Mona Thakkar & Anne Speckhard Despite notable repatriation progress in early 2023, involving 14 countries…

How Men and Women Were Drawn to the Hyper-Gendered ISIS Caliphate

Anne Speckhard and Molly Ellenberg

As published in Homeland Security Today:

At the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism [ICSVE], we have explored the implications of repatriating foreign terrorist fighters [FTFs] through the lenses of ISIS children, women, and fighters. We have examined cases of individuals who have spontaneously deradicalized – that is, become disillusioned with ISIS and its ideology as a result of negative experiences in the group, dashed expectations, and reflection while incarcerated, as well as cases of returnees who fell back into ISIS after serving time in prison as well as those who wished to return to the group after defecting and escaping from it. We have studied the vulnerabilities, motivations, influences, experiences, and sources of disillusionment of ISIS members, all of which will come into play when assessing risk and implementing rehabilitation and reintegration programs for returning FTFs.[1]

Our most recent study explores the impact of gender on the many aspects of individuals’ trajectories into and back out of ISIS as well as inside the group. The reasons for studying the roles of gender in ISIS are many, including how ISIS divided roles and responsibilities in the group by gender, insisted upon gender conforming behaviors and dress, empowered men and women in specific manners while also disempowering women vis a vis men, and how they also used gender stereotypes and conservative Islamic ideals about modesty and familial roles to attract both men and women into the group.

The literature on ISIS women addresses many aspects of their involvement in the group, including their motivations for joining and travel, their treatment inside ISIS, as well as attempts to understand the various roles they took and continue to take now while held prisoner in Syrian detention camps. At least 10 percent of all FTFs who traveled from outside of Iraq and Syria to Syria are estimated to have been women, and from some countries these numbers rose to between 30 to 40 percent females. For instance, 36 percent of FTFs from France and up to 40 percent of FTFs from the Netherlands were women. Outside of Europe, about 12 percent of Tunisian FTFs, 15 percent of Australian FTFs, and 17 percent of Moroccan FTFs were women.[2] Far more females joined ISIS than any other militant jihadist terrorist group because ISIS was not only interested in recruiting male fighters but was also interested in state-building. This latter aspect necessitated recruiting women as wives for these fighters and to ensure the next generation of fighters would also be born and raised in the ISIS Caliphate. ISIS women primarily acted as wives and mothers but were also used in various roles from couriers, online recruiters, teachers and medical professionals, some took on limited fighting roles including snipers and suicide bombers, and they also enforced ISIS’s strict morality code as members of the al Khansaa brigade of the hisbah. There has also been quite a bit of research on “jihadi brides,” women who followed their men into ISIS or who were seduced by ISIS recruiters online and traveled to join them in the Caliphate.[3] These contrasting images of brutal enforcers, propagandists and fighters deeply entrenched in ISIS’s ideology with more the more passive roles of female followers demonstrate the spectrum of female motivations for joining, personal agency involved and ideological indoctrination and actual involvement in violence, and reinforces the mistake of viewing women’s reasons for joining and involvement in the group monolithically in discussions of repatriation of ISIS women and children. Likewise, in some cases ISIS women were as cruel and violent, or even more so, as ISIS men, and in other cases men who ended up in ISIS resisted engaging in violent actions whereas some women eagerly embraced violence and felt empowered by it. Thus, seeing gender as a default variable explaining differences between men and women is also a mistake.

It is also important to recognize that in terms of recruitment for both men and women, ISIS presented itself as a bastion of traditional gender roles, a stark contrast to the liberal democracies of the West where conservative Muslim men and women may feel alienated if not outright harassed for overt displays of religiosity, such as dressing in conservative Islamic clothing and for men growing Islamic conforming beards. Likewise conforming to strictly traditional gender stereotype and attempting to honor gender separation can be very difficult, often resulting in Islamophobic insults. Thus when ISIS offered the vision of their Islamic utopia many Muslim men and women resonated with that dream. Salma, a 22-year-old Belgian woman, recalls how she felt when her father contacted her from the Islamic State and asked her to join him: “[In Belgium], sometimes you feel targeted. You feel watched upon if you’re not the same like them. If your head is covered, you’re wearing hijab this big and everything, you’re watched upon.” Salma joined her father in the hopes of being able to live as a Muslim woman without oppression, but she soon realized the horrors of ISIS. When she attempted to escape, her father was killed in front of her.

Similarly, for those women who had histories of sexual assault and abuse, ISIS offered a vision of protection for females by enforcing strict gender separation and claiming to protect women’s honor. Forty-six-year-old Canadian Kimberly Pullman resonated to these claims as after a long history of sexual abuse she was desperate to regain her honor and feel protected by a faithful Islamic husband whom she expected to treat her with respect versus abuse. After she met an ISIS recruiter online and he gained her trust, she told him about her Kuwaiti ex-husband who had abused her and her children: “He said, ‘When me and my brothers, when we take Kuwait and we take Saudi and it’s back in actual Muslim hands,’ he said, ‘we’ll go find him and we’ll restore yours and your children’s honor.’” Kimberly recounts, “This is something I hadn’t had for a very, very long time. Giving back a purity that was taken away, I think it hit me hard.” Unfortunately, her ISIS husband was also abusive, as were the ISIS men who at one point imprisoned and raped her yet again.

While Kimberly believed that joining ISIS would restore her honor and convey upon her a pure, feminine, traditional Islamic identity that her sexual assaults in the West had denied her and Salma followed her father into ISIS believing life wearing a hijab would be easier in the Caliphate than it had been in Belgium, both were horribly disappointed. In fact, it was the desecration of these very traits, alongside the brutal violence of ISIS, that ultimately broke their trust in ISIS. Salma was kept prisoner in a squalid madhafa [guesthouse] until her father was able to get her, as women were forbidden from going anywhere alone. She was returned to the madhafa after her father was killed and ISIS imprisoned and tortured her husband for trying to escape. Kimberly was raped by ISIS prison guards after her own escape attempt. Indeed, ISIS’s mistreatment of women was a major source of disillusionment for the majority of women in ICSVE’s sample.

Just as the women hoped to establish traditional feminine identities in ISIS, many men similarly hoped that joining ISIS would allow them to feel like “real men.” They wanted to be heroes, warriors, protectors, and breadwinners, and felt prevented from establishing such identities in their home countries. In the West, Muslim men of immigrant descent who experienced marginalization and discrimination in their schools and employment felt disempowered and emasculated. Many felt humiliated by not being able to earn a living as they believed they ought. Elsewhere in the world, such as Tunisia, widespread economic crises and corruption also prevented many men from becoming employed and subsequently married. Iraqi Sunnis felt that sectarian discrimination prevented them from obtaining jobs consistent with their qualifications. In addition to the chance to be a warrior and a hero for the Syrian people, or for Iraqis to engage in a struggle to establish Sunni dominance in Iraq, ISIS offered these men jobs, cars, free housing, and arranged marriages.

Abu Bakr al Kurdi, a 26-year-old from Denmark, was recruited to join ISIS by a family member who told him, “Come over here. Everything is good. The Muslims are happy that we are here to help them. You make a jihad. It’s honor. A place to live without oppression. You can be like a hero.”

When frustrated by their circumstances, ISIS offered clear answers. Abu Ayad, a 20-year-old Iraqi would-be suicide bomber, saw ISIS’s propaganda videos on social media: “They affected me because I was poor. I wanted to improve my living condition [for] marriage. I wanted us to have a house and for me to get married, and to have money.”

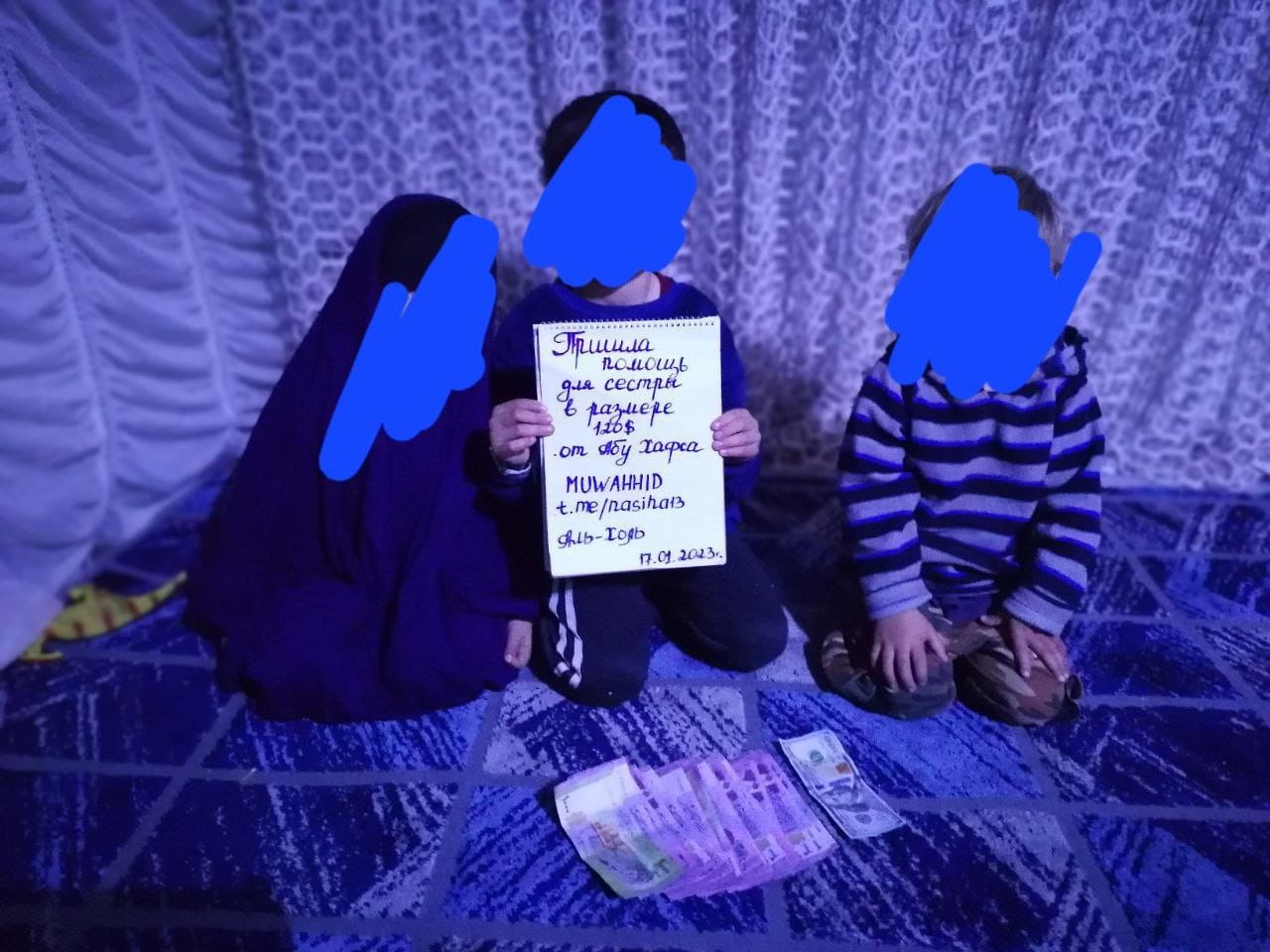

Like the women who were quickly disillusioned of any hope that they would be cherished in the Caliphate, the men who joined often also learned soon after joining that ISIS mistreated women and innocent civilians, and many FTFs also felt mistreated by ISIS, which they felt gave better pay, food, and overall treatment to Iraqi and Syrian members. Watching their wives and children starve under ISIS’s rule was a far cry from their dreams of being able to protect and provide for their families.

