drug dealing and later in the world of militant jihad. In the latter, he showed how successful and creative he could be with a network of support. Jesse discovered his skills of creativity, persuasion, of public speaking, of appealing to people’s emotions, and of driving people to action, but because of his own unaddressed hurt and rage over his own victimization and his latter identification with Muslim victims in general and due to the network and narrative to which he was exposed, he used those skills to incite violence. He now recognizes, even with the understanding of the harm his action caused, that the work he did for his movement made him feel special and worthy of recognition, not only by his peers, but by God. It wasn’t easy to step away from that, but he managed to do it and begin to rebuild himself in yet a new identity, one that he is still working to make strong and effective in helping victims, without harming others.

Jesse’s story also demonstrates the power of trauma to create strong vulnerabilities to radicalization and also the power of compassion to reverse that course. Even after advocating for militant jihad and propagandizing in ways that undoubtably led to acts of terrorism, Jesse was shown empathy, first in the Moroccan prison and later at all levels of the United States justice system: a judge, a prison guard, an NYPD intelligence director, and the FBI were all willing to see the potential for good in Jesse at a time when he was struggling to find his new path in life. Even after relapsing into drugs, these individuals were still willing to give him a chance to make amends. These stories are all too rare in the U.S. justice system, but Jesse’s serves as a powerful reminder that even those who are deeply broken are not irredeemable, and they may even be capable of rendering great good out of their pain and brokenness.

You can watch Jesse Morton discuss his story and these issues with ICSVE Director Anne Speckhard here.

Reference for this article: Speckhard, Anne and Ellenberg, Molly (August 25, 2020). Jesse Morton: A Story of Trauma and Radicalization. Homeland Security Today

About the authors:

Anne Speckhard, Ph.D., is Director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE) and serves as an Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Georgetown University School of Medicine. She has interviewed over 700 terrorists, their family members and supporters in various parts of the world including in Western Europe, the Balkans, Central Asia, the Former Soviet Union and the Middle East. In the past five years years, she has interviewed 245 ISIS defectors, returnees and prisoners as well as 16 al Shabaab cadres and their family members (n=25) as well as ideologues (n=2), studying their trajectories into and out of terrorism, their experiences inside ISIS (and al Shabaab), as well as developing the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project materials from these interviews which includes over 200 short counter narrative videos of terrorists denouncing their groups as un-Islamic, corrupt and brutal which have been used in over 150 Facebook and Instagram campaigns globally. She has also been training key stakeholders in law enforcement, intelligence, educators, and other countering violent extremism professionals, both locally and internationally, on the psychology of terrorism, the use of counter-narrative messaging materials produced by ICSVE as well as studying the use of children as violent actors by groups such as ISIS. Dr. Speckhard has given consultations and police trainings to U.S., German, UK, Dutch, Austrian, Swiss, Belgian, Danish, Iraqi, Jordanian and Thai national police and security officials, among others, as well as trainings to elite hostage negotiation teams. She also consults to foreign governments on issues of terrorist prevention and interventions and repatriation and rehabilitation of ISIS foreign fighters, wives and children. In 2007, she was responsible for designing the psychological and Islamic challenge aspects of the Detainee Rehabilitation Program in Iraq to be applied to 20,000 + detainees and 800 juveniles. She is a sought after counterterrorism expert and has consulted to NATO, OSCE, the EU Commission and EU Parliament, European and other foreign governments and to the U.S. Senate & House, Departments of State, Defense, Justice, Homeland Security, Health & Human Services, CIA, and FBI and appeared on CNN, BBC, NPR, Fox News, MSNBC, CTV, CBC and in Time, The New York Times, The Washington Post, London Times and many other publications. She regularly writes a column for Homeland Security Today and speaks and publishes on the topics of the psychology of radicalization and terrorism and is the author of several books, including Talking to Terrorists, Bride of ISIS, Undercover Jihadi and ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Her publications are found here: https://georgetown.academia.edu/AnneSpeckhardWebsite: and on the ICSVE website http://www.icsve.org

Follow @AnneSpeckhard

Molly Ellenberg, M.A. is a research fellow at ICSVE. Molly Ellenberg holds an M.A. in Forensic Psychology from The George Washington University and a B.S. in Psychology with a Specialization in Clinical Psychology from UC San Diego. At ICSVE, she is working on coding and analyzing the data from ICSVE’s qualitative research interviews of ISIS and al Shabaab terrorists, running Facebook campaigns to disrupt ISIS’s and al Shabaab’s online and face-to-face recruitment, and developing and giving trainings for use with the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project videos. Molly has presented original research at the International Summit on Violence, Abuse, and Trauma and UC San Diego Research Conferences. Her research has also been published in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, the Journal of Strategic Security, the Journal of Human Security, and the International Studies Journal. Her previous research experiences include positions at Stanford University, UC San Diego, and the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland.