Mona Thakkar and Anne Speckhard As published in Homeland Security Today The February 2023 UN…

Exceptionalism at the extremes: A Brief Historical overview of Sweden’s ISIS Foreign Terrorist Fighter Problem

Gabriel Sjöblom-Fodor & Anne Speckhard

Introduction

During the rise and peak of ISIS, the Nordic countries of Sweden, Finland, Norway, and Denmark, stood out as major suppliers of foreign terrorist fighters [FTFs] to ISIS; people who left their homes to fight with or live under the Islamic State of Iraq and Syria [ISIS]. Nearly 6,000 FTFs from Western Europe joined ISIS. Of those people, approximately 300 FTFs came from Sweden, 80 from Finland, 90 from Norway, and 145 from Denmark.[i] Ranked by absolute number of FTFs, Sweden had the fourth highest number of FTFs from Europe, behind only France, Germany and Belgium. Denmark ranks eighth, Norway tenth, and Finland eleventh. Perhaps more importantly however, on a per capita basis, Sweden ranks third of the Western European countries (28 FTFs per capita), outranked by Belgium and Austria. Denmark ranks fourth (22 FTFs per capita), Norway fifth, and Finland seventh. These numbers, alongside evidence that nationals from these countries, particularly Sweden, also joined al Shabaab in Somalia in the mid-2000s,[ii] clearly identify the Nordic region as significantly impacted by terrorist recruitment. Ultimately ISIS attracted over 40,000 foreigners into its ranks, whereas al Shabaab and al Qaeda had attracted only 5,000 or so foreign fighters and very few of these included entire families.

Many explanations and theories have been given for the Nordic contribution to terrorist ranks, which was something both unprecedented and also somewhat bewildering to the general public of these nations. Long known for their stability, generous welfare systems, generosity in taking in asylum seeking refugees, innovation and championing democratic rule and equality between the sexes worldwide, the Nordic’s export of FTFs came as an unpleasant and bewildering surprise to many in government and beyond. Despite their outward generosity and opportunities to immigrants and those of Muslim immigrant descent, there are however push factors existing in the Nordic countries that loom in the background and may form the basis of partial explanations for those who departed to Syria. Now, with the recent terror attacks on European soil and ISIS’s virtual Caliphate fomenting for more such attacks, the question of terrorism and its motivations have begun anew in Sweden, whose potential push factors for terrorism are the subject of this paper.

Sweden in particular, along with the other Nordic countries, has faced a serious dilemma when it comes to integration of their specifically Muslim immigrant populations, and its high number of FTFs to Syria and Iraq. This dilemma of integration was a topic of significant debate during the years of ISIS’s rise to power, both politically and in society, where both terrorist recruitment and Islamic fundamentalism/extremism received widespread attention, and still is. The debates often were circular, with questions such as how and in which environments could these ideologies spread, what was the reason for the high numbers of men and women going to Syria and Iraq, what contributed to it, how should we handle Islamic conservative beliefs that seemed to support terrorist recruitment and much more. We hope in this report, based primarily on field work undertaken during the last year and a half, to spread some light on these issues, including through the unique previously unheard voices of informants from the relevant milieus, who themselves close up witnessed the developments or were active in trying to prevent them, community leaders as well as former members of the radical environments themselves speaking out. What has to be noted also is that the concern of this report is how various phenomena and processes were lived and experienced on a grassroots level among affected populations, communities or groups. It does not concern itself with choosing sides or espouse value judgments.

So in what type of environments were these fighters and travellers formed? What were the contributing factors that made countries such as Sweden have so disproportionately high numbers of FTFs?

Marginalization – history, causes, impact

As pointed out by Speckhard previously, people join terrorist groups to meet individual needs and vulnerabilities which they may find met by taking on the group’s ideological conviction, as a result of indoctrination and/or propaganda, and/or meeting recruiters or other members that give them a sense of belonging, significance, purpose, dream of an Islamic utopia, hope for a partner and so on. Many Europeans interviewed by ICSVE were motivated to travel to ISIS by theologically or ideologically motivated behaviors such as idealism, religious overzealousness, longing for a perceived Islamic utopia or a wish to defend Muslims in conflict zones. Others were suffering from perceived or real discrimination and marginalization in their lives, un- or underemployment, rootlesness, lack of belonging, family problems or other life problems and looking for a livelihood and means to live independently, a sense of purpose and dignity, belonging and identity, heroism, escape, love and adventure and so on.

Indeed, we can confirm that in the Swedish context a sense of marginalization or alienation from mainstream Swedish society, involuntary or voluntary, in many cases has played an important role in fostering an increased risk of extremism and providing a fertile ground in which the Takfiri ideology which ISIS espouses to grow. Takfiri ideology is one in which groups like ISIS accuse other Muslims of apostasy and state that these other Muslims can and should be killed for refusing to adhere to what ISIS espouses as the “true and only” Islam. Takfirism is often referred to as “Salafi-jihadism” or simply “Salafism” in Western discourse, but this can be misleading as most Salafis are apolitical and not in favor of violence or extremism. This alienation has complex roots involving both politics and religion. In a way, it can be argued that the story of radicalization in Sweden dates back decades. Initially it began when the Swedish governments of the 1970-ies and 80-ies adopted a novel multicultural approach towards recently arrived cultural and religious minorities rather than the more assimilationist policies previously utilized in what researcher Eric Kaufmann would call “asymmetric multiculturalism”. The new policies ensured, among other things, minority rights to preserve their specificities aided by government subsidies, etc., reducing the need and demand for integration into wider society, which came to lead to unforeseen problems further down the line as situations and policies changed in unexpected ways. Social and housing policies also led to what has been described as one of the highest levels of housing segregation for minorities in Europe. A Swedish government report released on the 18th of December 2020 states that Sweden has one of the highest levels of inequality between Swedish (mainly white) majority-residential areas and immigrant-majority residential areas related to income, level of education, well-being, and participation in society. Even the ways these residential areas were planned and constructed in the 1960- and 70’s contributed to the problem: the idea was for them to function as small semi-independent ‘towns’, with all the necessary comforts such as supermarkets, libraries, cultural venues and other vitalities locally available, reducing the need to travel beyond the borders of one’s own neighborhood for other than work or leisure. As a result immigrants, including those from Muslim descent, congregated among themselves, go mainly to local schools and can be held back from mainstreaming into society by not only various forms of social cohesion but also poor and underfunded educational systems, with less need or possibilities to learn the Swedish language or learn to navigate the wider national social and cultural customs.

These all form barriers to youth who later may wish to mainstream into society and take advantage of all that European and Swedish society has to offer, resulting in feelings of being excluded and in growing resentment. Close bonds are often built among children who together grow up into youth who begin feeling this sense of exclusion and alienation and sense that their destiny is otherwise–that European opportunities are not for them. When housed in areas with specific ethnic and religious respondents the youth may also find themselves more confined within the strict religious or cultural/ethnic customs of those who try to govern local spaces. Likewise, confined within perceived, if not real, limits of marginalization and social exclusion, in a tight geographic area, some of these youth are easily groomed by terrorist recruiters to believe in an alternate reality in which Islamic governance will afford them opportunities that Europe may never offer. Indeed, we now see that growing up in these environments has provided a feeder chain of youth who would come to form the bulk of the generation drawn into terrorism and extremism in our contemporary times. The strong networks and emotional bonds of togetherness and loyalty in their precarious situations formed among youth who grew up detached from Swedish society came to later be exploited by terrorist recruiters.

While these trends were occurring within marginalized communities, a societal and political shift took place over the past decade in Sweden towards a more collectivist outlook, emphasizing a common Swedish identity bonded by shared values such as beliefs in democracy, liberalism, progressiveness, secularism and gender equality in which minorities have often faced demands to conform in order to be regarded as legitimate parts of Swedish society. There has come to emerge a tension between the notion of freedom of religion and actual religious practice, and that there has been a clear tendency of Swedish media to describe religious pluralism as a source of conflict, with focus on that certain Islamic beliefs and practices are seen as running contrary to the accepted and established norms in society. The researcher and theologian Joel Halldorf, who specializes in studies on religion and modern society has among others pointed out how the Swedish discourse has particularly in this regard of a common identity targeted minority faith communities, usually Muslims of immigrant descent, and in doing so has hardened and become more hostile during the last years. Often pointing out religion, religious people and religious practices as looming threats to society–with a disproportionate focus on Islamic practices it is typically followed by a belief that accommodating them would mean compromising hard-won societal liberties. This occurred while youth were growing up in a parallel society of sorts within their geographic “ghettos”, sometimes having limited knowledge beyond their ethnic, heritage, subcultural and religious identities and failing to feel Swedish or see their Swedish possibilities as they grew into young adults.

The Swedish researcher Eli Göndör describes in his book “Religious Collisions” (2017) how difficult it can be for those hailing from Sunni Muslim-dominated cultures, where religiosity is seen as normal, to navigate the strongly secular Swedish social mores, and notes, alongside others, as well as how antipathically Swedish officialdom as well as ordinary citizens can react to expressions of Islamic faith practices. There is also a statistically proven strong negative attitudes towards Islam and its practices. Indeed, Sweden stands out as one of the most secular countries in the world, and is often thought of as tolerant, yet several studies has shown that the general public tend to hold negative views of organized religion and of Islam in particular. Expressions of Islamic religiosity are often viewed and portrayed as backward and undesirable and statistically mainstream Swedes are likely to stigmatize those who follow them. This of course heightens a sense of isolation and alienation for those coming from Muslim enclaves, particularly women who wear hijab or niqab and men who dress in Islamic style clothes or sport long beards that immediately identify them as practicing Muslims, but also sometimes even ordinary believing Muslims from anywhere. They are seen as nonconforming and problematic residents of Sweden, distrusted and viewed with suspicion by some, but of course not all, in mainstream society.

During 2016, at the height of ISIS power and activities in Europe, and partly against this backdrop, a very unfortunately timed controversy erupted in the country over the notion of “Swedish values”, what constitutes these and the importance of adhering to these to be recognized as a legitimate part of Swedish society. A near similar debate had also erupted in the summer of 2015, when a Kurdish feminist activist stated that her Stockholm neighborhood of Husby was being controlled by ‘bearded shadows’ and religious groups trying to superimpose their values on the local population, instigating a public uproar and a debate that eventually evolved into a debate about conservative Islamic groups and practices (alongside purely ethno-cultural ones), which then got conflated with the more general issue of religious extremism and ISIS recruiment. The debate of 2016 came in part as a response to a controversy in which a Muslim politician would not shake a female reporter’s hand following the controversial resignation of another Muslim member of cabinet (as well as a response to the large influx of refugees at the time and the threat of ISIS). Instead of shaking her hand he placed it on his heart. Amid the public outcry in response he was subsequently forced to resign from all of his political posts. Whether the decisions to oust the two politicians was justified or not is not a topic of this report, but rather how this and following events were interpreted among many Swedish Muslims. While many Muslims would view his action as a sign of respect for his female colleague and sexual propriety, the furious debate that erupted in Swedish society instead focused indirectly or directly on the religious practices and beliefs of conservative Muslims and whether they were compatible or incompatible with Swedish freedom, democratic rule, the rights of women and general norms.

This debate raged for a prolonged period in the mainstream media, civil society and in the political arena and went as far as senior mainstream politicians and even the prime minister himself publicly stating their censure of various conservative Islamic practices, from avoiding contact with the opposite sex to faith-based education. The debate generally problematized, or outright condemned, various religious expressions and practices common among many Muslims, including gender separation in Muslim institutions or mosques, separate bath times for men and women in public swimming pools, the issue of feminine modesty, veiling, visibility of religious symbols, among other things, sometimes followed by comments such as that these practices “have no place in Sweden” or that they needed to be counteracted or marginalized in order to protect Swedish societal liberties. Some of these beliefs or practices publicly criticized or condemned as extreme and reactionary were not even regarded by many Muslims themselves as extreme, but rather as mainstream expressions of Sunni Muslim piety. It was indeed very unfortunate timing. This increased a sense of incongruity or cognitive dissonance among Muslims, as Swedish society is internationally hailed for being open and tolerant, but for Muslim residents these debates was not experienced as Swedish tolerance. It is important to repeat that it is not the aim of this report to establish whether those debates or their conclusions were justified or not, or whether the arguments were right or not, but rather to examine the impact they had on Swedish Muslim communities on a general grassroot level.

During this period, for some Swedish Muslims, seeing their beliefs, sensitivities and religious minutiae regularly subjected to public (usually critical) debate, condemned or ridiculed, it created a feeling that they and their religion were under organized attack, creating a siege mentality and cemented a belief that they were not welcome. “—Those events contributed to the widespread pessimistic feeling among ordinary people in the Muslim communities that a (visibly) believing person could not hope to achieve anything in this country, that there will always be restrictions and limits”, a Swedish Muslim orthodox community leader stated to ICSVE commenting on the period. This aggravated new climate was also picked up by political Islamist and Takfirist figures such as ISIS adherents as well, who pointed to it and incorporated it into their own worldviews as further tangible evidence of a “global war” against Islam and Muslims and that Muslims will never be accepted in Sweden, taking advantage of the situation to promote their ideologies. Various sources with insight into the situations in local Muslim communities during that period heard by ICSVE in addition state that these events in several cases directly or indirectly contributed to the choices of men and women to leave the country to join the perceived utopia in the so-called Islamic State. As many Europeans, including Swedish citizens, who went to ISIS told Speckhard in her interviews with them–they felt they could not practice their Islamic beliefs in Europe and were marginalized, discriminated against and even sometimes, in case of women, assaulted in Europe for modest dress, hijab and niqab in particular. Of course inside ISIS’s totalitarian rule they came to appreciate the freedoms they had actually enjoyed in Europe, but at their leavetaking they believed that ISIS was offering an idyllic state where they could worship freely, follow their Islamic traditions and participate in what was to become an Islamic state utopia.

Segregation, frustrated aspirations, cultural norms and politico-religious interpretations

Besides challenges relating more generally to inequality and other larger socio-economic factors, this sometimes aggressive sociopolitical climate against more conservative expressions of faith and beliefs, and overall lower levels of tolerance to accommodate them by some in Swedish society, has also caused many religious Muslims, conservative, moderate or orthodox, to increasingly keep a general distance vis a vis Swedish society. In most cases, this simply means to focus on family and work while maybe remaining somewhat aloof towards mainstream society. However, in other cases, with those effectively isolating themselves within already separated housing enclaves, many choose to rely more on their community- and personal networks for opportunities rather than on the government or society despairing of help from either.

The topic of segregation, its cause, drivers and impacts have been a recurring topic in Sweden when discussing extremism. In interviews conducted by ICSVE, certain Muslim community leaders or respondents, conservative, moderate and orthodox, state a belief that it is difficult to try to engage with much of Swedish society, either politically or socially, as they perceive that there is a general apathy towards them or maybe even no desire to engage in return. Even as such, it is necessary to mention that on local levels, successful cooperations between civil society and such communities have found place. The new approach taken by some is merely to maintain inconspicuousness vis a vis society. Many thus choose to live quiet lives focusing on work and family rather than engaging with political or societal processes. This sense of alienation was elaborated on by an imam of twenty years who spoke to ICSVE and replying to the question of why some Muslim communities chose to live detached from Swedish society:

”—Some withdraw from society because society does not accept them. It is not because our faith urges us to isolate ourselves, but [because] you are an active part of society within the framework of religio[us beliefs]. It becomes a backlash when some religious expressions are not welcome if you want to be a part of society. Some will not give up their beliefs, and then you will have a situation where they withdraw into the suburbs, do not learn Swedish, and become a burden for everyone.”

Elaborating on this segregation, he believed that many also choose to isolate themselves and reject mainstreaming out of concern to be targeted with stigmatization, abuse or suspicion. In a sense he is speaking about reciprocal radicalization in which those in mainstream dominant society, who have come to fear and condemn those who believe, dress and act differently radicalize by their rejecting and displaying discriminatory behaviors towards the very people they fear.

“—The reasoning is, that society does not accept me, so why should I go somewhere where I will be exposed to resentment and suspicion?” They [Swedes] complain about areas like Rinkeby being a ‘no-go-zone’, but the rest of Sweden is a no-go-zone for many Muslims. They are confronted with so much resentment and nasty looks. Especially women [who dress Islamically] are targeted, people shout at them because they are not scared that they will try to do anything back. How does that feel? What do you think it’s like to be approached by someone who says to you “What the hell is this? What the hell are you doing here?” How do you feel then? This is one of the reasons people keep away, keeping to their neighborhoods. Some cannot bear to take these humiliations, this hatred.”

While the above quote may appear extreme and should not be taken as the universal norm, it nevertheless reflects lived negative experiences of some in their engagement with society, real or imaginary. Likewise many such comments were likewise made to ICSVE director Anne Speckhard while interviewing Europeans who had traveled to Syria to join ISIS.

In a conversation with ICSVE on women’s situations, opportunities and their motivations, an imam in southern Stockholm stated a belief that religion or conservative dress may act as an obstacle to gain entrance to the Swedish labour market, and society.

“—If you wear the jilbab or niqab, what opportunities do you have? Literally zero. Maybe working at a Muslim pre-school or from home.”

