Mona Thakkar and Anne Speckhard As published in Homeland Security Today The February 2023 UN…

The Runaway Bride of ISIS: Transformation a Young Girl with a Dream to a Lethal ISIS Enforcer

by Anne Speckhard, Ph.D. & Ahmet S. Yayla, Ph.D.

The baby boy, not more than a year old, fusses in the arms of Abu Said, our Syrian fixer as the black veiled Umm Rashid seated next to him talks to us about her life in ISIS. It’s May 10, 2016 and both Abu Said and Umm Rashid are former ISIS defector, having escaped and made their way into Turkey. Umm Rashid met Abu Said, who has become our fixer for ISIS interviews in Turkey. There, he talked her into agreeing to give us this interview.

Ahmet S. Yayla and I are conducting our interview long-distance as Ahmet has fled Turkey after being threatened by ISIS and is now living in Washington, D.C.[1] While previously, Ahmet was physically present for our interviews of the Syrian defectors we spoke to in Sanliurfa, Turkey, his research associate, Murat, is now sitting in the room asking our questions as we listen in, and pose them over Skype. Abu Said translates for us. It’s awkward, but we’ve learned to live with it. We are gathered next to the computer screen listening carefully, as we interview this last of the 32 Syrian ISIS defectors fled to Turkey that we’ve managed to convince to talk to us about their time in ISIS.[2]

“I’m from Raqqa,” Umm Rashid states as her one-year-old baby in her arm cries. She bumps him up and down trying to get him to settle. “I was born in 1995. I’m 21-years-old, from a family of four. I have a younger sister,” she explains in response to our questions about how she grew up. “My father was crippled, so my mother worked to feed the family. We are farmers. Also, my mother cleaned the schools.”

“My father fell down from a construction site and got crippled,” she explains. “I never saw him walking. When I was little, I would stay with my father at home. My mother would be out working all the time. I never saw her a lot. But my mother loved us really a lot.” As she speaks I imagine her mother’s hard life, trying to make ends meet without a provider, juggling jobs between farming and the hard work of cleaning schools.

“When the [Syrian] war started, our region was also affected. My mother was scared and told me, ‘Oh my daughter, I need to get you married!’ When the [Syrian] regime left Raqqa Ahrār ash-Shām acquired Raqqa and things went crazy,” Umm Rashid sadly explains referring to one of the militias that rose up to fight Assad. “We heard that the rebel militias were taking girls and forcing them to get married to their soldiers.”

But as a teenager, Umm Rashid had a dream. She wanted to be a doctor. Up to then her parents had been behind it, despite their conservative Syrian background. But with the Syrian uprising and local militias forcing young girls into marriage she wasn’t safe as a single girl anymore. “So, my mother told me I need to get married.”

“Because of the war, I dropped out of school at ninth grade. I wanted to be a doctor,” Umm Rashid explains. Despite not being able to understand her Arabic, it’s clear her voice is filled with intelligence.

“After things got bad in Raqqa, I needed to get married. I loved our neighbor’s son. My neighbors had asked for me to marry, but we refused because I wanted to study. But when things got bad, my family said we need to accept to get married to this guy.” So her dream to be a doctor vanished in the smoke of militias rising up across Syria.

“When the regime left Raqqa, I couldn’t take the final exams of the ninth grade,” Umm Rashid explains going back to how she tried hard to make her dream come true. Because the regime people left Raqqa, I had to go somewhere to take it where the regime was. I did travel and I passed it. Of course we were so poor; people used to find teachers to have their children get private lessons but since we didn’t have money we couldn’t hire private teachers. But I passed the exams anyways without them. My sister was one year behind.”

As she talks I imagine this now veiled in black woman, as the 17-year-old girl she was only a few years ago, getting her family behind her as she defied Syrian village traditions of marrying young. I imagine her studying without any advantages and even traveling during wartime to pass her exams. As I reflect on her drive and courage, I think to myself: Perhaps I should give her some money when we finish this interview. She is obviously smart. All her dreams were killed by the Syrian revolution and ISIS. Maybe I can help pay for her to take language lessons here in Turkey—it would be a good thing to do…As a woman I admire her spunk and tenacity to hang on to her dream.

As I muse the connection breaks and Ahmet receives a WhatsApp message from Abu Said saying Umm Rashid took advantage of it to quickly nurse her fussing baby. Abu Said sends a photo from earlier in the interview, when Umm Rashid let him hold the baby. The child is a cute dark-haired little guy who brings a smile to our faces and helps place us in the room with them.

When we reconnect, Umm Rashid continues her tragic story. “My mother was making 3 to 5 thousand suris per month [approximately100 dollars per month] and we were using some of that money for medications for my father as well.” As a youngster, Umm Rashid and her sister, were so poor she and her sister couldn’t buy any of the normal childhood treats. “Our friends used to purchase donar kebab meat from the shops on the way to school. We would look at them, but we couldn’t purchase anything. We brought only tomato paste and bread with us from home.”

“When the regime left because of the rebellion, the ninth-grade exams were canceled. I had to go to Hama for the exams. I passed the 9th grade exam,” Umm Rashid tells us proudly. “But my mother looked and the situation was so bad. She decided I needed to get married. She told me anyone who wants to get married to you: I have to consider that.”

I imagine this mother and daughter’s disappointment—the mother having had her own life energy sapped from her with her husband becoming crippled, and all the family financial responsibilities falling on her shoulders. It must have been hard having to tell her precocious teenage daughter to give up her dream to become a doctor—to instead marry young and become the servant of her in-laws.

“I got married with our neighbor’s son,” Umm Rashid continues, her voice flat and devoid of emotion. “My husband’s mother talked to my mother and they arranged it.” But despite liking the neighbor’s son, he was not the eldest and things did not go well for young Umm Rashid. “My husband had four siblings, three sisters and one brother. I was so young. I didn’t know anything. My husband was the middle child so he didn’t have a say to what was going on at home. Their father was deceased. My husband’s sisters started to behave toward me very badly. My mother-in-law beat me.”

“I was thinking about my options,” Umm Rashid explains. As her own family was impoverished and economics in the region were worsening; divorce carries stigma in Syria; and being single and young was dangerous—given the militias in the region, Umm Rashid had few choices open to her. “I decided my mother’s home wasn’t better than what was here. My husband was here. I decided I needed to bear it. My husband’s name was Yusuf. He was called Abu Hamid.”[1]

“‘You have to be patient,’ my mother told me. “If you come to us, you are going to suffer from hunger. At least over there you have something to eat.’ So, I stayed there with my husband for six months. After six months, one day my husband fled. I don’t know why he fled. I know that his family was not behaving well toward him. Even his older brothers were beating him up as well. Soon we found out that Ali was in Tell Abyat and he was working in Tell Abyat. I continued with my husband’s family. Soon I learned that Ali had joined Jabhat al Nusra.”

At the time that Umm Rashid is referring to, the rebel group of Jabhat al-Nusra was becoming the umbrella organization of the ragtag groups of villagers who had taken up arms against the regime. Jihadi ideologues from Jordan and elsewhere had flooded into Syria, preaching the concepts of “martyrdom” and militant jihad as they organized and affiliated al-Nusra to al-Qaeda.

“First I was thinking, alhamdulillah [praise to Allah], Ali found a job and was working. I didn’t know what Jabhat al-Nusra was and I was happy that he had a job. Then the militias in Raqqa got mixed again, and the groups started to fight each other.” Umm Rashid is referring to the battles that began between ISIS and Jabhat al Nusra as ISIS tried to take control of Raqqa and the surrounding regions.

“Just before this happened, my husband came back. When he came back he had money. He bought gold for me. He had a car. He was distributing money to all his family. He stayed one week with me and then he left. Then I heard that the ‘brothers’ came. The ‘brothers’ were ISIS. Meanwhile the groups were fighting each other and I had not heard from my husband. One day I learned that he was wounded and soon after that he died. He became a ‘martyr.’

After he died, my mother-in-law took everything from me, even my clothes and told me to go to my mother’s home. She told me, ‘Because of you, my son died. You brought bad luck to us.’ My mother-in-law loved money.”

“You didn’t have a child from him?” we ask Umm Rashid through Abu Said, who is sitting in the room with her.

“No, I was not with him that much because there were so many people inside the house,” Umm Rashid answers sorrowfully. “I went back to my mother’s house. I waited my iddah,” she explains, referring to the mandatory three months waiting period for widows to determine if they are pregnant or not. Reflecting back on her marriage to Yusuf, she explains, “We weren’t happily married. There was always conflict in the house. My mother-in-law didn’t allow me to sleep with my husband, so I didn’t experience a real marriage. There were three rooms in the house, but four other siblings, so we were not given a room.”

Her story just gets worse. “During the fight in Raqqa, a mortar came down on our home. My mother and father died, my sister was wounded.” This was 2014. Umm Rashid was just 17, all her dreams destroyed by war.

“My sister was wounded in her hand, so her arm was amputated. We were alone at home. Our neighbor, a woman, was trying to help us. For example when there was aid from different groups they would drop a box in front of our door. If that woman had something to feed us she would give us meals. We were suffering and had nothing. That woman was from al-Khansaa, from ISIS.

Al-Khansaa was formed in 2014 in Raqqa as the female arm of the ISIS morality police, or hisbah, to placate the locals who were getting riled up about men arresting or punishing their women for dress code and other morality infringements. To calm them women were enrolled as morality police as well.[3]

“One day,” Umm Rashid continues, speaking of her neighbor in the hisbah. “She came and said, ‘Why don’t you get married to an emir from ISIS? I can arrange that.’ Her name was Umm al-Khattab.”

“Of course, I was out of my iddah [mandatory waiting time for remarriage] for two months. Our entire house was demolished except for one room. We [she and her sister] were living in that room. Umm al-Khattab got me married to a Saudi emir. His name was Abdullah al Jazwari.”

“He was a really nice man, he was like a gentleman and he behaved so nicely to me. He also accepted my sister to live with us. So my sister came also. We lived together like this. I was happy with him. He was behaving toward me really well. He was an emir.”

“After two months, he asked me why don’t you join al-Khansaa? He was forty-years-old. I didn’t know much about him. We never talked about ourselves much. I knew he was my husband, but that was it. He used to come home for his meals. I cleaned his clothes and I treated him really well because he was behaving toward me really nicely, but I didn’t know much about him.”

“From one side Abu Abdulla (her husband) and Umm al-Khattab were talking to me about joining al-Khansaa. Basically they were encouraging me to serve for the religion. The reason I accepted is that my mother and father were killed by an Alliance [Coalition] mortar during the first clashes. So, I accepted to become a member of al-Khansaa.” This was the turning point for Umm Rashid. Her parents killed accidentally by the Coalition bombings she decided to side with and serve their enemy—ISIS.

“Because my husband was an emir, I was not sent to the training camp,” Umm Rashid explains. While the group regularly publishes pictures of women holding weapons in supposed training exercises we’ve most often heard of women working in various jobs, but not having to take ISIS’s weapons or sharia training. Of the 63 ISIS cadres—prisoners, returnees and defectors—ICSVE have thus far interviewed, many tell us that men go for sharia training, but the women are instructed individually at home, by their husbands. Likewise, Western soldiers mock the way the ISIS women are holding their rifles in ISIS propaganda photos, making it clear that they are purely for propaganda purposes and not likely showing actual training.

“There were a lot of fourteen and fifteen-year-old girls in al-Khansaa,” Umm Rashid adds. She was seventeen at the time. “When I first registered, Umm al-Khattab helped me a lot. They gave me a weapon. I joined her brigade. Umm al-Khattab was the emir of that brigade,” Umm Rashid explains. As we’ve heard from the 63 ISIS cadres (defectors, returnees and prisoners) ICSVE has interviewed, the women who join the hisbah are armed with a Kalashnikov and have broad powers over the civilian population—able to fine, punish and arrest them for any type of morality offenses. They have an exalted status over civilians and answer to practically no one.

“Umm al-Khattab was not the emir of all of al-Khansaa, but of this brigade. I knew her for a long time because she was our neighbor. From the start, I knew how to work in the brigade because Umm al-Khattab was talking to me all the time.”

“Abu Abdullah would bring dinner from out because I was working, or we would eat out at work,” Umm Rashid explains about her domestic life and work and home life balance. “My husband would come home early sometimes so I would go home early. It depended on me. I could go home early or not.”

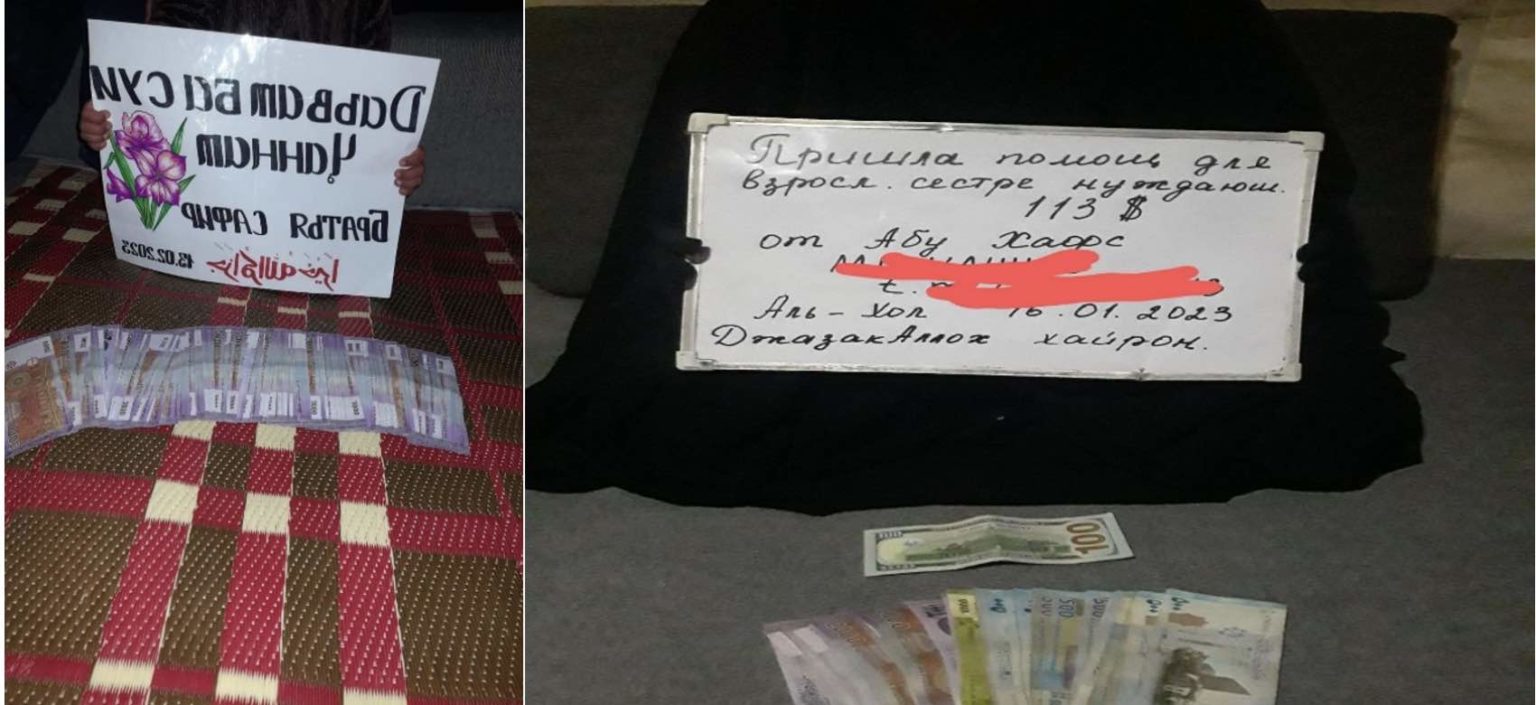

“Umm al-Khattab would come and pick me up in a van, our brigade worked in that van with six or seven other women. We were in charge of the market place. Because I was so poor in the past, I was trying to be generous to other poor people. Abu Abdullah was so generous with me. He would give me a lot of money to me. I was not used to having money. I would save it and give some to my sister and also gave money to the poor people. I was happy he was giving it so generously.”

As I listen to Umm Rashid, picking up on her obvious intellect and hearing this kindness, I wonder if it’s possible to give her some money, through Abu Said, as a gift to help her take language lessons in Turkey and perhaps pick back up on her dreams of becoming a doctor. My mind drifts to how I could arrange that as she continues.

“The van would drop us off at the Tell Abyat market in Raqqa each day. Our job was to check the market on our regulations. For example we would check abayas if they are too tight or too transparent.”

Thrilled to be hearing not just about, but from an actual member of the ISIS hisbah, we ask Umm Rashid to explain to us how women are punished. We know the men have their shirts removed and are flogged in public, “But what about the women?” we ask wondering how ISIS handles this delicate matter. “Are they undressed as well, and if so where?”

“For example if there is a woman with a colored abaya, we would arrest the husband and wife and take them to the hisbah jail. They would take the woman to the female’s hisbah and the man to the male’s hisbah,” Umm Rashid answers. Later we will compile a complete description based on our ICSVE interviews of ISIS cadres and Syrian civilian prisoners who describe the horrific conditions and torture practices inside these prisons.[4]

“We would take off the clothes of the woman until she is in her underwear. Then we would beat her with a lash. Then there are special women in the hisbah for biting,” Umm Rashid states as our ears perk up. We have heard about this practice of biting women but have never had a firsthand account.[5] “They would bite that woman. So, we would torture that woman so badly, that when the husband came from the other side she wouldn’t be able to walk. Then from out of this prison, she would feel I would never do this again, because of the things she suffered from the imprisonment. Her husband needed to pay a fine and he needed to purchase the proper abaya and sign the paperwork that he would comply to the rules completely in the future. If the woman repeats her offense, we would take the husband and put him in a football field where Coalition forces used to bomb a lot. We had a prison and we would put him in that prison. Most of the time he would die of fear because of the explosions in that field.”

My head reels as I feel myself recoiling in horror. She sounded so intelligent and so driven to become something good—but here she is telling us this horror in which she willingly participated.

“You must have felt really bad doing that?” I ask lamely, unable to take the horror in.

“No! It made me strong. I used to be afraid of spiders. I’m no longer afraid,” Umm Rashid explains matter-of-factly, as I imagine what we’ve heard described before by the men—women bitten with metal teeth on their breasts and fleshy parts, sometimes so badly that they bled to death.

They made her into a monster! I realize, gasping for air and glad to be separated by an ocean from her. I wanted to help her but she’s lost her humanity!

“I would do the same thing again if given the opportunity,” Umm Rashid continues. “I escaped because I have a small child. I want to go back after the baby is grown.” She wants to go back? I ask myself. She’s not a defector at all! What is she doing here endangering Abu Said and Murat? Ahmet already had to flee Turkey as a result of this project.

“They are seducing young men with those colorful abayas [traditional long dresses],” Umm Rashid says with derision in her voice. “We would also imprison and beat the woman who wore eye shadow. We behaved nicer to the women from the villages because they were poor and their abayas were torn, but the women from the city we would be very harsh on them. Ten-year-old girls were arrested if they didn’t have abayas. We forced girls to put on abayas after the age of seven.”

“Normally women are not allowed out without their marhams [male chaperones], they must be with their husband, brother or father,” Umm Rashid continues. “So if we see young people, a man and woman walking together, we would ask for their marriage license and IDs to make sure it’s their marham. We were trying to ensure that no one was out without marhams and no lovers wandering about. Men would receive at least twice the punishment we were employing on the women.”

“We would imprison women in the cemetery with skeletons, in a cage in the middle of the cemetery as a punishment,” Umm Rashid states flatly. “Most of the time when we went back to the cage in the morning, the woman was crazy.” This echoes reports we will later get from Syrian civilian prisoners about the hisbah placing severed heads of family members inside cages with imprisoned women, making them crazy with fear and grief.[6]

“We would lash forty times at once as a punishment. If the woman doesn’t know Islam she would stay in prison to learn Islam, it was a training camp of sorts.” Again, she echoes what we later hear from other prisoners, that the ISIS prisons are also used to indoctrinate and coerce those arrested into joining the group.[7]

“We went to Masur neighborhood. Once we saw a woman and man at night at ten p.m. We stopped them and they said, ‘We are married.’ Soon we realized they were not married. They were engaged. We did not release them. They got married in the prison after the fine and punishments. They got married and then we released them. Being engaged is not enough.”

“During the wedding ceremonies they make clapping with their hands. But, if there is entertainment at the wedding we would arrest the bride and groom and they would stay in prison. Then we would let them go after awhile. Entertainment at weddings under ISIS was not allowed.”

“We charged around one thousand dollars in fines per day,” Umm Rashid explains noting a not insignificant source of ISIS revenues, particularly now that their ability to sell oil has been degraded. “No one can say anything to us. If they protest about paying the fine, we arrest them. We were so powerful. No one could say anything against our decisions,” Umm Rashid declares.

I begin to understand her psychology. This girl who had dreamed of becoming a doctor had all her power taken from her. She was forced into three marriages and widowed three times. Her parents were killed in an airstrike. Her sister lost her arm. Her home was destroyed. Her in-laws treated her as their personal slave. Finally, so broken down she was happy to marry into ISIS—to be able to eat. And at that point she was given power inside a brutal organization that defines life in black and white terms, and death in battle as “martyrdom”. Aligning with ISIS she might also be able to revenge on the Coalition whose bombardments had killed her parents. And she could become strong—abandoning her childhood fears and grief. With ISIS, she was empowered, with a Kalashnikov and a title—the ISIS hisbah—the dreaded enforcers.

Umm Rashid turns to telling us about how her second husband was killed. “On the 23rd of February [2014] there was a Coalition air strike in our neighborhood. My husband was there and he got ‘martyred’ in that attack. That was in 2014. We had been married for eight months. In those eight months I couldn’t get pregnant. I went to see doctors. They said I was okay, nothing wrong with me. So maybe something was wrong with Abu Abdullah. Abu Abdullah would not talk about himself, his family, or his background. He never mentioned about his previous life to me. He provided everything for me, but I was not allowed to ask about him.”

“I could purchase anything in the market, but I could not ask about him,” she explains and then turns to the dark side of the man she married without really knowing who he was or anything about him. “He told me, ‘If you do something wrong and if there is a decision from ISIS that you should be killed, instead of ISIS I will cut your throat. So be careful.’”

“They brought his corpse to my home so I could see him one more time,” Umm Rashid recalls of when he was killed. Despite his dreadful threats, she recounts, “He was a very kind man. I had the best part of my life during my marriage to him.”

We ask about what happens to ISIS widows as we’ve heard various things from the ISIS cadres we have interviewed. Some tell us that ISIS has a system of paying widow’s benefits and that women from the hisbah regularly check in on widows and bring them food and money. But in Kosovo we interviewed a defector who told us those benefits are only paid for a short time and then the ISIS widows, unable to leave their homes on their own become so impoverished and hungry that they can easily be coerced into remarriage with the next ISIS cadre.

“ISIS had a place like a farm,” Umm Rashid explains. “So, a woman who did not have marhams [chaperones] used to live there. I stayed in the farm for my iddah.”

“Can you tell us about the biting?” we ask, finally recovered enough to inquire about this horrific practice of using metal teeth to torture other women.