While the men and women found that the positive aspects of a traditional, heteronormative, gender-binary society were sorely lacking under ISIS, they also quickly learned that ISIS was eager to brutally enforce their extreme interpretations of these roles and behaviors. As mentioned briefly above and extensively in prior articles, the ISIS hisbah punished women who failed to comply with ISIS’s strict dress code or rules regarding chaperones by flogging them and using metal teeth to bite them until they bled, sometimes even to death. Women accused of adultery were often stoned, even when evidence was lacking. The morality police also punished ISIS women’s husbands for allowing any nonconforming behaviors by beating these husbands or leaving them to die while caged in frequently bombed areas.

ISIS’s misogyny was further emphasized in their blatant use of sexual violence as a means of domination. ISIS enslaved and raped Yazidi, Shia, and other women, including Sunni wives of Syrian regime soldiers. Some ISIS women, like Kimberly, were raped in ISIS prisons; many others were forced to marry and procreate with men they did not wish to marry. ISIS widows were locked up in filthy madhafas until they agreed to marry again. Likewise, ISIS, one of the wealthiest terrorist groups in history, used human trafficking as a significant source of revenue selling Yazidi women to their own cadres and to wealthy businessmen.[4] Some men in the ICSVE sample also reported experiencing or witnessing male-on-male rapes, an underreported practice that is all too common in hyper-masculine regimes that use sexual violence against both men and women to exert power and control, to humiliate, and to degrade. Regardless of the victim’s gender, sexual attraction is not part of the equation in rape, Likewise, ISIS enforced deviations from their definition of appropriate sexuality by throwing men they believed to be homosexual from rooftops.

It is clear that gender played a strong role in FTFs’ motivations for joining ISIS, their experiences living under the Caliphate, and their sources of disillusionment with the group. Addressing issues related to gender will also be important in regard to repatriation and rehabilitation. For both men and women, the stresses of trying to live a conservative Islamic life in a Western democracy will remain if and when they are repatriated and if and when they are released from prison. Discrimination and marginalization are important to address at a societal level in general, and, more practically, must be recognized as legitimate grievances in the process of helping returnees develop prosocial coping mechanisms and establish identities that are consistent with their faith and can be practiced in a liberal society. Men, especially, will need the skills to gain employment after released from prison in order to give them a sense of dignity and purpose and women may desire the same to feel independent and able to provide for their children, particularly if widowed. Both men and women have expressed deep concerns about the stigma they will likely suffer upon their return home, forever being seen as a duped ISIS bride who may be dangerous or violent ISIS fighter.

Moreover, the repatriation process must be carefully calculated. In our sample, women were highly motivated to join ISIS by a desire to keep their families safe and united. If women learn that their children are to be repatriated without them, they may be vulnerable to recruitment by new groups who promise to keep them together, along with their husbands, if they are still alive. Women in Camp Hol, Syria, escape on a weekly basis with their children, some to resurface at home, others to disappear into Idlib, Syria, or Turkey, perhaps to rejoin ISIS or other militant jihadist groups. Furthermore, prior trauma was a significant vulnerability for women who joined ISIS, and their traumas have been multiplied and compounded during their time in ISIS as well as in the detention camps. Thus, the longer the women remain in the camps, the more vulnerable they become to recruitment by new groups. Likewise, most men who we interviewed have experienced extreme trauma in their time in ISIS and in prison. Both will need effective posttraumatic stress counseling to be a major part of whatever rehabilitation program is instituted upon repatriation. All of these factors make it abundantly evident that the gender perspective must be kept in mind not only in considering the experiences of women, but in considering how and why both men and women were drawn into ISIS, their gendered experiences inside the group, how and why they left (if they did), and how their risk of recidivism can be minimized.