This comment echoes a German woman who converted and began to wear hijab. Her employer asked her to leave the workplace and she found it hard to get another job on the same level as before she dressed conservatively. Disillusioned, she left Germany for Syria and ISIS.

What needs to be realized is that those with orthodox beliefs and conservative practices may indeed want to become part of society, but if there is a strong push against them when they adhere to their core beliefs and practices, they do not feel welcome and may choose to instead disengage with the wider society. In fact, if they grew up in isolated minority enclaves, they may even suffer abuse when they do appear in mainstream society and as a result cognitive openings suddenly appear for recruiters of violent extremism,to interest them in violent movements in which they were not ever before interested. When those who wish to adhere to conservative beliefs that are central tenets of their lives experience and believe that in order to become a part of Swedish society, you need to compromise your legally held beliefs and values and also feel under pressure to give these up wholly or in part, many are not prepared to do so, and sadly in some we will see a counter reaction which is not good for Swedish society. This is because violent extremist recruiters are all too happy to exploit this tension in their lives, teaching them that they are rejected and reviled from mainstream Swedish society on the basis of their faith and therefore the only option for them is to adhere to and support groups that will fight on their behalf to establish an Islamic state for them.

What is important to state in regards to choosing to lead these lifestyles of withdrawal, whether motivated by religious or sociocultural considerations, is the social and psychological dynamics that they may create, whether among non-violent orthodox or militant jihadist supporting groups. The groups/communities that practice these withdrawals generally create tight communities where they build their own networks and rely primarily on each other rather than on Swedish society for work opportunities, funding, housing and other forms of support. This may create a sense of ‘semi-autonomy’ within the group making followers feel that they are not accountable to statutory actors, or vice versa, and that societal institutions cannot reach them or prevent their activities, which in its turn may lead to extreme or overzealous behavior. This contributes to the militant jihadist understanding of al-wala’ wal-bara’ (loyalty and dissociation) in which only one’s own Islamic community is embraced and all else is rejected and hated. In some cases across Europe, Salafi preachers have encouraged their followers to reject participating in elections or having anything to do with wider society or statutory institutions which is a lot like other peaceful groups that don’t endorse participation with the government, but extreme Takfirist take this even further preaching hate and violence against Sweden and European institutions that they see as opposing Islam.

In regards to the recent discussions of Islamic ‘separatism’ in France as well as in Sweden, there is an important note to be made. The fact that certain Muslim and Christian religious communities may choose to maintain a distance towards society owing to orthodox beliefs, living inconspicuously while still fully functioning as parts of the same with members working, paying taxes, contributing to development, being engaged in local affairs and so on is a common phenomenon in many countries around the world. In Sweden this is also the case with certain Islamic communities. Choosing to live a lifestyle within the boundaries of one’s faith disagreeing with norms and social mores of mainstream society is a normal phenomenon of many religious traditions, Jewish, Christian and Islamic, and should not unconditionally be problematized as radicalization to any type of violent extremism, although it can serve as a vulnerability to it, when separation is played upon by violent extremist groups.

In this regard, there are a few points to be made on the topic. Followers of some orthodox Muslim movements in Sweden may practice zuhd, a form of ‘pious withdrawal’ from worldly life and from wider society, in order to maintain a type of non-violent ascetic lifestyle centered around worship. This means living a detached life with little interest in the profane world to focus on living in accordance with one’s faith. The level of dedication to zuhd may vary of course from person to person or group to group. Most of those who practice this belief still work in normal jobs and interact with society, but within certain boundaries. In itself this interpretation of Islam and means of dealing with a dissonant mainstream culture is not dissimilar from ultra Orthodox Jewish lifestyles in which they separate themselves from being affected by the secular world by living apart. Similar religious withdrawals from mainstream society are also practiced by Amish groups in the U.S. or indigenous Swedish Christian communities like the Plymouth Brothers or the Laestadians. Terms such as ‘enclavism’ and ‘parallel societies’ have also been used by researchers to somewhat erroneously describe the phenomenon of either zuhd or the general desire to live in peaceful detachment in accordance with one’s convictions.

As such, the practice of either zuhd or more general detachment from society in themselves should not be regarded as dangerous from a national security perspective. Practising these are not signs in and of themselves of harboring potential violent intentions towards the wider society, but they may create other forms of issues, and a common fear raised in Sweden is that they are threats to the general societal cohesion. Yet what is missed with this fear, is the radicalizing effect of being rejected for wanting to live apart and differently from mainstream society. Features among some dedicated to zuhd noted by ICSVE, is having high outward levels of piety, focusing almost exclusively on spiritual matters, maintaining proactive disinterest in society as in social or political trends, sometimes choosing to stay uninformed about current topics, maybe not even reading the news, and avoidance of places seen as morally hazardous to one’s practice of faith. In Sweden, due to the demographic and social situations, those practising zuhd however technically often voluntarily segregate themselves in the vulnerable suburbs with large immigrant descent Muslim populations around the major cities in order to live lives in relative peace and with access to Muslim establishments, like mosques and their congregations, and other faith requirements, like halal food. However, others in the same enclaves as well as those who voluntarily live separated are likely to find themselves excluded from mainstream society if they choose to venture out dressed conservatively or unable to speak Swedish well or otherwise navigate modern secular society, which can then be radicalizing when they feel excluded rather than voluntarily separated from mainstream society. What also must be noted is that both non-violent orthodox groups as well as Takfiri groups that are adhering to ideologies like ISIS, may practice zuhd, and that outside observers may have a hard time trying to distinguish between the two very opposing parties, the former which is simply religiously conservative and the other which is adhering to violent ideologies.

The issue regarding how much religious interpretations and ideology have had a role in fostering segregation, enclavism and violent extremism in Sweden has been a contemporary recurring theme raised by experts and observers. The sense of not being accepted in society seems to play a more significant role in fostering isolationism in certain Muslim groups than religious beliefs or considerations. Another motivation to segregate appears to be a common thread among immigrant communities the world over, more of a desire to preserve cultural, not necessarily Islamic or religious roots, but rather a cultural way of life that in the case of Muslim immigrants is often wrapped up in religious rituals and customs. In this regard Muslim groups trying to preserve their cultural respondents have at time found it difficult in Sweden to achieve this desire to preserve their cultural heritage when their faith is not well accomodated in secular surroundings and in their meetings with mainstream society, even though classical Islamic jurisprudence allows for this. Likewise, still harking back to the country of origin they may cling to religious rulings issued in other national and cultural contexts, making life in Sweden difficult. It may cause spaces where they attempt to with coercion or pressure to uphold the traditions, norms or ways of the old country. A nuanced understanding of how society works might also be lacking due to these factors. This is even more so true for ideological groups, like various isolationist Islamist trends and the Takfiris. What can be said though is that there are a number of religious leaders within the peaceful Muslim community that indeed have advocated a form of separatism and antiintegrationist stances that Muslims should not integrate, that hostility towards the wider mainstream sociey is a virtue, spreading conspiracy theories and political Islamism, breeding isolationism, self-segregation and confrontational attitudes all of which prepare the ground for violent extremists to take it further, with hubs in cities like Stockholm, Gothenburg, Malmö, Gävle, Halmstad, Strömstad and other places. ICSVE was also told about how certain small communities of Caucasian and Central Asian Takfiris are especially prone to isolationism as well as creating their own underground ‘shadow societies’ without any connection to Swedish officialdom.

Al wala’ wal baraa (religious loyalty and dissociation/disavowal)