“They use artificial teeth and bite the women with these. We did it, and we were correct,” Umm Rashid states without any trace of remorse in her voice. “Anyone who wants to bite can do it. I also used to bite. It is like an artificial tool. We can bite any part of the body—her back, shoulders, breasts—from the places you can’t see from the outside, and where there is ample meat. Hisbah members used to do this.”

They asked us to do that, so we have courage. For example, I used to be scared of bugs, but now I am not afraid,” she repeats. “I can beat three, four women at once. I have courage and strength now. Of course, we would tie the woman’s hands and feet.”

We ask Umm Rashid about her status in ISIS and if she was considered a foreign fighter due to her husband being from Saudi and also an ISIS emir. She doesn’t seem to understand the question answering, “There were a lot of Iraqi women. They were getting them married to the mujareen [foreign fighters]. I went to the camps and I saw them but I did not stay there,” Umm Rashid explains.

“I remembered my first mother-in-law while I was talking now,” Umm Rashid admits, opening a brief moment of vulnerability. “And I question myself. Am I really that bad luck?” Umm Rashid’s first mother-in-law blamed her for her son’s death fighting with al-Nusra and apparently the blame still haunts her. “After my iddah, after Abu Abdullah I went to see an [ISIS] doctor. The doctor was a woman of course. I asked her why I didn’t have a child and she told me that I was okay.”

Like other ISIS widows, Umm Rashid was going to soon learn her fate concerning remarriage. “Abu Abdullah told Abu Saif, his friend, ‘If I die, you get married to my wife.’ Abu Saif told me this saying, ‘If you don’t believe me that Abu Abdullah told me this, you can ask Umm al-Khattab.’ I asked Umm al-Khattab and she said, ‘Yes, I know he said this.’” So Umm Rashid was passed to the third man in the space of two years.

“Abu Saif was Tunisian. I got married to Abu Saif and in two months I got pregnant,” Umm Rashid explains her voice suddenly sounding triumphant. ISIS women are after all expected to bear children. “I got married to Abu Saif after my iddah was completed. I wasn’t thinking to get married because my first mother-in-law told me that I am bad luck and who ever I marry, dies. She even came to me after my second husband died and said, ‘Look you are bad luck, your husband died again.’ So, I wasn’t thinking to get married again. But when they told me this I decided to honor that promise.”

I try to imagine the cruelty in this young girl’s life. Yet she herself became a cruel monster in response. How the ISIS machinery works in the tragedies of the lives it overtakes.

“When she came, and said that, I wanted to talk harshly to her,” Umm Rashid recounts. “But I remembered I loved my first husband very well so because of that memory I behaved well.” Apparently she still does have a tender side, I reflect.

“I was so happy I was pregnant, and because I was pregnant I didn’t go to work. I was taking care of myself,” Umm Rashid tells us. “When Abu Saif first approached me I didn’t accept. I waited for two months but then I thought what would I do as a woman [in ISIS]? I had guarantees and protections with a man, so I got married. A sheikh came for the marriage ceremony. In front of the sheikh and two witnesses we got married.”

Abu Saif was not an emir. He was a deputy emir and an investigator. He used to work for the court as an investigator in Raqqa. He didn’t have a wife in Tunisia. Alhamdulillah, when he came to Syria he got married several times but he didn’t like those wives so he divorced them. But he loved me and I loved him.” Umm Rashid states.

Despite her overlooking his sordid past, Abu Saif’s behavior echoes many stories we heard from ISIS defectors, particularly about Tunisian ISIS members. Coming from a country with high unemployment and where they couldn’t marry unless they had prospects the Tunisian ISIS members were known to be sex starved. They stalked the local women, even sometimes accused their fathers or husbands of being with the Free Syrian Army, to cause them to give up their daughters, or the husbands to be executed to free the woman for remarriage. Or, that they married and divorced local women in a matter of days—just to use them for sex. That is the kind of man Abu Saif was.

“When he learned that I was pregnant, Abu Saif brought a maid to the home and he started to behave very well to me.”

“Was Abu Saif’s maid a slave?” we ask wondering if we will also learn how captives are treated inside the homes of ISIS cadres.

“The maid was not a slave,” Umm Rashid tells us. “He hired her with money.” In some ways I’m relieved to hear this. We already heard from Ibn Ahmed who was the guard of a facility housing 475 ISIS sex slaves who were used by foreign fighters who basically engaged in mass institutionalized rape. (Ibn Ahmed’s video interview is here.)

“Yazidi women were treated nicely,” she continues. “We were staying at the same places. They were getting married to the emirs. There were not any problems with them.” Her denial of the barbarity of ISIS is amazing, but perhaps she needs to keep all cruelties borne by her, and even those she, herself carried out, locked away in her mind to survive them.

“I stayed there for eight months while I was pregnant. Abu Saif provided me everything I wanted and made sure I was comfortable. But, as soon as I finished the seventh month of my pregnancy, the Coalition forces attacked the court in Raqqa and he got killed in that attack.”

“What do they want from us?” Umm Rashid suddenly wails, her bottled up grief and anger abruptly unleashed. Why are they attacking us? They cannot attack anywhere they want. What’s wrong with you?” Umm Rashid screams, as she gets hysterical recalling the culmination of a series of sudden traumatic bereavements.

When we try to calm her by explaining that the Coalition is trying to free the Syrian people from Assad, and the armed terrorist groups that have overtaken them—including ISIS, she continues to rant. “They are all liars!” she shouts at us, anger biting through her voice, referring to the Coalition. “They are killing Syrian people. They killed thousands of children. They are not fighting Bashar al-Assad. What they did is to kill all local Syrians and children. You haven’t seen the bodies and the corpses of boys, girls, children—babies at their mother’s breasts! The circumstances of what I have seen is so terrible” she continues, her voice filled with rage.

Hoping to calm her and keep her talking with us, we turn the conversation to her circumstances after her third husband’s death. Was she expected to marry once again?