Reference for this article: Speckhard, Anne and Ellenberg, Molly (August 31, 2020). How Men and Women Were Drawn to the Hyper-Gendered ISIS Caliphate. Homeland Security Today

About the authors:

Anne Speckhard, Ph.D., is Director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE) and serves as an Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Georgetown University School of Medicine. She has interviewed over 700 terrorists, their family members and supporters in various parts of the world including in Western Europe, the Balkans, Central Asia, the Former Soviet Union and the Middle East. In the past five years years, she has interviewed 245 ISIS defectors, returnees and prisoners as well as 16 al Shabaab cadres and their family members (n=25) as well as ideologues (n=2), studying their trajectories into and out of terrorism, their experiences inside ISIS (and al Shabaab), as well as developing the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project materials from these interviews which includes over 200 short counter narrative videos of terrorists denouncing their groups as un-Islamic, corrupt and brutal which have been used in over 150 Facebook and Instagram campaigns globally. She has also been training key stakeholders in law enforcement, intelligence, educators, and other countering violent extremism professionals, both locally and internationally, on the psychology of terrorism, the use of counter-narrative messaging materials produced by ICSVE as well as studying the use of children as violent actors by groups such as ISIS. Dr. Speckhard has given consultations and police trainings to U.S., German, UK, Dutch, Austrian, Swiss, Belgian, Danish, Iraqi, Jordanian and Thai national police and security officials, among others, as well as trainings to elite hostage negotiation teams. She also consults to foreign governments on issues of terrorist prevention and interventions and repatriation and rehabilitation of ISIS foreign fighters, wives and children. In 2007, she was responsible for designing the psychological and Islamic challenge aspects of the Detainee Rehabilitation Program in Iraq to be applied to 20,000 + detainees and 800 juveniles. She is a sought after counterterrorism expert and has consulted to NATO, OSCE, the EU Commission and EU Parliament, European and other foreign governments and to the U.S. Senate & House, Departments of State, Defense, Justice, Homeland Security, Health & Human Services, CIA, and FBI and appeared on CNN, BBC, NPR, Fox News, MSNBC, CTV, CBC and in Time, The New York Times, The Washington Post, London Times and many other publications. She regularly writes a column for Homeland Security Today and speaks and publishes on the topics of the psychology of radicalization and terrorism and is the author of several books, including Talking to Terrorists, Bride of ISIS, Undercover Jihadi and ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Her publications are found here: https://georgetown.academia.edu/AnneSpeckhardWebsite: and on the ICSVE website http://www.icsve.org

Follow @AnneSpeckhard

Molly Ellenberg, M.A. is a research fellow at ICSVE. Molly is a doctoral student at the University of Maryland. She holds an M.A. in Forensic Psychology from The George Washington University and a B.S. in Psychology with a Specialization in Clinical Psychology from UC San Diego. At ICSVE, she is working on coding and analyzing the data from ICSVE’s qualitative research interviews of ISIS and al Shabaab terrorists, running Facebook campaigns to disrupt ISIS’s and al Shabaab’s online and face-to-face recruitment, and developing and giving trainings for use with the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project videos. Molly has presented original research at the International Summit on Violence, Abuse, and Trauma and UC San Diego Research Conferences. Her research has also been published in the Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, the Journal of Strategic Security, the Journal of Human Security, and the International Studies Journal. Her previous research experiences include positions at Stanford University, UC San Diego, and the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland.

[1] Speckhard, A., & Ellenberg, M. D. (2020). ISIS in Their Own Words. Journal of Strategic Security, 13(1), 82-127.

[2] Mehra, T. (2016). Foreign terrorist fighters: Trends, dynamics and policy responses. International Centre for Counter-Terrorism..

[3] Martini, A. (2018). Making women terrorists into “Jihadi brides”: an analysis of media narratives on women joining ISIS. Critical Studies on Terrorism, 11(3), 458-477.

[4] Levitt, M. (2014). Terrorist financing and the Islamic state. testimony submitted to the House Committee on Financial Services, 13.