Mona Thakkar and Anne Speckhard As published in Homeland Security Today The February 2023 UN…

Talking Back to ISIS: Understanding, Preventing, and Remediating Militant Jihadist Propaganda and Recruitment

Anne Speckhard & Molly Ellenberg

This is a pre-publication manuscript of a chapter for Programs of Deradicalization and Rehabilitation of Convicted Terrorists, in collaboration with Al-Mesbar Center.

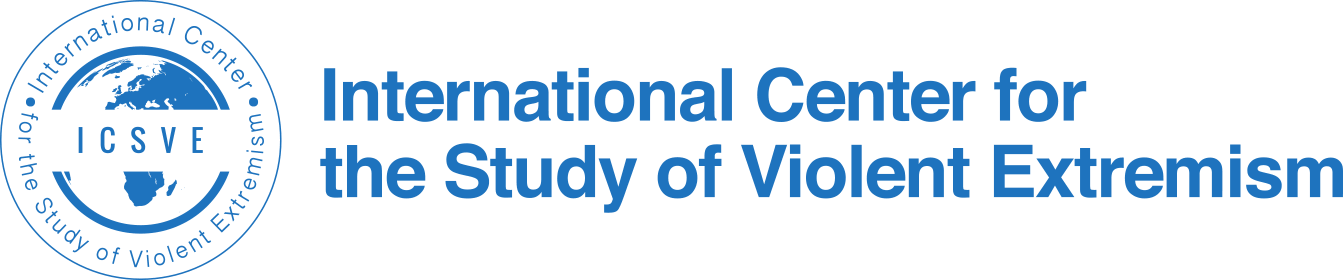

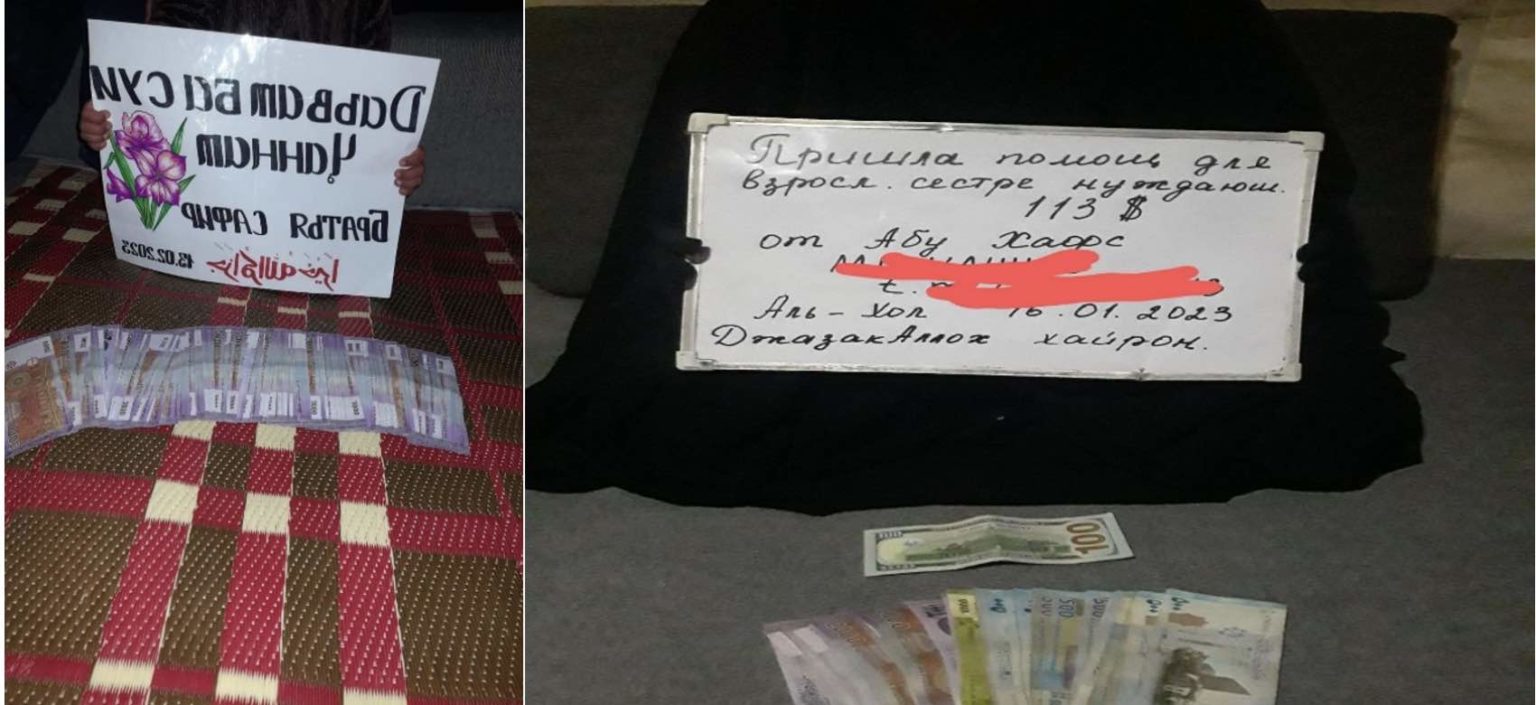

According to the United Nations and scholarly sources, approximately 30,000 to 40,000 men and women traveled to Iraq and Syria, most ultimately to live under and fight for ISIS during the height of its reign (Benmelech & Klor, 2020; Pokalova, 2019; Barrett, 2017). This flow of jihadist foreign fighters was unprecedented compared to previous conflicts in places like Afghanistan (up to 26,000 foreign fighters), the 2003 US-led coalition invasion of Iraq (up to 5,000 foreign fighters), former Yugoslavia (up to 3,000 foreign fighters), and Somalia (up to 1,500 foreign fighters) (Malet, 2015). The reason for ISIS’s successful recruitment of so many foreigners can be in part attributed to the group’s prowess on social media, though the flow of up to 60,000 non-jihadist foreign fighters in the Spanish Civil War, prior to the advent of the internet, stands as a stark exception to the rule (Malet, 2015). In both cases, however the war itself was cast as a freedom fight against a despotic dictator. During their heyday, ISIS was producing professional-quality propaganda materials including videos and digital magazines in multiple languages and posting them on both mainstream social media platforms like Facebook, Twitter, YouTube, and Instagram, as well as encrypted applications like Telegram and WhatsApp, especially once the mainstream platforms began taking down content and removing accounts posting ISIS-related materials. Even since the fall of the Caliphate, ISIS has shifted its tactical operations toward Africa and Asia but continued its global online activity, expanding to newer applications popular among young people like TikTok (Weimann & Masri, 2020). On these platforms, ISIS urges its followers to pray for the return of the Caliphate and to undertake action in pursuit of such a goal, including attacking in Coalition countries which contributed to ISIS’s demise and sending money to help break ISIS men and women out of prison in northeast Syria, a strategy reminiscent of ISIS’s early Breaking the Walls campaign which produced its original fighting force (Thakkar & Speckhard, 2022).

Therefore, it is clear that the threat posed by ISIS and the necessity to counter its radicalization and recruitment efforts has changed but not dissipated. Although preventing and countering violent extremism [P/CVE] professionals may no longer need to focus on stymieing waves of foreign fighters, it remains imperative that they continue to disrupt and refute the militant jihadist ideology which ISIS and other groups espouse and to dismantle ISIS’s ability to convince people all over the world to act in pursuit of their cause. In order to do so, those working on the ground must have a profound understanding of the motivations and vulnerabilities for becoming radicalized into militant jihadism. They must also be informed as to the highly influential effect of social media in contributing to militant jihadist radicalization and what steps can be taken to counter that effect. In the forthcoming sections, we describe two associated projects aimed at doing just that. First, we describe a psychological research project which examines the life histories and trajectories in and out of ISIS of 270 ISIS defectors, returnees, and prisoners. Then, we discuss the strategy and results of an online prevention and intervention project which disseminates counter narrative videos featuring ISIS members speaking out against the group on Facebook and other platforms. Finally, we explore how the findings of these two projects may be practically applied by P/CVE practitioners and security professionals in order to continue the important work of fighting back against ISIS’s face-to-face and online recruitment.