“So, there was an invitation at the court,” she explains. “Several other civilians at the court also got killed. They [ISIS leaders] told me. ‘You are going to stay with us at the hisbah, then after you have the child we are going to get you remarried again.’ We had a discussion about that. Umm al-Khattab got married nine times and every time her husband got killed. She told me, ‘You are going to get married again.’”

We ask Umm Rashid to tell us about the marriage system in ISIS, if local women are forced into marriages. It’s a common myth in the West that Western women who join ISIS end up as sex slaves but it’s not the truth. Western women are expected to marry and ISIS even has a marriage bureau to ensure that happens. It’s local women who are abused through short marriages designed as a legitimate means of gaining sex for a short time and captive women—wives of Shia and Sunni enemies of ISIS, Yazidis and others captured by ISIS, that are forced into situations of multiple rapes or sexual slavery.

“In the hisbah we went to homes, to visit people, to see if they had marriage-age daughters. If there were girls, we would give money to the father and mother and arrange their marriages with the emirs or ISIS members,” Umm Rashid explains. “We would force their families to give up their daughters to marriage. Umm al-Khattab was known as the arranger of marriages. She would smoke,” Umm Rashid states. This is the first time we hear of actual force being used for local women to marry ISIS cadres. Everyone else has spoken of choice less choices—fathers and husbands being arrested or accused of being in the Free Syrian Army or girls seeing their families starving and knowing by marriage they can earn ISIS ration cards to feed them.[8]

That Umm al-Khattab smoked is also an indicator of the hypocrisy of ISIS. As emir of a hisbah battalion, Umm all-Khattab was responsible to arrest and brutally punish smokers—yet she smoked!

“My sister was married at the time,” Umm Rashid recounts, “an emir married her. That is emir is nice and she likes him.” In regard to her escape from ISIS, she continues, “My sister is in Iraq now. I told Umm al-Khattab, ‘I am going to go see my sister [in Iraq]. I will stay there for a week, I have not seen her for awhile.’ I was given permission. I am from al-Khansaa,” she reminds us. Given privileged status in ISIS she would be trusted to travel and return. “I lied to go to the Syrian border, to save myself from Umm al-Khattab forcing me to marry again. The reason I escaped is I didn’t want to get remarried in Raqqa and I wanted to save my baby,” she explains.

“The borders were difficult at the time so the Syrian and Turkish smugglers charged us a lot,” Umm Rashid recalls. “I was so scared I could deliver while passing the border because I didn’t know the exact date when the baby was coming. I stayed at the smuggler’s home waiting to pass the border.” Ahmet who lived near the border explains to me that many houses are located right on the Syrian and Turkish border making nighttime passage with help of one of these residents working as a smuggler, like she describes, possible. Many ISIS defectors told us of overnighting with smugglers on the Turkish border—both on their way in and again when they escaped.

“There was another woman with me who was also trying to pass. I met that woman at the border. We paid $3000 to the smuggler. We passed at two a.m. in the morning. It was so cold. I got chilled. From the border we came to Akçakale. I helped the other woman to pass. I paid for her passage as well,” Umm Rashid recounts. Again, we see a glimmer of the girl who wanted to be a doctor—to help others.

From the statistics ICSVE have been able to compile, we find that women escape ISIS far less often than men, at what we estimate to be a ratio of one to four—although the numbers are incomplete to make firm estimates.

It’s unlikely that women who have joined ISIS want to stay inside more than men do, or become less disillusioned with the corrupt, brutal and un-Islamic nature of the group. The difference in defection and return rates is far more likely that they simply don’t have the financial means to pay smugglers, are restricted in their movements inside ISIS territory, are forbidden to speak with men they don’t know, they risk rape by smugglers if they manage to hire one and they know that if they are caught they will be returned to Raqqa and forced to remarry if they are lucky, killed if they are unlucky. Rape by smugglers is no small risk. We have heard numerous stories of European women who were raped by smugglers who had complete control over these women’s lives as they made their way out of Syria or Iraq, into Turkey.

“The smuggler would not touch me because my relatives would learn and kill him,” Umm Rashid threatens when we ask about the risk of rape. “One smuggler did this in Syria. The Syrians in Turkey went to Syria and brought him out to Turkey and beat him very badly,” she explains referring to how seriously males take the honor and safety of their female relatives. “So, we were safe from him.”

“But if liked ISIS why did you leave?” Murat asks, pushing back a bit.

“Because the Coalition forces kept bombarding us. I felt I have to save my child’s life,” Umm Rashid states, although only moments ago, she also said she didn’t want to be forced into yet another marriage by the misogynist ISIS.

“For the last nine months I am in Turkey,” Umm Rashid states explaining where she now lives (information we chose not to disclose here for her safety). “I gave birth to my baby here. A Syrian midwife helped me to birth my baby at home. I stayed with my relative in xxxxx. I wanted to work because I didn’t have any money, but I couldn’t because I just delivered the baby. I stay with my uncle and live [with the baby] in a small room.”

“Do you want to get married again? What is your future?” We ask, curious to know if she will pursue her dream somehow, here in Turkey.

“I want to go back. When my son is three or four-years-old, if ISIS still exists, I will go back and fight with them,” she states creating a chill down my spine.

How could Abu Said bring her here for an interview? I think as she continues. She could have worn a bomb belt and killed everyone in the room!

“Islamic State is a really good group. I have to help them. If they allow me to keep my son, I would remarry,” she states, referring to the Islamic practice of women leaving their children from a previous marriage with their previous husband’s relatives when they remarry. In her case, her Tunisian in-laws are not present to take her son if she remarries, meaning she might be able to bring him into her new family.

“What attracts you back to Raqqa?” we ask incredulously. “There are bombings there, where here in Turkey there are no bombings!”

“They are not as bad as the people tell,” Umm Rashid states.