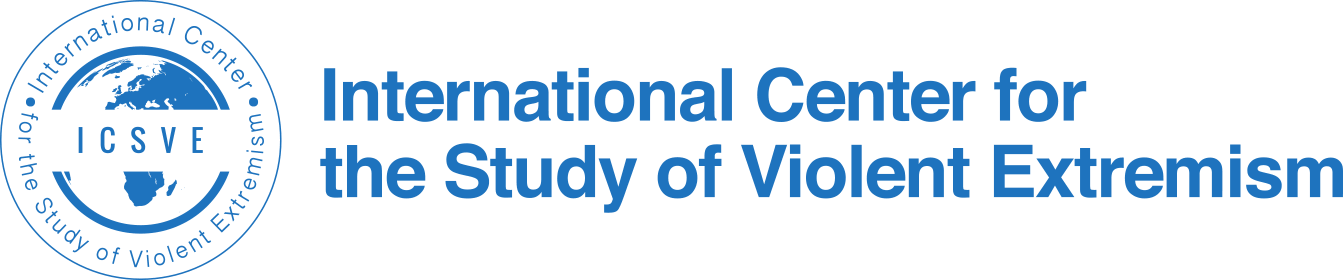

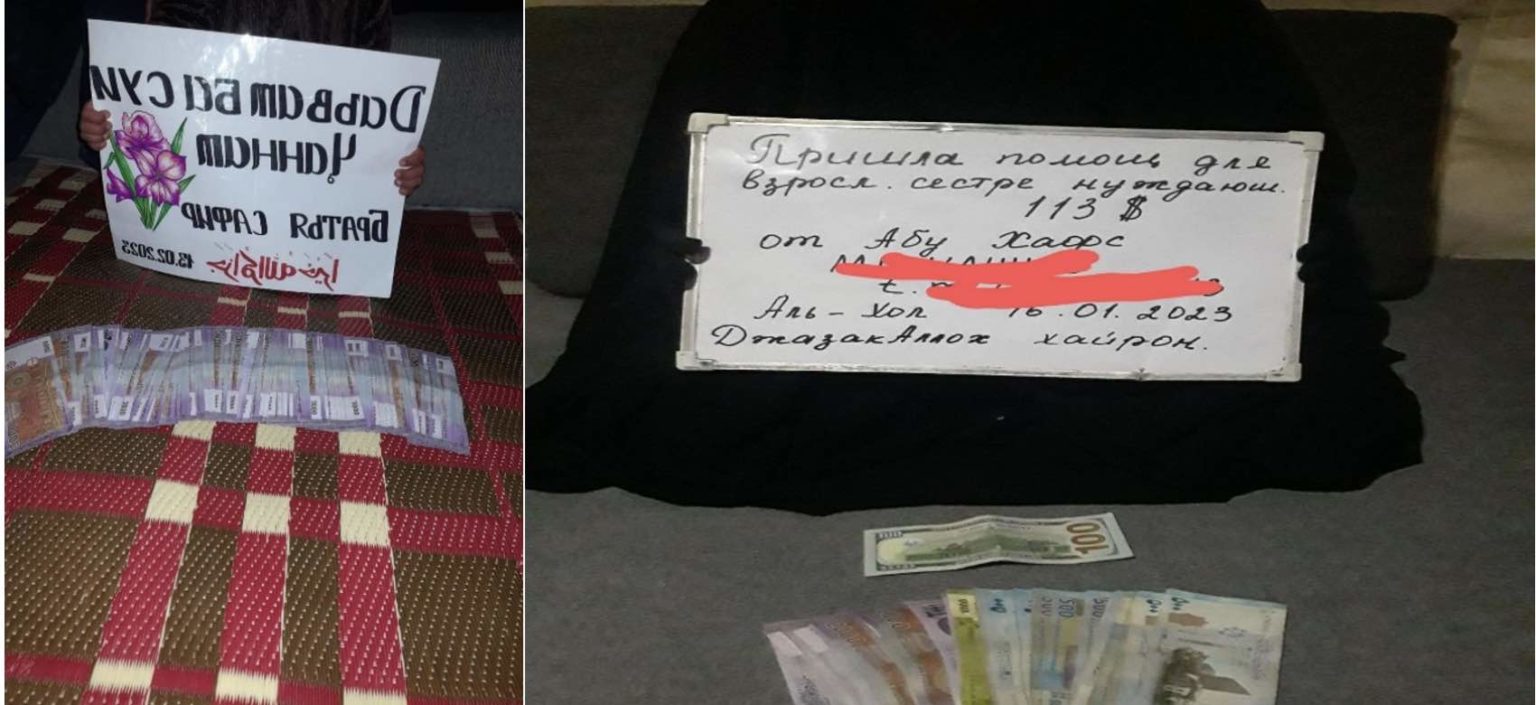

The concept of al wala’ wal baraa (loyalty and disavowal on religious grounds) have been raised. Al wala means to adhere to what the faith approves of, and al baraa means to respectfully disavow and disagree with what the faith does not agree with, this transformed to hate among violent extremists. It basically means to adhere to what is religious permissible and avoid what is not, common to all Abrahamitic faiths. “—Al wala’ wal baraa’ is to disagree but be able to live together, not hostility to the degree that you reject your society and hate people to the degree you cannot be around them”, an Islamic scholar talking to ICSVE explained it. But it seems to account for a lesser reason invoked for isolationism, and only among certain conservative/orthodox or extremist groups, but may account as a main reason for isolationism among Takfiris. The politicized al wala’ wal baraa concept that Takfiris adhere to can however indeed serve as a facilitator to violent extremism, as Takfiri groups claim their highly politicized and violent interpretations are the only legitimate ones, and that the wala’ (loyalty) is to the Takfiri ideology or particular group alone, as all other Muslims are apostates or need to be rectified in their view. The baraa part is then reinterpreted into hostility and hate supporting violence towards anyone outside of their small circles. An informant to ICSVE put it as that among them, the Takfiris are internally very brotherly and generous between each other, but the problem is that this stems from their view that all other Muslims are apostates and that they are the only true believers, so they isolate themselves, even from other Muslims, orthodox or not. The informant had knowledge of such things as Takfiris providing large amounts of money to each other, setting each other up with housing and jobs, and other forms of support, without knowledge or involvement of officialdom or authorities. In many ways this mirrors how ISIS also viewed themselves vis a vis all other Muslims.

Whether motivated by zuhd, al wala’ wal baraa’ or other forms of religiously motivated isolationism, these practices can cause real security concerns besides the social implications they may cause in wider secular mainstream society, if practiced by malicious actors. These communities have often built up their own segregated existences with their own mosques, facilities, economy- and social support, so besides living in worlds parallel to the Swedish societies, it also makes it very easy to hide or go underground if deemed necessary, making it nearly impossible to detect individuals and groups that begin to dedicate themselves to violence against the state. On behalf of ‘the cause’, there can be supporters or sympathizers ready to hide and support an individual and assist him or her to stay away from the searchlights until the heat recedes. Such scenarios are very dangerous, and are likely to be increasingly common throughout Western countries in the future with no more territorial “Caliphate”.

Extreme and political religious ideologies

An issue pointed out by several informants to ICSVE as a driver behind the unprecedented radicalization that took place in Sweden is the various politicized interpretations of Islam that have existed for a long time among certain segments in the Muslim community. The definition of politicized Islam referred to here is the interpretations, mostly developed in the early and mid 20th century, which place state-building and the struggle for political power as central tenents or even the purpose of the faith, breaking with traditional understandings and putting those concerns even above personal piety such as prayer, fasting or charity, and seeing as their mission to restore a lost ‘Islamic honor’ across all walks of life. Indeed, Sweden was one of the countries favoured as a safe haven by Islamist activists and Muslim Brotherhood-members or sympathizers escaping persecution by the secular regimes in the Middle East or North Africa beginning during the 1970- 80- and 90’s. Later, especially after the Algerian civil war, GIA elements would also make their way to Sweden, as well as al Qaeda sympathizers. Some groups following the Suroori and Sahwa trends also had a presence calling to their ideologies, which are forms of politicized activist Salafism drawing heavy inspiration from the Muslim Brotherhood. While the more extreme groups went in their own direction to often preach to their smaller audiences away from public gaze, some of the more mainstream political Islamist groups began engaging with civil and political society. In Sweden, these groups continued their activism in the then still nascent local Muslim communities at various levels, still at the time cheifly consisting of migrant workers and refugees, bringing their ideological outlooks, political savyness and administrative management skills, gradually emerging as community leaders while at the same time politicizing communities under their influence. The then Social Democratic government began acknowledging groups from these trends as ‘representatives’ of the Swedish Muslims around the year 2000, but had cooperated since 1994, consolidating their influence even further. This led to their teachings eventually becoming mainstream in many parts of the Muslim community as they came to control many mosques. Other Islamic, more orthodox trends, like Sufis or purist Salafis, largely became marginalized. A Muslim community respondent of 20 years put it as:

“—If you look at certain Muslim homes and families where people grow up, with their talk and mentality, that you have your specific political worldview whatever it might be, and then superimpose Islam on it, saying ”this is what the religion is about”, is something that easily make people disillusioned, angry and prepared to take measures that are not good, and creates a mindset that is not compatible with your surrounding environments, and this is a problem.”