Breaking the ISIS Brand Research Project

The Breaking the ISIS Brand research project is an ongoing series of in-depth, semi-structured, psychological interviews conducted by Dr. Anne Speckhard, the director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism [ICSVE], with ISIS returnees, defectors, and imprisoned cadres, both men and women, from over 40 countries. The interviews began in 2015 with Syrian ISIS defectors living in Turkey and continued over the years to include Iraqis and foreigners imprisoned in Iraq, returnees to Belgium, Kosovo, Kyrgyzstan, Kenya, Denmark, and Albania, and men and women from all over the world held by the Syrian Democratic Forces [SDF] in Northeast Syria. As of 2022, the sample includes 270 interviewees.

Method (Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020a)

Interview Protocol

In all cases, the semi-structured interview started with an informed consent process followed by a brief history of the interviewee focusing on early childhood and upbringing and covering life experiences prior to becoming interested in ISIS. Demographic details were gleaned during this portion of the interview, as were vulnerabilities that may have impacted the individual’s decision to join ISIS. Questions then turned to how the individual learned about the conflicts in Syria, and about ISIS, and became interested to travel and/or join, as not all of the interviewees actually traveled to live under ISIS; a few acted as recruiters at home. Questions explored the various motivations for joining and obtained a detailed recruitment history: How the individual interacted with ISIS prior to joining, whether recruitment took place in-person or over the Internet, or both; how travel was arranged and occurred; ISIS intake procedures and experiences with other militant or terrorist groups prior to joining ISIS; and training and indoctrination. The interview then turned to the interviewee’s experiences in ISIS: Family, living and work experiences including fighting and job history; inquiry about both positive and negative aspects of the individual’s experience in ISIS; questions about disillusionment and doubts; traumatic experiences; experiences and knowledge about one’s own or others attempts to escape; being, or witnessing others, being punished or tortured; imprisonments; owning slaves; treatment of women, and marriages. The interview covered where the individual worked and lived during his or her time in ISIS and changes over time in orientation to the group and its ideology, often from highly endorsing it to wanting to leave.

In accordance with American Psychological Association [APA] guidelines and United States legal standards, a strict human subjects protocol was followed in which the researchers introduced themselves and the project, explained the goals of learning about ISIS, and that the interview would be video recorded with the additional goal of using this video-recorded material of anyone willing to denounce the group to later create short counter narratives videos. This is a project that uses insider testimonies denouncing ISIS as unIslamic, corrupt and overly brutal to disrupt ISIS’s online and face-to-face recruitment and to delegitimize the group and its ideology. The subjects were warned not to incriminate themselves and to refrain from speaking about crimes they had not already confessed to the authorities, but rather to speak about what they had witnessed inside ISIS. Likewise, subjects were told they could refuse to answer any questions, end the interview at any point, and could have their faces blurred and names changed on the counter narrative video if they agreed to it. Prisoners are considered a vulnerable population of research subjects, so careful precautions were taken to ensure that prisoners were not coerced into participating in the research and that there were no repercussions for not participating, either. The interviewer also made clear to the participants that she was not an attorney or country official and could not provide them with legal advice or assistance regarding their situation.

Risks to the subjects included being harmed by ISIS members for denouncing the group, although for those who judged it a significant risk, the researchers agreed to change their names and blur their faces and leave out identifying details. Likewise, there were risks of becoming emotionally distraught during the interview, but this was mitigated by having the interview conducted by an experienced psychologist who slowed things down and offered support when discussing emotionally fraught subjects. The rewards of participating for the subjects were primarily to protect others from undergoing a similar negative experience with ISIS and having the opportunity to sort through many of their motivations, vulnerabilities, and experiences in the group with a compassionate psychologist over the course of an hour or more. The majority of interviewees thanked the researcher for the interview.

Data Analysis

The researchers used the interviews to transcribe notes and perform a comprehensive thematic analysis. The codebook was developed using thematic analysis as described by Braun & Clarke (2006). Through open coding of the semi-structured interviews, we identified six themes: Vulnerabilities, influences, motivations, roles, experiences, and sources of disillusionment. The interviews were then coded on 342 discrete variables in SPSS Version 26. Most of the individual variables fall within these six broad categories.

Vulnerabilities including life-course variables such as experiences of different types of abuse, histories of criminality and drug use, and experiences of discrimination, hassling by police, unemployment, and poverty. Influences are divided into in-person influences to join ISIS (e.g., parents, extended family, friends, speakers, recruiters, preachers) and online influences (e.g., chatrooms, direct online contact with recruiters, passive viewing of videos or other content on different social media platforms like Facebook, YouTube, and Telegram). Motivations range from the tangible (e.g., basic needs, employment, security for one’s family), to the more humanitarian (e.g., fighting on behalf of the Syrian people or helping victims of Assad’s atrocities), to the existential (e.g., need for significance, need for belonging, desire to solidify one’s Islamic identity). Roles are coded dichotomously with regard to whether the individual held any number of specific roles in their group (e.g., fighter, preacher, recruiter, military or morality police – shurta or hisbah respectively). Experiences, too, are coded dichotomously and separated into three categories: Interviewee as victim (e.g., imprisoned by ISIS, physically or psychologically tortured, raped), interviewee as witness (e.g., witnessed execution, witnessed torture), and interviewee as perpetrator (e.g., executed people, killed others on the battlefield, owned slaves). Finally, sources of disillusionment include a wide range of reasons why people became motivated to leave ISIS, physically or psychologically, as identified in the interviews, including mistreatment of foreign fighters, mistreatment of women, and belief that the Caliphate had not been realized.

Other variables which do not fall into these six thematic categories include demographic characteristics (e.g., nationality, ethnicity, birth year, year that they joined ISIS) and ratings of radicalization on a scale from zero to three at three time points – prior to joining ISIS (assessed retrospectively), at their peak involvement in ISIS (assessed retrospectively), and at present. Variables related to remorse for their participation in ISIS, their willingness to be prosecuted, and their desire to be repatriated were also coded. Finally, symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder related to experiences in ISIS were coded dichotomously.

Results

At present, 261 interviews (211 men and 50 women) have been coded and analyzed. In understanding vulnerabilities, motivations, and influences for joining, it is useful to distinguish between those who were living in areas that ISIS took over before they joined (“locals”) and those who either traveled to join ISIS, attempted to travel to join ISIS, or encouraged others to travel to join ISIS from abroad (“foreigners”). Differences between men and women in all of the thematic categories highlight the importance of considering gender in addressing militant jihadist radicalization and recruitment (Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2021).

Vulnerabilities

Among the locals, the most common vulnerabilities for men were poverty (38.2 percent), unemployment or under-employment (24.7 percent), and having a parent who died during the interviewee’s childhood (14.6 percent). The most common vulnerabilities for local women were poverty (44.4 percent), having a parent who died during the interviewee’s childhood (22.2 percent), and prior traumatic events (22.2 percent).

Among the foreigners, the most common vulnerabilities for men were struggling with substance abuse (23.8 percent), having a history of criminality (19.7 percent), and prior traumatic events (18.9 percent). The most common vulnerabilities among local women were growing up in a dysfunctional household (31.7 percent), prior traumatic events (24.4 percent), and parental separation or divorce (22.0 percent).

Influences

With regard to influences, the most common among the local men were ISIS recruiters they met in person (32.6 percent), preachers (20.2 percent), and friends (19.1 percent). The most common influences for local women were spouses (33.3 percent), parents (33.3 percent), and extended family members (22.2 percent). Thus, internet-based recruitment was less important for locals, with 13.5 percent of local men and no local women having any internet-based recruitment or facilitation in their decisions to join ISIS, and only one local man being recruited solely over the internet.

In contrast, the most common influences among the foreign men were content they viewed on YouTube (50.8 percent), friends (45.9 percent), and content they saw in the mainstream media (37.7 percent). The most common influences for foreign women were spouses (56.1 percent), ISIS recruiters they met online (19.5 percent), content they viewed on YouTube (17.1 percent), and friends (17.1 percent). Internet recruitment was therefore much more common among the foreigners, with 79.5 percent of foreign men and 56.1 percent of foreign women having any internet-based recruitment or facilitation in their decisions to join ISIS, and 31.1 percent of foreign men and 22.0 percent of foreign women being recruited solely over the internet.

Motivations

Motivations were related to more tangible needs for the locals, with the most common motivations for local men being employment (40.4 percent), fulfillment of basic needs (29.2 percent), and the desire to fight for Sunni rights (18.0 percent). Similarly, the most common motivations for local women were fulfillment of basic needs (55.6 percent), safety for oneself and one’s family (55.6 percent), and the desire to keep one’s family together (44.4 percent).

Among the foreigners, however, motivations were related to loftier goals. For the foreign men, the most common motivations were the desire to help the Syrian people (56.6 percent), the desire to solidify one’s Islamic identity (41.0 percent), and the desire to build a Caliphate (32.0 percent). For the foreign women, the most common motivations were the desire to solidify one’s Islamic identity (48.8 percent), the desire to keep one’s family together (41.5 percent), and the desire to help the Syrian people (24.4 percent). The motivation to help the Syrian people among foreign men and women was largely driven by knowledge of the atrocities committed against Syrian civilians by the Assad regime, and by the perceived inaction against such acts by Western powers (Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2022).

Roles and Experiences

After joining ISIS, the interviewees held a variety of roles. The local men most commonly acted as fighters (24.7 percent), as border patrol and guards (23.6 percent), and in other administrative roles (16.9 percent). The local women all acted as wives and mothers, and two local women were also members of ISIS’s morality police. The foreign men most commonly acted as border patrol and guards (43.4 percent), as fighters (43.4 percent), and in other administrative roles (26.3 percent). The foreign women all acted as wives and mothers, and one woman also acted as a nurse.

The interviewees also had a wide array of experiences. As victims, the most common experiences for local men were bombings (21.3 percent), imprisonment by ISIS (18.0 percent), and physical torture (7.9 percent). The most common sources of victimization for local women were bombings (66.7 percent), forced marriages (55.6 percent), and being widowed due to ISIS-related violence (55.6 percent). The most common sources of victimization for foreign men were bombings (73.8 percent), being imprisoned by ISIS (42.6 percent), and being wounded in bombings (19.7 percent). For foreign women, the most common sources of victimization were bombings (65.9 percent), being widowed due to ISIS-related violence (43.9 percent), and being imprisoned by ISIS (22.0 percent).

The most common atrocities witnessed by the local men were seeing executions (27.0 percent), seeing torture (23.6 percent), and hearing about the deaths of family members (18.0 percent). For local women, the most common atrocities witnessed were hearing about the deaths of family members (88.9 percent) and seeing torture (22.2 percent). Among the foreign men, the most common atrocities witnessed were hearing about the deaths of family members (17.2 percent), seeing executions (16.4 percent), and seeing executed corpses (16.4 percent). Among the foreign women, the most common atrocities witnessed were hearing about the deaths of family members (34.1 percent), seeing executed corpses (9.8 percent), and seeing executions (4.9 percent).

Finally, although the participants were warned not to incriminate themselves, some did admit to participating in some of ISIS’s actions. Among the local men, these actions included killing others on the battlefield (6.7 percent), performing beheadings (4.5 percent), performing non-beheading executions (1.1 percent), performing physical torture (1.1 percent), and owning a slave (1.1 percent). One local woman admitted to biting, flogging, and beating other women as part of her role in the hisbah, ISIS’s morality police. Among the foreign men, the actions performed as part of ISIS included killing others on the battlefield (4.1 percent), performing non-beheading executions (1.6 percent), performing physical torture (1.6 percent), and performing beheadings (0.8 percent).

Disillusionment and Deradicalization

By the time of their interview, many of the interviewees had become disillusioned at least by some aspects of ISIS, if not with the group as a whole. For the local men, the most common sources of disillusionment were ISIS’s mistreatment of civilians (32.6 percent), ISIS’s mistreatment of women (19.1 percent), and ISIS’s mistreatment of its own members (16.9 percent). For the local women, the most common sources of disillusionment were ISIS’s mistreatment of women (66.7 percent) and the lack of food (55.6 percent). The most common sources of disillusionment for the foreign men were the lack of food (31.1 percent), ISIS’s mistreatment of foreign fighters (29.5 percent), and bad governance by ISIS (26.2 percent). Among the foreign women, the most common sources of disillusionment were ISIS’s mistreatment of women (65.9 percent), the lack of food (24.4 percent), ISIS’s attacks outside of its own territory (19.5 percent), and ISIS’s mistreatment of its own members (19.5 percent).

Some of the participants could be considered to have “spontaneously deradicalized,” meaning that they became almost or completely deradicalized without going through a former deradicalization program, but rather by what they experienced in ISIS (Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020b). These individuals were not people who joined ISIS against their will or to meet their basic needs but never actually believed in the militant jihadist ideology; rather, they became completely disillusioned with the ideology as a result of their experiences. According to these criteria, 25.8 percent of the local men and none of the local women could be considered to have spontaneously deradicalized, and 27.9 percent of the foreign men and 46.3 percent of the foreign women could be considered to have spontaneously deradicalized.

Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project

In an effort to disrupt and combat ISIS’s prolific recruitment on mainstream and encrypted apps, the International Study for the Study of Violent Extremism [ICSVE], at the request of the U.S. State Department, began creating counter narrative video clips featuring real ISIS insiders to denounce the group. The counter narrative videos are cut from the interviews described above.

Method

The interviews, which are video recorded with the interviewees’ consent, are in-depth psychological interviews that are also used for psychological research as described above. The interviews were conducted primarily in prisons in Iraq and Northeast Syria (run by the Syrian Democratic Forces [SDF]), as well as in prisons, community, and home settings in Belgium, Albania, Kosovo, Turkey, and Kyrgyzstan. Each interview lasts approximately one and a half hours, though some have lasted up to five hours, and follow a chronological structure as described above.

The videoed interviews are then transcribed and re-translated to supplement and correct any errors that may have been made by the translators during the interviews. The videos are then scripted and edited down to create a one- to five-minute long video script, primarily narrated by the interviewee, who denounces the group and its ideology as un-Islamic, corrupt, and overly brutal. Actual ISIS footage from the group’s own propaganda is used to illustrate the parts of the video when the narrator is not on camera. The theory behind creating these videos is to use an actual disillusioned ISIS insider denouncing the group as unIslamic, corrupt, and brutal, speaking in simple language while emotionally evocative scenes are shown, in order to engage the same audience as ISIS. For this reason, a photo from ISIS propaganda is also used as the thumbnail and the video is titled with an ambiguous or pro-ISIS name in order to attract ISIS’s target audience who mistake it for an ISIS video but instead receive a very strongly emotionally charged anti-ISIS message. The videos are subtitled in the 27 languages in which ISIS recruits and uploaded to YouTube, Facebook, and ICSVE’s website. They are also used in campaigns and research projects on Facebook, Telegram, and Instagram, and sent out to practitioners working face-to-face with people vulnerable to ISIS recruitment. The videos are free for anyone to use in fighting ISIS (without profiting from them), as are the study guides written specifically for use by teachers, prison workers, police, and preventing and countering violent extremism [P/CVE] professionals. The study guides include a short main message, a narrative description of the video, a transcript of the video, discussion questions, and Islamic scriptures used to refute ISIS’s claims and ideology.

Results

Global Reach

Since ICSVE’s founding in 2015, we have run 173 counter narrative ad campaigns on Facebook in partnership with META. The ad campaigns, paid for with Facebook ad credits, use the Breaking the ISIS Brand counter narrative videos, the creation of which has been generously funded by the Embassy of Qatar in Washington, D.C. The videos feature ISIS insiders – male and female defectors, returnees, and imprisoned cadres – denouncing the group as unIslamic, corrupt, and overly brutal. The speakers honestly describe their stories, explaining what attracted them to ISIS in the first place, and then warn others not to follow the same path through their depictions of what they actually experienced in ISIS. These experiences include being imprisoned, being tortured, and watching friends and family members die. The speakers are authentic and genuine, pushing viewers to empathize and to feel the same emotional connection to the counter narrative video than they might feel when watching militant jihadist online propaganda. Although it is not feasible to measure behavioral change that occurs as a result of watching our videos, we can measure the awareness-raising impact that the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project has had in the countries from which ISIS recruited the most fighters and members. One such number that provides insight is the “reach” number, which indicates the number of Facebook users on whose Facebook feeds the ads have appeared. Across all of ICSVE’s Facebook campaigns, we have reached 39,561,370 Facebook users. Our videos have been viewed in their entirety 2,774,043 times, and the ads have directly resulted in 1,775,109 views of TheRealJihad.org, which is an ICSVE-run website which includes blog posts written by an Islamic scholar refuting ISIS’s claims, the complete collection of ICSVE’s counter narrative videos, and links to online and on-the-ground counseling and deradicalization resources. The campaigns have also received 17,632 comments and been shared 23,316 times. This document includes a sample of campaigns which demonstrate the awareness raising impact of the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project.

Fighting ISIS on Facebook and Telegram Using Direct Posting Methods

Despite takedown policies, ISIS and its supporters remain active on Facebook. During ICSVE’s first Facebook campaigns, ICSVE staff were able to search on hashtags and use data scraping to identify 50 English and 77 Albanian speaking Facebook profiles that endorsed, liked, shared, or provided other evidence of support for ISIS. Two Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project videos were then posted, tagging those profiles. Through these initial studies, ICSVE found that it was possible to identify and penetrate ISIS territory on Facebook. Indeed, the counter narrative videos were even shared in pro-ISIS groups by users who mistakenly believed them to be ISIS propaganda. Thus, tagging ISIS endorsers in the counter narrative videos which were named to look like ISIS propaganda and posting the videos in pro-ISIS groups led to an amplification of the counter narrative message, as the videos were shared to large numbers of vulnerable audiences. The sharing and liking of the videos continued until the users began to watch the videos in their entirety, at which point they realized that the videos were not produced by ISIS and subsequently cursed at and blocked the accounts that had originally posted the videos. Still, even after the pro-ISIS Facebook users realized the true purpose of the counter narratives, they were moved to engage emotionally with ICSVE by commenting on the counter narratives. Such behavior indicates that the users found the counter narratives evocative and the speakers credible; had they not, they would not have felt the need to refute their message.

While Facebook and other mainstream social media platforms have instituted takedown policies for terrorist material and cooperated with government entities to identify users promoting such material, encrypted apps like Telegram have staunchly refused to provide such information, holding that doing so would infringe upon their users’ rights to free speech and to communicate free of government surveillance. This has made Telegram and other similar apps attractive to ISIS. ICSVE sought to penetrate Telegram on its own, therefore, in order to determine if it were possible for counter terrorism organizations and agencies to identify pro-ISIS users without assistance from the company. ICSVE was able to identify, join, and post counter narrative videos in active ISIS chat groups, and discussions among users ensued in reaction to the counter narrative videos, though the discussions and users were difficult to track. However, ICSVE researchers were able to learn the true identities of a few of the pro-ISIS users.

Fighting ISIS Through Facebook Ads

Thus far, the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project videos have reached and engaged the largest audiences through Facebook ad campaigns. Supported by Facebook ad credits, ICSVE has run over 150 Facebook campaigns in multiple languages all over the world, reaching over 39 million Facebook users. In the forthcoming sections, we discuss highlights from some recent counter narrative campaigns.

Campaigns in the European Union. As part of a grant from the European Commission’s Civil Society Empowerment Programme’s Internal Security Fund – Police, ICSVE ran a series of eight campaigns in which we utilized one-minute versions of our counter narrative videos, which we found to hold viewers’ online attention better than the longer videos. For the first two campaigns, we used different videos in different countries, tailoring the ads to find the speakers whom we thought would be most relatable to the specific target audience. However, we found that certain videos tended to perform better regardless of country, and therefore switched our strategy for the following campaigns. For Campaign 3, we ran two videos in each of the countries (viewers saw one or the other), and for Campaigns 4 through 8, all viewers were shown the same video. Each campaign was run for 13 to 14 days on Facebook, with the exception of EU2, which was run on Instagram.

In total, the first EU Facebook counter narrative campaign reached 1,068,287 Facebook users and videos were viewed for at least 15 seconds 893,526 times. The videos were viewed in their entirety 277,507 times, indicating a 31.1 percent rate of retention for viewers who watched the video for 15 seconds and then completed the video. The counter narrative with the most complete views was the video run in Italy with Italian subtitles (196,489 complete views), and the counter narrative with the highest rate of viewer retention was the video run in Belgium with Arabic subtitles (43.0 percent retention from 15 second to the end of the video) (Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020c).

In total, the EU Instagram counter narrative campaign reached 809,218 Instagram users and videos were viewed for at least 15 seconds 167,590 times. The videos were viewed in their entirety 21,542 times, indicating a 12.9 percent rate of retention for viewers who watched the video for 15 seconds and then completed the video. The counter narrative with the highest number of complete views was the video run in Italy with Italian subtitles (13,168 complete views), and the counter narrative with the highest viewer retention was the video run in France with Arabic subtitles (38.0 percent of viewers who watched for 15 seconds completed the video) (Speckhard & Ellenberg, 2020d).

The third campaign utilized two different videos, one featuring a Belgian woman, Laura Passoni, and the other featuring a German woman, Jamila. Across countries and languages, the videos received 1,920,162 15-second views, 1,267,487 45-second views, and 1,146,777 complete views. On average, 59.7 percent of all 15-second views became complete views. Additionally, it appears that the longer a viewer watched the video, the more likely they were to finish the video, as 71.2 percent of all 45-second views became complete views. On average across countries and languages, viewers watched these videos for 25.09 seconds, shared the videos 9.76 times, saved them 7.32 times, commented on them 5.87 times, and reacted (e.g., “like,” “haha,” “sad,” “angry”) 29.83 times.

The fourth campaign utilized a Somali-European speaker who spoke about being radicalized to militant jihadism through listening to sermons by Anwar al-Awlaki. Across countries and languages, the video received 365,693 15-second views, 156,047 45-second views, and 107,918 complete views. On average, 29.5 percent of all 15-second views became complete views. Additionally, it appears that the longer a viewer watched the video, the more likely they were to finish the video, as 69.2 percent of all 45-second views became complete views. On average across countries and languages, viewers watched these videos for 16.32 seconds, shared the videos 13 times, saved them 5.13 times, commented on them 17.73 times, and reacted (e.g., “like,” “haha,” “sad,” “angry”) 52.32 times.

The fifth campaign utilized a Dutch male speaker of Moroccan descent. Across countries and languages, the video received 461,656 15-second views, 195,710 45-second views, and 121,880 complete views. On average, 26.4 percent of all 15-second views became complete views. Additionally, it appears that the longer a viewer watched the video, the more likely they were to finish the video, as 62.3 percent of all 45-second views became complete views. On average across countries and languages, viewers watched these videos for 16.42 seconds, shared the videos 25.13 times, saved them 7.80 times, commented on them 17.63 times, and reacted (e.g., “like,” “haha,” “sad,” “angry”) 79.39 times.

The sixth campaign, featuring a Belgian speaker of Moroccan descent, was run only in Arabic (in Belgium, France, Greece, Italy, Netherlands, and Sweden), Albanian (in Austria, Belgium, France, Greece, and Italy), French (in France and Belgium), and Dutch (in the Netherlands and Belgium). These first campaigns were run before separately because of a translation delay for the remaining languages. Across countries and languages, the video received 256,681 15-second views, 103,300 45-second views, and 24,681 complete views. On average, 9.6 percent of all 15-second views became complete views. Additionally, it appears that the longer a viewer watched the video, the more likely they were to finish the video, as 23.9 percent of all 45-second views became complete views. On average across countries and languages, viewers watched these videos for 16.53 seconds, shared the videos 20.15 times, saved them 9.00 times, commented on them 21.73 times, and reacted (e.g., “like,” “haha,” “sad,” “angry”) 85.33 times.

The seventh campaign featured a Belgian speaker of European descent. Across countries and languages, the video received 236,299 15-second views, 99,610 45-second views, and 54,012 complete views. On average, 22.9 percent of all 15-second views became complete views. Additionally, it appears that the longer a viewer watched the video, the more likely they were to finish the video, as 54.2 percent of all 45-second views became complete views. On average across countries and languages, viewers watched these videos for 12.77 seconds, shared the videos 2.33 times, saved them 6.68 times, commented on them 4.77 times, and reacted (e.g., “like,” “haha,” “sad,” “angry”) 25.79 times.

The eighth campaign featured a British speaker of European descent. Across countries and languages, the video received 81,710 15-second views, 29,897 45-second views, and 16,217 complete views. On average, 25.59 percent of all 15-second views because complete views. Additionally, it appears that the longer a viewer watched the video, the more likely they were to finish the video, as 54.24 percent of all 45-second views became complete views. On average across countries and languages, viewers watched these videos for 9.59 seconds, shared them 2.60 times, saved them 6.44 times, commented on them 2.50 times, and reacted to them 17.26 times.

All of the campaigns directed viewers to TheRealJihad.org, an ICSVE-run website which features blog posts by an Islamic scholar refuting militant jihadist claims, a complete collection of full-length counter narrative videos, and links to online and on-the-ground resources for counseling and deradicalization. Resources based in the European Union which are highlighted on the website are located in Belgium, Denmark, Germany, Italy, the Netherlands, Spain, Sweden, and France. Since Campaign 1 began on April 17, 2020, TheRealJihad.org has received 5,243 new visitors from Italy, 4,985 new visitors from France, 3,141 new visitors from Germany, 2,552 new visitors from Belgium, 2,403 new visitors from Greece, 1,893 new visitors from the Netherlands, 1,578 new visitors from Sweden, 877 new visitors from Finland, and 573 new visitors from Austria.

Across all ads, the campaigns received 4,215,727 15-second views, 2,385,421 45-second views, and 1,748,992 complete views. They also received 7,217 reactions and 1,140 comments and were shared 1,530 times and saved 878 times. On average, the viewers watched the videos for 17.17 seconds, and 28.6 percent of viewers who watched the videos for 15 seconds went on to finish the videos.

Probing further about the features of the videos, independent samples t-tests revealed that videos featuring women received a significantly higher average play time (t = -3.610, p = .000) and retention rate (t = -2.155, p = .002), than videos featuring men. However, videos featuring men received significantly more reactions (t = 2.744, p = .001), comments (t = 2.369, p = .004), and shares (t = 2.287, p = .024), than videos featuring women. We also found significant differences based on whether the speaker was of European or non-European descent. Speakers of European descent (who were converts to Islam) received a significantly higher average play time (t = 1.103, p = .000). In contrast, speakers of immigrant descent (who were born Muslim) received significantly more reactions (t = -3.274, p = .000), comments (t = -2.803, p = .001), and shares (t = -2.558, p = .004).

Given these differences, it seems that the metrics can be separated into two categories, viewership (15-second views, 45-second views, complete views, average play time, and retention rate), and engagement (reactions, comments, shares, and saves). With a few exceptions, it appears that the intercorrelations within categories are stronger than those between categories. Therefore, it is clear that metrics related to viewership are more strongly correlated with one another than they are to those related to engagement, and vice versa.

Campaigns in Trinidad and Tobago. As part of a grant from the U.S. Embassy in Trinidad and Tobago, we ran a series of three counter narrative campaigns. The first Facebook counter narrative campaign ran from July 16, 2021, to July 29, 2021. The ad reached 102,944 Trinidadians located in Rio Claro, Chaguanas, Diego Martin, and San Juan-Laventille, the locations from which the majority of Trinidadian ISIS foreign fighters left. This means that the ad has appeared on the Facebook feed of over 35 percent of all of the people living in these areas. This number also comprises over 10 percent of all Facebook users located in Trinidad and Tobago. The entire video was viewed 11,578 times. Of the viewers who watched 25 percent of the video, 19.7 percent went on to finish the video, and of the viewers who watched 50 percent of the video, 38.1 percent went on to finish the video, demonstrating moderately strong viewer retention and indicating that viewers in these areas are engaged with the counter narrative video. This relatively high level of viewer retention is especially promising, given that the ad campaign was optimized for landing page views, not video views. Demographically, the plurality of complete video views (18.2 percent) came from male Facebook users aged 35 to 44, which is consistent with the demographic of foreign fighters from Trinidad. In total, however, men were not more likely to watch the complete video than women were. The age distribution of complete video viewers was normal, with 88.6 percent of viewers ranging in age from 25 to 54, 7.6 percent ranging in age from 18 to 24, and 3.9 percent ranging in age from 55 to 64.

As a direct result of the ad campaign, TheRealJihad.org, our landing webpage with all of the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative videos and many articles countering how militant and terrorist groups misinterpret Islam, was viewed 2,639 times. However, during the two weeks that the add was running, 3,021 different visitors to TheRealJihad.org were located in Trinidad and Tobago, suggesting that Facebook ad viewers may be returning to the website independently or referring others to the website. This inference is supported by the fact that all visitors to the website during that period were new visitors. Additionally, 10.97 percent of all visits to TheRealJihad.org involved the user moving between pages on the website, rather than visiting only the home page. Since inception of this grant, we have also added 18 new blog posts to the website detailing various aspects of Islam and refuting terrorist claims.

From August 13, 20201, to August 27, 2021, we ran an Instagram ad campaign using a carousel of six images, each with a short quotation from the original counter narrative video which was used in the associated Facebook campaign. The ad reached 82,227 Trinidadians located in Rio Claro, Chaguanas, Diego Martin, and San Juan-Laventville, the locations from which the majority of Trinidadian foreign fighters left. This means that the ad has appeared on the Instagram feed of approximately one third of all of the people living in these areas. This number also comprises approximately 16 percent of all Instagram users in Trinidad and Tobago. As a direct result of the Instagram campaign, TheRealJihad.org landing page was viewed 1,363 times. However, during the two-week period during which the ad was running, 4,486 users located in Trinidad and Tobago viewed TheRealJihad.org, and 13.94 percent of Trinidadian visitors to the website viewed more than just one page on the website. These metrics suggest that viewers of the Instagram ad, as well as the Facebook ad run during the previous month may have referred their friends and family members to the website.

One reason for launching a counter narrative campaign on Instagram was to reach younger viewers, who may be more vulnerable to terrorist radicalization and recruitment than older people. Although we were not able to disaggregate landing page views by age and gender, we were able to perform this analysis for “link clicks,” a metric which includes landing page views in addition to other times that people clicked on a link associated with the ad, such as the profile page for therealjihad_official Instagram account. The plurality of link clicks (23 percent) came from men aged 35-44, but the vast majority of link clicks (60.8 percent) still came from males and females aged 35 and older, despite using a platform that is generally considered more popular among young people.

The third campaign ran for longer and was aimed at increasing viewership rather than directing traffic to TheRealJihad.org. Thus, between October 1, 2021, and December 6, 2021, we gleaned 48,568 25 percent views of the five-minute counter narrative video. The video received 11,893 complete views, thus resulting in a viewer retention rate of 24.5 percent, with an average play time of eight seconds. This retention rate was higher than the retention rate for the first campaign, described above, although it received nearly the same number of complete views. The ad reached 195,241 Trinidadian viewers in located in Rio Claro, Chaguanas, Diego Martin, and San Juan-Laventille, the locations from which the majority of Trinidadian ISIS foreign fighters left. This reach number was also greater than that of the first campaign, although this campaign ran on Facebook for far longer. Finally, although the primary goal of this campaign was to generate views, TheRealJihad.org was nevertheless visited 25 times by users from Trinidad and Tobago during the period that the campaign was running.

Hypertargeted campaigns. ICSVE has also explored a variety of formatting and targeting variations in order to enhance the utility and impact of the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project. In one study, ICSVE utilized an algorithm to identify Facebook profiles deemed most vulnerable to ISIS recruitment and exposure to ISIS propaganda. ICSVE then hyper-targeted 16 Facebook campaigns, consisting of 10 different counter narrative videos, at vulnerable Facebook users. While viewer retention remained fairly low, the hyper-targeted viewers were more likely than general audiences to watch the complete video, and comments confirmed that the counter narratives were reaching a population previously exposed to ISIS-related content and that they were producing emotional responses (Speckhard et al., 2020).

Comment analysis. Comment analysis has been a critical aspect of ICSVE’s studies of counter narrative success. In all campaigns, the comments are used as a measure of whether the campaigns are reaching the correct audiences and if they are evoking strong emotions, as ISIS videos do. While some commenters do indicate slight attitudinal changes as a result of watching the video, such as a Jordanian commenter who wrote, “This is the first time for me to hear about Daesh [ISIS] that way,” there is no way to accurately measure behavioral change as a direct result of the counter narratives.

Comments were explored more in-depth in a set of Facebook campaigns run in Iraq, Jordan, Saudi Arabia, Tunisia, and the Balkans (Kosovo, Albania, Bosnia and Herzegovina, and Montenegro). Very few of the comments on Facebook are overtly pro-ISIS, possibly due to privacy concerns on Facebook. However, some commenters accuse the speaker of lying or ICSVE of working for a government entity. In focus groups, the speakers are almost always seen as credible, so attacking the speaker as a liar online is more likely an expression of anger at the denunciation of ISIS or as an insult to their national pride when the speaker is of the same nationality as the commenter. Other comments are straightforward in their negative regard for ISIS, either by expressing hate and anger toward the speaker or compassion for the speaker and anger at ISIS for their manipulation. All of these comments, positive and negative, demonstrate the ability of the counter narratives to elicit strong emotions that move viewers to take the time to comment on the videos and even engage in debate with other commenters. Many comments, however, portray a negative but nevertheless non-constructive view of ISIS. This study found a worrying trend of comments that were anti-ISIS but promoted conspiracy theories that the United States, Israel, Saudi Arabia, and the West in general created ISIS in order to destroy Islam. Fewer comments also invoke Turkey and Iran as sponsors of ISIS and other terrorist groups. For instance, one commenter in Jordan wrote, “This is made by the westerners to destroy Arab countries for the sake of those monkeys and pig Zionists.” An Iraqi commenter wrote, “Who says you didn’t kill or destroyed houses, you all are not honorable neither European, American, Israeli, Iranian you all Daesh [ISIS].” Another Iraqi commenter on a previous Facebook campaign wrote, “What Muslims, these are Jews that pretend to be Muslim to distort Islam, conspire and separate between Muslims for the sake of tearing Mohammed’s nation.” A commenter in Kosovo wrote, “ISAL [sic] is American killing army supported by money from NATO protection racket. Mafia!” Such comments indicate a further challenge in delegitimizing the overarching militant jihadist ideology rather than ISIS as a specific group, as believers in those conspiracies who do not support ISIS may still be drawn to groups like al Qaeda which focus more on fighting the “far enemy” while proselytizing to other Muslims, rather than declaring Shia and even other Sunni Muslims to be apostates and the primary enemy (Speckhard et al., 2019).

For the first Facebook campaign run in Trinidad and Tobago, the counter narrative video received 515 reactions (all “like” or “love”) and was shared 193 times. It also received 30 comments.

Many comments were quite insightful, related to the topic of the counter narrative video, which was ISIS’s enslavement of Yazidi women. One such conversation is transcribed exactly below:

Original poster: The question for Islam is whether African slavery is part of ANY modern solution in their Holy Book.. The answer to that question will determine the future of that religion on Our Continent and in Our diaspora.. Reparations is the conversation ..!!!

Respondent 1: [OP] well first of all the African slavery or ‘Trans Atlantic Slave Trade’ is not in the Quran but actually in the Bible..so the question should be was lawful according to the words of God or the scriptures the God gave man

OP: [R1] Not lawful for a “Christian” people.. Reparation is the conversation..!!!

Respondent 2: [OP] Islam started the abolishment of slavery long before the Western world. Many converts were ex-slaves and the slaves brought in the Christian Caribbean were once free Muslims. The Qur’an and the traditional practices of Prophet Muhammad (pbuh) abolished slavery and girl child infanticide.

R1: [R2] that don’t matter because they started that same same [sic] slave trade that they abolished and caused the second slave trade to begin because those that sold Africans into slavery learnt that trade from their former slave masters and when they went back with that new knowledge they used it for their own personal gain.

Respondent 3: [R1] so true

OP: [R2] So sad but it is a conversation that We the African diaspora MUST have… NO religion nation organization nor group must target Africans for enslavement on planet Earth nor any other place humans may inhabit EVER again..!!! Equal rights and justice to all mankind.. Reparations is the conversation..!!!

While other commenters debated religion in general, only one comment was blatantly Islamophobic (“The devil religion”), which is low in comparison to comments on other counter narrative videos run in Muslim-minority countries. However, this video was run in areas of Trinidad where Islam is more prevalent. One commenter criticized the speaker, saying, “So they had to commit the atrocity to discover it was wrong? What’s up with that?” Other commenters appeared more sympathetic, however, commenting, “Allah tala knows everyone’s heart inshallah Allahu akbar,” which means, “God almighty knows everyone’s heart God willing, God is great.” Another wrote, “Assalamualaikum bro keep safe.” This sympathy might be due to recognition of the speaker, perhaps simply as another Trinidadian Muslim, or due to literal recognition, as one commenter wrote, “Zyed [the speaker’s name] bai wey longtime i ain’t see you.”

With regard to the Instagram carousel campaign in Trinidad and Tobago, engagement was high. The ad received 693 likes and 44 comments (not including replies to comments) and was shared 136 times and saved 127 times. The comments were used to assess whether this style of ad was similarly emotionally evocative and engaging, as the counter narrative videos are. Just as we found in the Facebook campaign, some users personally knew the subject of the ad, with one man commenting, “stay strong my brother,” and later responding to another commenter that he “went to school with him.” Another wrote, “Is he ok? I went to school with him. So very sad this entire situation.” A woman responded, “I remember him hope he is ok.” Another commenter wrote, “My old school mate I known you as a humble fella hmm only God can judge you cause I can’t.” Others were clearly emotionally engaged. One man commented, “And what good u got from venturing over there… Nothing! but pain and sorrows,” and another responded, “an opportunity to see truth and learn from it.” Another commenter responded, “exactly most of the Muslims that went never went for war they went seeking an Islamic environment and ended up in a completely different scenario. On too of that they never had any intention on returning to Trinidad and Tobago [sic].” One commenter wrote simply, “This is sad.” Another wrote, “A second chance is before all of them and the chance for redemption is in their grasp.” Still another commenter wrote, “I would love to hear your his story. Possibly learn from his experience rather than judge or ridicule him. Cause this ain’t nothing to laugh about.”

Still, others were less sympathetic, writing comments such as, “once you in a country like that [ISIS] stay there don’t accept them back here [Trinidad],” though one commenter responded to those comments regarding Trinidad “disowning” those who went to ISIS, “bunch of dunce in these comments but it makes me happy to see the hate for Muslims in Trinidad exposed.” Another commenter simply wrote, “abomination to mankind,” but many made sure to distinguish ISIS from Islam. One wrote, “What they did/do had nothing to do with Islam. Just like a Mexican gangster full believes and practices the catholic faith yet kill ppl so did they. Religion is not to blame but the individual themselves.”

One commenter appeared to be supportive of ISIS, which we did not see in the Facebook campaign: “They say what they want about that brother a real SOLDIER OF ALLAH(SWT) probably ALLAH not ready for him as yet and the lies will continue on him may ALLAH (SWT) PROTECT HIM.” This comment was followed by a series of emojis, including a black flag and an index finger, both commonly used by ISIS supporters online. Another commenter did not seem to understand that the subject of the ad was imprisoned and cited a conspiracy theory: “If he is a freeman that proves the CIA running the whole operation.” Another commenter later echoed this sentiment, writing, “they were working for the us fooled into thinking it was a revolution he’s just lucky to be alive all the rest of guys died.”