She is totally brainwashed, like the child Ibn Omar who we interviewed previously—a boy next in line for a suicide mission until his parents found out and forced him to escape into Turkey. (His video interview can be viewed here.) Ibn Omar told us it took him a full year to get the ISIS ideology out of his mind.[9]

“Islamic State is good,” she insists. “Women are covered over there. I want my child to be an ISIS fighter. My son must go through the way of his father, follow his path,” she states referring to her wish for her son to also become a “martyr” for ISIS—the son she is cradling in her arms as she speaks. “I wish I was a martyr as well!” she adds, her eyes glimmering with a glory she imagines in such a sickening fate.

“What do you think of their beheadings?” we ask, trying to shake some sense back into her mind—to remind her how vicious this group really is.

“They only behead people who deserve it,” Umm Rashid states firmly.

“What does anyone do to deserve beheading?” we ask, finding it hard to listen to her stubborn defense of ISIS’s savagery.

“For example we chop off the thieves’ hands,” Umm Rashid explains, her voice again sounding again like the cruel hisbah member she is. “There are different crimes that you could do to deserve beheading. If you kill someone without a reason, we kill you. For example, a man went into a home of a woman and stole her jewelry and killed her. He, of course, was beheaded—because he killed that woman.”

“But what about those who flee Daesh?” we ask using the name ISIS hates.

“Why don’t they call us Islamic State?” Umm Rashid rants in response. “They call us Daesh! We are the Islamic State, not Daesh!” she rages, anger dripping from each word. “They lie about us and create negative propaganda. For example, we killed a Jordanian pilot. Why is he bombing civilians? Of course we killed him!”

“Those Coalition forces are not killing our soldiers. But they are attacking the civilians. Everyone sees that. There are big screens all around Raqqa—the killing of that Jordanian pilot was broadcast all over Raqqa. I saw it that way,” she states, explaining ISIS’s use of flat screen televisions put up by its huge propaganda arm. Abu Firas, a media emir from Southern Baghdad, told ICSVE that ISIS films everything it does for consumption inside of ISIS as she describes, as well as for audiences outside of ISIS—to horrify us with their acts of terror. Our edited video interview of Abu Firas is here.

“Can you tell us about foreign women in ISIS?” we ask.

“I had a friend at al-Khansaa, in another brigade. There was a foreign woman in their group. Her husband was Saudi and she was European. I don’t know where from exactly. We never talked to her, only greeted each other,” Umm Rashid explains. “We cannot communicate with the Westerners.” Indeed, many of the defectors told us that without a common language they could only observe Europeans, but rarely were able to converse with them.[10]

“I got married twice with ISIS fighters. I really don’t know about them [the foreign fighters], about their families and backgrounds. In ISIS, you don’t ask questions of each other, even your husband.” Indeed, hers threatened to kill her if she stepped out of line.

“You want to become a martyr, but what about the future of ISIS?” we ask.

“Inshallah [God willing], ISIS will become the real state of the region and I will become the martyr for them,” Umm Rashid declares. “What you hear here is all lies. You think they won’t last, but if you go to Raqqa you see everyone is living peacefully there.”

“How can you become a ‘martyr’ when you have a young son to raise?” we ask.

“I can die when he’s ten,” she answers. Indeed, an ISIS emir told us that boys that age were already considered men and could be sent in bomb-rigged vehicles or with suicide belts to explode themselves at checkpoints and racing into enemy lines.[11] I’m glad she has ten years of responsibility in front of her. Maybe it will take her a year of living peacefully in Turkey to deradicalize like Ibn Omar did. Although, at this point she has already been in Turkey for nine months.

“What about child suicide bombers?” we ask, given she has said she wants her son to follow in the “martyrdom” steps of his father.

“They are martyrs,” she answers without any trace of doubt in her mind. “Martyrdom is the most important rank you can reach,” she declares, echoing the ISIS teachings.

“Do you know about ISIS’s practice of taking organs from their captives and enemies?” we ask, probing for whatever else she can tell us from firsthand knowledge and her experiences inside the group.

“When they kill them, they can take organs no problem,” she answers. This, the young girl who would have become a doctor.

We are getting signals from Abu Said that we have to wrap up the interview. Her child is starting to fuss again and she has a long journey from Sanliurfa back to where she lives. Despite knowing she’s unlikely to denounce the group as many other defectors have, we ask our standard question at the end, “Do you have any advice for Syrians and Iraqis, or even foreigners, thinking to come and join ISIS?” Usually at this point our interviewees strongly denounce the group—words that we use later in our Breaking the ISIS Brand—the ISIS Defectors Counter Narrative Project making edited video clips of the defectors denouncing ISIS, to try to disrupt ISIS’s online and face-to-face recruitment.

“I advise them to come and join ISIS,” she predictably answers. “Go, die in the path of Allah. When you die for the religion, you save yourself. I strongly advise it.

“When you go back, would you like to take others with you, back to Syria?” we ask, wondering if she is recruiting for the group during her time in Turkey. We have heard from defectors living in Turkish refugee camps that young boys, in particular, are seduced by ISIS recruiters operating in the camps to go back and die as “martyrs” in ISIS suicide bombings.[12]

“Of course, if someone wants to go I will take them. I invited a lot of women in Raqqa to become ISIS members,” she answers.

We end our interview as Abu Said prepares to help Umm Rashid and her baby get transport back to her temporary shelter in Turkey. Reflecting on her words, I realize that ISIS is capable of taking normal youth from loving homes and turning them into total and utter sadists. Perhaps it’s the traumatic bereavement—losing one’s husband and parents at age 17. Being repeatedly forced into remarriage over a space of only a few years?

As many trauma survivors do, she may have needed to numb her emotions and feel nothing. And being blamed by her mother-in-law as “bad luck” for causing the deaths of both her husbands certainly seems to have haunted Umm Rashid. There is also the total loss of control—losing her home, her parents, and her husband and suffering near starvation only to then be offered an exalted status and a paycheck. These are not small things for a girl and her sister who have no other means of survival.

We see glimmers of Umm Rashid’s humanity and generosity when she gains an ISIS salary working in the ISIS hisbah and gives much of it away and when she pays a smuggler for not only her own escape, but that of a stranger encountered along the way.