The nurturing of these political Islamist trends in different forms in Muslim communities can be argued to have laid the broader foundations for extremism among Muslim youth in Sweden. The mainstreaming of political Islamist worlviews and concepts over the years amidst some Muslim communties, along with a popularization of confrontational postcolonial theories, and how conditions in Sweden became interpreted through the lenses of these ideologies rather than the relevant social, political and historical contexts, all came to create among some an acceptance of confrontation and creating a narrative of oppressor – oppression as intrinsic to the faith, having all played an important role. It may also be argued that it serves as a cause for anti-integrationist and confrontative attitudes that have been witnessed and expressed by some Muslims during the last decade. Besides causing an atmosphere of mistrust and frosty relations with mainstream society, the phenomena came to seriously backfire as the war in Syria flamed up. The highly unfortunate situation during the period 2013-2018 of political and societial pressure from mainstream society coupled with the vital political Islamist trends among parts of the Muslim community created a fertile ground for radicalism to violent extremism. These actors, political Islamist and Takfirist, would in various environments and with various modes of expression promote a narrative in which political struggle and power were depicted as central tenents of Islam, and/or that Muslims are victims of persecution by malicious actors, foreign or domestic, in a state of humiliation and degradation, with a need to restore, and if necessary, demand back, lost position or honor. While these groups would promote political activism in various forms they would however mostly stop short of the active promotion of violence, even though some of them maintained ‘tolerant’ or ‘accepting’ attitudes towards radical beliefs and statements, sources with insight have told ICSVE. Their worldviews, narratives, ideologies and rhetoric would however float out into grassroot communities in a decontextualized fashion, popularizing them among many young Muslims but outside of their original contexts, taking on lives of their own. These narratives and rhetoric would come to be picked up by violent actors.

Imams, other religious authorities and laymen ICSVE have had the opportunities to interview who had numerous discussions with radicalized youth noted that in many cases they were already influenced by political terminology and rhetoric they recognized as originating from these influential groups, and that recruiters had simply picked up and utilized these narratives in their process to convince the youth of the message of ISIS. “—The groundwork was already done in many cases (for recruiters to build on)” as an imam who debated several ISIS sympathizers interviewed by ICSVE put it. Another imam of 15 years elaborated on the situation further, stating “—some groups have held sermons in the mosques for over twenty years, Friday after Friday, just speaking about politics, governance in the Muslim world, the need ‘to do something’ and so on. And this (the results) could clearly be seen (during the ISIS years)”. The extent that the preceding political Islamist activism facilitated the spread of ISIS ideology in Sweden needs further research, but should not be underestimated. Indeed it is exactly what al Suri, the al Qaeda ideologue had argued needed to happen to create self organizing cells of uprisings within the Muslim communities globally, in this case uprisings of those who began to endorse and follow ISIS, even traveling there to join the group.

Many Muslim groups emphasize traditional lifestyles with traditional gender roles as a religious duty. When ISIS arose with a Caliphate promising an Islamic utopia in its widespread internet-based propaganda, claiming that conservative Muslims that did not feel at ease practicing their religion in Europe could find a home, some also responded, hoping for the promised utopia and blinding themselves to the reality of the group they were going to join. Blinded in part by these years of preaching that they should be doing so.

Popular and gaming culture

Another phenomena pointed out by informers was that the production and spread of so called gangsta rap in Swedish, by local artists themselves hailing from these troubled neighborhoods, had a role in facilitating the romanticism of violence, violent extremism, as well as the widespread culture of video gaming, which also ISIS made known attempts to imitate in some of their videos. ISIS often appealed to young male gamers telling them they should come to Syria where they could have a real gun and be real warriors, not just avatars in a video game. Likewise, a culture of gang crime was already present in certain neighborhoods, and the possibility to go fighting “for real”, and in what was believed to be a just cause, particularly given Assad’s atrocities, had an attraction to some. An imam talking to ICSVE said “—you would see local kids turning up in Syria with AK47s making our local gang [hand] signs to the camera“.

Physical environments

It is a confirmed fact that the bulk of FTFs and women leaving for ISIS and the Syrian war came from the socioeconomic disadvantaged suburbs, or ‘banlieues’, of Sweden. These are the multiethnic areas with high levels of ethnic and housing segregation and where many of Swedens’ Muslim population have come to reside. They are often plagued by social inequality, reduced access to social and cultural venues or institutions, higher poverty levels, underfunding and underemployment. This could be argued to be as much the dynamics behind the Rinkeby riot of 2010 and the Husby riots of 2013, where large scale rioting erupted initially as responses to isolated events but came to turn into mass expressions of dissatisfaction and anger among local populations over their living situations, as the dynamics behind the issue of extremism in these areas.

Local sources in the Muslim community ICSVE has spoken to, to begin with how the socio-economic disadvataged neighborhoods themselves are a part of the problem. As always it is important to note that it is how the situations are experienced and interpreted, and what effects those interpretations and experiences have, that is of concern of this report in all areas,

”—If you live in these places, you see it very obviously that the authorities are not looking after them,” a local community respondent in the Järva region of Stockholm said.

“—There is trash lying around, it’s generally bad, dirty in various ways, rats running around, no one looks after the neighborhoods. You really get the sense that the government doesn’t care about you if you live here in contrast to those living in the city centre or more well to do areas. The social services also treat people here more harshly than elsewhere”, he argued. He also added the low quality of local schools, where pupils more frequently drop out before higher education, the environment generally being ‘disorganized’ and that there is not enough resources for the young, like youth centers or other meaningful activities. Swedish authorities feel remote and disconnected from the situations on the ground.

“—They speak in an entirely different universe”, another informant said, adding that all the budget cuts to local venues such as youth centers and cultural activities and the apparent negligence and disregard of authorities towards local populations are all acutely felt. Many felt let down by the authorities and the wider society as a whole. It can generally be argued as well that there exist a significant discrepancy between officials and many citizens of Muslim faith, where both sides may struggle to understand the others’ worldviews, viewpoints or actions, if they even come into contact at all. This of course leads to that suspicion and mistrust may arise on both sides.

Another problem brought up is cramped living, with often large families in too small flats.

“—There is no tranquility in the home”, as the community respondent put it, “so the kids go out onto the streets”.

Another locally active Muslim community respondent put it similarly.

“—There is no available housing, you can’t relocate. Take a Somali family of ten living in a flat. Isn’t that a problem? It causes the kids to take to the streets.”