Fighting ISIS in Face-to-Face Settings

As mentioned previously, the Breaking the ISIS Brand counter narrative videos are free for practitioners around the world to use in their work preventing individuals, particularly at-risk youth, from joining ISIS or committing attacks on its behalf. In order to support these practitioners, we have created training manuals which include guides to using the videos as part of more holistic interventions, as well as study guides tailored for each individual video, including discussion questions and Islamic scriptures related to the topics covered in each video (Speckhard, 2021; Speckhard, Ellenberg, & Ali, 2021). Anecdotally, we have learned from practitioners around the world that the videos and training materials are useful in their work, including one British counselor who convinced a teenager not to travel to join ISIS using one of the Breaking the ISIS Brand videos of a teenaged would-be suicide bomber. The same video was shown to an imprisoned ISIS emir who, upon watching it, lowered his head and admitted that ISIS was wrong to use children as suicide attackers (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2017a). Additionally, police and other preventing and countering violent extremism professionals around the world report frequently using the videos in training and education sessions.

Focus group testing. These instances of success using the videos are promising and are bolstered by results from multiple focus groups in different populations. A sample of 75 American university students reporting finding the videos authentic and disturbing, engendering feelings of anger and fear, feelings and messaging they believed made the videos useful to convince others not to join ISIS. Despite the limitation of using a normative American sample which, as expected, already held negative views of ISIS, one third of the sample reported that the videos changed their minds about ISIS “by providing evidence that ISIS was even worse than they had suspected” (McDowell-Smith, Speckhard, & Yayla, 2017, p. 69). Additionally, in four focus groups with Somali American young adults living in San Diego, California, we found that viewers in this demographic group, a group which is particularly likely to be targeted by militant jihadist propagandists from both ISIS and al Shabaab, found the videos authentic and emotionally evocative. Like the first sample of university students described above, these focus group members began with relatively negative views of ISIS but nevertheless reported that the videos made them think more negatively about ISIS and believed that the videos could convince someone not to join ISIS or al Shabaab (Speckhard, Shajkovci, & Ahmed, 2018; Speckhard, Ellenberg, & Ahmed, 2020). Similar results have also been found in focus groups conducted with young people in Jordan (Braizat et al., 2017), as well. In Kosovo and Kyrgyzstan, youth as well as police, teachers, and security professionals also participated in focus groups and were enthusiastic about using the videos in their work (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2017b; Speckhard & Esengul, 2017).

Prevention and Remediation

With ISIS continuing to mount attacks and to encourage its followers to prepare for its resurgence, it is incumbent upon P/CVE, intelligence, security, and law enforcement professionals to be proactive in the fight against ISIS and other militant jihadists’ radicalization and recruitment efforts. Those working to take individuals off of the terrorist trajectory benefit from the knowledge of the existential needs and motivations that can make someone vulnerable to recruitment by groups which offer them a purpose, a sense of dignity, a feeling of belonging, and a sense of personal significance (Speckhard, 2016; Kruglanski et al., 2014). Thus, logical arguments alone are not enough to turn such an individual away from a group which promises to fill these needs. Rather, emotional appeals are required, in addition to the provision of services and opportunities which can provide an alternate route to feelings of self-worth. Additionally, understanding the power of online recruitment, specifically in the case of those living outside of conflict zones, is critical. Indeed, although it may be rare, it is possible for an individual to be radicalized and recruited to travel to join a terrorist group through online interactions alone. Social media allows people continents apart to feel connected to, and indeed responsible for, one another. This feeling of interconnectedness was demonstrated to motivate tens of thousands of men and women to travel to defend Syrian civilians, wage jihad, and build a Caliphate they believed would be a pure, Islamic utopia. Currently, that same feeling is motivating people to send money to break men and women out of prison in Northeast Syria or to take up arms and attack innocent civilians in ISIS’s name. In the face of such a challenge, however, practitioners are better equipped than ever before with the knowledge and the resources to prevent, counter, and intervene in militant jihadist radicalization and recruitment.

First, online recruitment and radicalization can be prevented through the use of credible, emotionally evocative personal narratives which refute the arguments made by militant jihadists and expose the dark reality behind their promises of utopia and glory. Of course, face to face preventative actions are also critical, especially those which address the unique circumstances under which a particular individual is being radicalized and recruited. Second, those on the front line of identifying those at risk for radicalization, including teachers, social workers, religious and community leaders, and police officers, can be vigilant for the signs of radicalization and can take steps to redirect these individuals, offering them prosocial and productive opportunities for belonging, meaning, and significance. These opportunities could, for instance, include non-extreme religious activities such as youth group participation (Cox, Nozell, & Buba, 2017), participation in sports teams (Grossman, Johns, & McDonald, 2014), and participation in non-violent social activism (Briggs, 2010). Similarly, societal actors can also work to ameliorate the grievances exploited by terrorist recruiters, such as by passing strong anti-discrimination laws and encouraging freedom of religious expression and by working to reduce police brutality toward and targeting of marginalized groups.

After an individual has already become involved in terrorist activity, many of these recommendations may seem to be moot. Nevertheless, there are steps that practitioners and policy makers can take to rehabilitate and reintegrate these people into society, alongside holding them accountable for their actions. As mentioned above, it is possible that the experience of being in a terrorist group can lead an individual to become disillusioned and even deradicalized, without any formal rehabilitation program. For many people, however, it is likely that a more structured program will be necessary. These programs should include religious counseling (e.g., “Islamic Challenge”) by scholars who are perceived as credible by the individual and can carefully and effectively take apart each argument made my militant jihadists. They should also include a psychosocial aspect which addresses the underlying psychological and social needs which led the individual to become involved in terrorism as well as the trauma that the individual may have experienced during their time in the terrorist group. In a similar vein, the Islamic Challenge portion of a rehabilitation program can cause great cognitive dissonance or even have a traumatic effect when the individual realizes that the violent actions that they undertook as part of a terrorist group were not morally justified or divinely sanctified. These feelings must be addressed by a mental health professional so that the individual does not attempt to resolve their cognitive dissonance by slipping back into the militant jihadist ideology (Speckhard, 2011).

Reference for this article: Speckhard, Anne, and Ellenberg, Molly (2022). Talking Back to ISIS: Understanding, Preventing, and Remediating Militant Jihadist Propaganda and Recruitment. ICSVE Research Reports.

About the Authors:

Anne Speckhard, Ph.D. is Director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE) and serves as an Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Georgetown University School of Medicine. She has interviewed over 700 terrorists, violent extremists, their family members and supporters in various parts of the world including in Western Europe, the Balkans, Central Asia, the Former Soviet Union and the Middle East. In the past five years, she has in-depth psychologically interviewed over 270 ISIS defectors, returnees and prisoners as well as 16 al Shabaab cadres (and also interviewed their family members as well as ideologues) studying their trajectories into and out of terrorism, their experiences inside ISIS (and al Shabaab). She, with ICSVE, has also developed the Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project materials from these interviews which includes over 250 short counter narrative videos of terrorists denouncing their groups as un-Islamic, corrupt and brutal which have been used in over 150 Facebook and Instagram campaigns globally. Since 2020 she has also launched the ICSVE Escape Hate Counter Narrative Project interviewing over 50 white supremacists and members of hate groups developing counternarratives from their interviews as well. She has also been training key stakeholders in law enforcement, intelligence, educators, and other countering violent extremism professionals, both locally and internationally, on the psychology of terrorism, the use of counter-narrative messaging materials produced by ICSVE as well as studying the use of children as violent actors by groups such as ISIS. Dr. Speckhard has given consultations and police trainings to U.S., German, UK, Dutch, Austrian, Swiss, Belgian, Danish, Iraqi, Jordanian and Thai national police and security officials, among others, as well as trainings to elite hostage negotiation teams. She also consults to foreign governments on issues of terrorist prevention and interventions and repatriation and rehabilitation of ISIS foreign fighters, wives and children. In 2007, she was responsible for designing the psychological and Islamic challenge aspects of the Detainee Rehabilitation Program in Iraq to be applied to 20,000 + detainees and 800 juveniles. She is a sought after counterterrorism expert and has consulted to NATO, OSCE, UN Women, UNCTED, the EU Commission and EU Parliament, European and other foreign governments and to the U.S. Senate & House, Departments of State, Defense, Justice, Homeland Security, Health & Human Services, CIA, and FBI and appeared on CNN, BBC, NPR, Fox News, MSNBC, CTV, CBC and in Time, The New York Times, The Washington Post, London Times and many other publications. She regularly writes a column for Homeland Security Today and speaks and publishes on the topics of the psychology of radicalization and terrorism and is the author of several books, including Talking to Terrorists, Bride of ISIS, Undercover Jihadi and ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Her research has also been published in Global Security: Health, Science and Policy, Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, Journal of African Security, Journal of Strategic Security, the Journal of Human Security, Bidhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies, Journal for Deradicalization, Perspectives on Terrorism and the International Studies Journal to name a few. Her academic publications are found here: https://georgetown.academia.edu/AnneSpeckhard and on the ICSVE website http://www.icsve.org