Yet, when we interviewed her, she remains totally indoctrinated and loyal to a lethal organization—advising others to join and die in its behalf, and wanting to become a “martyr” for ISIS and have her baby son do the same.

Umm Rashid survived, but in the process, ISIS turned a young girl with a dream into a monster.

About the Authors:

Anne Speckhard, Ph.D. is Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Georgetown University in the School of Medicine and Director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE) where she heads the Breaking the ISIS Brand—ISIS Defectors Counter Narrative Project. She is the author of: Talking to Terrorists, Bride of ISIS and coauthor of ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate; Undercover Jihadi; and Warrior Princess. Dr. Speckhard has interviewed nearly 500 terrorists, their family members and supporters in various parts of the world including Gaza, West Bank, Chechnya, Iraq, Jordan, Turkey and many countries in Europe in addition to 63 ISIS cadres. In 2007, she was responsible for designing the psychological and Islamic challenge aspects of the Detainee Rehabilitation Program in Iraq to be applied to 20,000 + detainees and 800 juveniles. She is a sought after counterterrorism experts and has consulted to NATO, OSCE, foreign governments and to the U.S. Senate & House, Departments of State, Defense, Justice, Homeland Security, Health & Human Services, CIA and FBI and CNN, BBC, NPR, Fox News, MSNBC, CTV, and in Time, The New York Times, The Washington Post, London Times and many other publications. Her publications are found here: https://georgetown.academia.edu/AnneSpeckhard Follow @AnneSpeckhard

Ahmet S. Yayla, Ph.D., is an adjunct professor of criminology, law, and society at George Mason University. He is also senior research fellow at the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE). He formerly served as a professor and the chair of the sociology department at Harran University in Turkey. He also served as the chief of counterterrorism and operations department of the Turkish National Police in Sanliurfa between 2010 and 2013. He is the co-author of the newly released book ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Follow @ahmetsyayla

Reference for this Article: Speckhard, Anne & Yayla, Ahmet S. (September 1, 2017) The Runaway Bride of ISIS: Transformation a Young Girl with a Dream to a Lethal ISIS Enforcer. ICSVE Research Reports–Talking to Terrorists Series. https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/the-runaway-bride-of-isis-transformation-a-young-girl-with-a-dream-to-a-lethal-isis-enforcer/

References:

[1] All names of Umm Rashid and her relatives have been changed in this article.

[1] Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. Isis Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Advances Press, LLC, 2016.

[2] For a description of many of these interviews see: Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. Isis Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Advances Press, LLC, 2016; Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. “Eyewitness Accounts from Recent Defectors from Islamic State: Why They Joined, What They Saw, Why They Quit.” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 6 (December 2015): 95-118.

[3] For a complete description of female roles in ISIS please see: Almohammad, Assad & Speckhard, Anne (April 22, 2017) The Operational Ranks and Roles of Female ISIS Operatives: From Assassins and Morality Police to Spies and Suicide Bombers. ICSVE Research Reports. https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/the-operational-ranks-and-roles-of-female-isis-operatives-from-assassins-and-morality-police-to-spies-and-suicide-bombers/

[4] see: Almohammad, Asaad, Speckhard, Anne, & Yayla, Ahmet S. (August 10, 2017) The ISIS Prison System: Its Structure, Departmental Affiliations, Processes, Conditions, and Practices of Psychological and Physical Torture, ICSVE Research Reports https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/the-isis-prison-system-its-structure-departmental-affiliations-processes-conditions-and-practices-of-psychological-and-physical-torture/

[5] See: Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. Isis Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Advances Press, LLC, 2016; Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. “Eyewitness Accounts from Recent Defectors from Islamic State: Why They Joined, What They Saw, Why They Quit.” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 6 (December 2015): 95-118.

[6] Almohammad, Assad & Speckhard, Anne (April 22, 2017) The Operational Ranks and Roles of Female ISIS Operatives: From Assassins and Morality Police to Spies and Suicide Bombers. ICSVE Research Reports. https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/the-operational-ranks-and-roles-of-female-isis-operatives-from-assassins-and-morality-police-to-spies-and-suicide-bombers/; Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. Isis Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Advances Press, LLC, 2016.

[7] Almohammad, Assad & Speckhard, Anne (April 22, 2017) The Operational Ranks and Roles of Female ISIS Operatives: From Assassins and Morality Police to Spies and Suicide Bombers. ICSVE Research Reports. https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/the-operational-ranks-and-roles-of-female-isis-operatives-from-assassins-and-morality-police-to-spies-and-suicide-bombers/; Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. Isis Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Advances Press, LLC, 2016.

[8] Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. Isis Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Advances Press, LLC, 2016.

[9] Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. Isis Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Advances Press, LLC, 2016; Speckhard, Anne. “Inside the Isis Machine Turning Children to ‘Monsters’.” The Daily Beast (August 25, 2017). http://www.thedailybeast.com/inside-the-isis-machine-turning-children-to-monsters. See also his video interview here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=pRWOsgpWFQA&list=PLqpy96DXqN-dK01K_FikteDoSxScG_OT0&index=3

[10] Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. Isis Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Advances Press, LLC, 2016; Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. “Eyewitness Accounts from Recent Defectors from Islamic State: Why They Joined, What They Saw, Why They Quit.” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 6 (December 2015): 95-118.

[11] Speckhard, Anne, and Ardian Shajkovci. “Confronting an Isis Emir: Icsve’s Breaking the Isis Brand Counter-Narrative Videos.” ICSVE Research Reports (May 29, 2017). https://www.icsve.org/research-reports/confronting-an-isis-emir-icsves-breaking-the-isis-brand-counter-narrative-videos/.

[12] Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. Isis Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Advances Press, LLC, 2016; Speckhard, Anne, and Ahmet S. Yayla. “Eyewitness Accounts from Recent Defectors from Islamic State: Why They Joined, What They Saw, Why They Quit.” Perspectives on Terrorism 9, no. 6 (December 2015): 95-118.