Follow @AnneSpeckhard

Molly Ellenberg is the Facebook Research Fellow at the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism [ICSVE]. Molly is a doctoral student in social psychology at the University of Maryland. She holds an M.A. in Forensic Psychology from The George Washington University and a B.S. in Psychology with a Specialization in Clinical Psychology from UC San Diego. Her research focuses on radicalization to and deradicalization from militant jihadist and white supremacist violent extremism, the quest for significance, and intolerance of uncertainty. Molly has presented original research at NATO Advanced Research Workshops and Advanced Training Courses, the International Summit on Violence, Abuse, and Trauma, the GCTC International Counter Terrorism Conference, UC San Diego Research Conferences, and for security professionals in the European Union. She is also an inaugural member of the UNAOC’s first youth consultation for preventing violent extremism through sport. Her research has been cited over 100 times and has been published in Psychological Inquiry, Global Security: Health, Science and Policy, AJOB Neuroscience, Frontiers in Psychology, Motivation and Emotion, Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, Journal of Child and Adolescent Trauma, Women & Criminal Justice, the Journal of Strategic Security, the Journal of Human Security, Bidhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies, and the International Studies Journal. Her previous research experiences include positions at Stanford University, UC San Diego, and the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism at the University of Maryland.

References

Barrett, R. (2017). Foreign Fighters and the Threat of Returnees. The Soufan Center, October.

Benmelech, E., & Klor, E. F. (2020). What explains the flow of foreign fighters to ISIS?. Terrorism and Political Violence, 32(7), 1458-1481.

Braizat, F., Speckhard, A., Shajkovci, A., & Sabaileh, A. (2017). Determining Youth Radicalization in Jordan. International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism.

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative research in psychology, 3(2), 77-101.

Briggs, R. (2010). Hearts and minds and votes: The role of democratic participation in countering terrorism. Democratization, 17(2), 272-285.

Cox, A., Nozell, M., & Buba, I. A. (2017). Implementing UNSCR 2250:. United States Institute of Peace.

Grossman, M., Johns, A., & McDonald, K. (2014). “More than a game”: The impact of sport-based youth mentoring schemes on developing resilience toward violent extremism. Social Inclusion, 2(2), 57-70.

Kruglanski, A. W., Gelfand, M. J., Bélanger, J. J., Sheveland, A., Hetiarachchi, M., & Gunaratna, R. (2014). The psychology of radicalization and deradicalization: How significance quest impacts violent extremism. Political Psychology, 35, 69-93.

Malet, D. (2015). Foreign fighter mobilization and persistence in a global context. Terrorism and Political Violence, 27(3), 454-473.

McDowell-Smith, A., Speckhard, A., & Yayla, A. S. (2017). Beating ISIS in the digital space: Focus testing ISIS defector counter-narrative videos with American college students. Journal for Deradicalization, (10), 50-76.

Pokalova, E. (2019). Driving factors behind foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq. Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 42(9), 798-818.

Speckhard, A. (2011). Prison and community-based disengagement and de-radicalization programs for extremist involved in militant jihadi terrorism ideologies and activities. Psychosocial, organizational and cultural aspects of terrorism, 1-14.

Speckhard, A. (2016). The lethal cocktail of terrorism: the four necessary ingredients that go into making a terrorist & fifty individual vulnerabilities/motivations that may also play a role. International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism: Brief Report.

Speckhard, A. (2021). Women in preventing and countering violent extremism: A training manual. United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women.

Speckhard, A., & Ellenberg, M. D. (2020). ISIS in Their Own Words. Journal of Strategic Security, 13(1), 82-127.

Speckhard, A., & Ellenberg, M. (2020). Spontaneous deradicalization and the path to repatriate some ISIS members. Homeland Security Today.

Speckhard, A., & Ellenberg, M. (2020). Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Facebook Campaigns in Europe. Journal of Strategic Security, 13(3), 120-148.

Speckhard, A., & Ellenberg, M. (2020). ISIS and the militant jihad on Instagram. Homeland Security Today.

Speckhard, A., & Ellenberg, M. (2021). ISIS and the Allure of Traditional Gender Roles. Women & Criminal Justice, 1-21.

Speckhard, A., & Ellenberg, M. (2022). The effects of Assad’s atrocities and the call to foreign fighters to come to Syria on the rise and fall of the ISIS Caliphate. Behavioral Sciences of Terrorism and Political Aggression, 14(2), 169-185.

Speckhard, A., Ellenberg, M., & Ahmed, M. (2020). Jihad is our Way: Testing a Counter Narrative Video in Two Somali American Focus Groups. Bildhaan: An International Journal of Somali Studies, 20(1), 8.

Speckhard, A., Ellenberg, M., & Ali, S. (2021). Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project Europe 2021. International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism.

Speckhard, A., Ellenberg, M., & Baddorf, Z. (2021). Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narrative Project: Understanding, Preventing, and Intervening in Militant Jihadi Terrorism and Violent Extremism. In From Territorial Defeat to Global ISIS: Lessons Learned (pp. 94-111). IOS Press.

Speckhard, A., Ellenberg, M., Shaghati, H., & Izadi, N. (2019). Anti-ISIS and Anti-Western: An Examination of Comments on ISIS Counter Narrative Facebook Videos. Int’l Stud. J., 16, 127.

Speckhard, A., Ellenberg, M., Shaghati, H., & Izadi, N. (2020). Hypertargeting facebook profiles vulnerable to ISIS recruitment with” Breaking the ISIS brand counter narrative video clips” in multiple facebook campaigns. Journal of Human Security, 16(1), 16-29.

Speckhard, A., & Esengul, C. (2017). Analysis of the Drivers of Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Kyrgyzstan, Including the Roles of Kyrgyz Women in Supporting, Joining, Intervening in, and Preventing Violent Extremism in Kyrgyzstan. ICSVE Research Reports.

Speckhard, A., & Shajkovci, A. (2017). Confronting an ISIS Emir: ICSVE’s Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter-Narrative Videos’. International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism.

Speckhard, A., & Shajkovci, A. (2017). Drivers of Radicalization and Violent Extremism in Kosovo: Women’s Roles in Supporting, Preventing & Fighting Violent Extremism. International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism.

Speckhard, A., Shajkovci, A., & Ahmed, M. (2018). Intervening in and Preventing Somali-American Radicalization with Counter Narratives. Journal of Strategic Security, 11(4), 32-71.

Thakkar, M., & Speckhard, A. (2022). Breaking the walls: The threat of ISIS resurgence and the repercussions on social media & in the Syrian ISIS women’s camps of the recent ISIS attack on al Sina prison. ICSVE Research Reports.

Weimann, G., & Masri, N. (2020). Research note: spreading hate on TikTok. Studies in conflict & terrorism, 1-14.