The streets, according to the same and other sources, is where recruiters took the opportunities to engage with the youth, both extremists as well as local criminal actors.

“—Some of the kids here,” another local community respondent speaking to ICSVE added, “if you ask them what they want to do as adults they don’t know. It’s not in the picture. They live on a day to day basis.” A local imam put it as “—Many have their entire lives out here (referring to the highly segregated Järva region of Stockholm but also true for similar areas), they do not have summer houses or cottages in the countryside like the Swedes and may not know the country well enough to find somewhere interesting to go, so they stay out here (in their neighborhoods) all summer and all year if they cannot travel back to their countries of origin or elsewhere for vacations”, which is not that common due to the economical situation of many. Many of course struggle to complete school, get into higher education, into good jobs and eventually succeed, but many also don’t. Sweden is outstanding when it comes to social upward mobility, more so than other Western countries like the United Kingdom, but if you for some reason fail in the system, the challenges and obstacles presenting themselves may be great, especially if you come from certain backgrounds.

All of these factors combined came to lead to the ‘perfect storm’ when ISIS rose and began their call. Indeed, with those who lived dull lives, ISIS suddenly offer all expenses paid adventures with marriage thrown into the bargain.

The igniting spark and its consequences

When the so-called Arab spring spread to Syria, and the situation went from revolution to civil war and Assad’s atrocities against his own population began to spread, it caused a profound humanitarian and religious awakening among Muslims across the West, Sweden included. This provided an excellent opportunity to recruiters. The often horrifying imagery spread amplified by social media evoked anger, pain and fury. Politics and religion became the number one topic in many Swedish Muslim circles, also those who previously had not payed much attention to either. To the recruiters,this was seen as a God-given gift, literally. Thousands upon thousands of awakened Muslims suddenly asked what they could do for their oppressed co-religionists and for their religion, and the recruiters took the opportunity to appear and declare “we have the solution”. They quickly activated themselves to initiate and participate in these discussions on both social media and in real life, usually at local youth centers or at social gatherings, such as barbecues, celebrations, sports events or just friends hanging out, as they often already were part of the friendship networks. Then ISIS swept across Syria and Iraq, conquering more and more land, until they declared their “Caliphate” in 2014, demonstrating amazing successes in battle and in gaining resources that made it look like God was indeed behind them.

The development coincided with an increased social media use by many younger people, with platforms such as Facebook and Youtube becoming popular, both for connection and watching news. At the early stages of the Syrian conflict, so-called ‘internet sheikhs’ began appearing in Sweden, with names such as Michael Skråmo or ibn Mulaykah/Idris Chebawy and several minor ones across the country, taking advantage of technology and the new trends of social media use, to preach and spread their ideologies on their social media platforms, quickly gaining a not insignificant following. Several of them did not really have much religious knowledge either, but they filled a void, sources tell ICSVE. At the time, many regular mosques and imams chose not to address ISIS or its propaganda, a point to which we will return, and the questions regarding ISIS were gathering on a daily basis causing many youth to take to the internet to try to find the answers they were looking for. The increasing numbers of high quality videos depicting Assad’s atrocities and their quick spread, the calls of the nascent jihadi groups (including ISIS) as well as the improving editing skills of propagandists starting to have an impact, caused people to look for answers on why these things were happening to Muslims in Syria and what to do to stop them. The propaganda videos, often edited to either play on religious sentiments, sense of justice, to look ‘cool’ or resemble video games, spoke to segments of the youth living in these marginalized communities or lives calling them to something significant, dignified and purposeful–to save other Muslims, women who were being raped, children gassed to death. Some of the youth, including those already possessing a violence capital and influenced by violence and honor romanticism, found it resonating to both help protect innocent Muslims as well as engage in what was believed to be a ‘just’ war. The videos and speeches began to be shared among people and friendship groups, who would watch and discuss them, and soon recruiters emerged who began encouraging such discussions and also to offer “solutions”. Charismatic recruiters could get many followers, as witnessed by a Swedish imam describing some of the dynamics of recruitment in certain areas or environments, “—there is this thing where everyone knows everyone, and if someone from Angered or Tensta let’s say become extremist, and he was a initiative character and maybe a bit funny and so, kids looked up to him, and then he became religious, persons like that can get quite a few to follow along (in their extremism)”. As noted by ICSVE sources, the aforementioned reoccuring antipathic attitudes in Swedish society towards Islamic religious expressions on both macro- and micro-levels was also exploited by several of these recruiters, by not only encouraging youth to act to protect innocent Muslims abroad, but also as alleged “proof” that Swedish society was in fact at war with the religion of Islam and with Muslims. This was then put into the context of the supposed “global struggle” against Islam by Western interests and other such conspiracy theories.

A local imam in the Stockholm area, who witnessed and also tried to prevent the activities of recruiters, told ICSVE about the methodology utilized by these recruiters. He recounted how especially a flat belonging to one of the prominent recruiters as well as a rented larger facility, both in the area of Rinkeby, quickly became hubs of recruitment and Takfiri activities. They would gather at these locations and also invite people to participate in their activities or to just hang out. He describes how they set out to “win the hearts” of the local youth by “charm offensives”, socializing, organizing fun events, building a sense of brotherhood and making them feel seen and heard. At the same time however, they would “—introduce a lot of emotional talk, like they always do, about global injustices, that we have to act, it is very important, and such very general arguments.” A common recurring question which eventually always came was “—what are you doing for the Muslims? They are raping our women and killing our children and you sit around in Sweden drinking tea. And if you come from these neighborhoods, you might feel “yeah, this is true, I should do this, it is my duty”. At their rented facilities, they would “—hang out all night, chat, play video games, eat take-away food, have “Islamic reminders” and listen to al-Awlaki if they didn’t speak Arabic”, where also individuals of the older generation Takfiris could participate. (Al-Awlaki was an English-speaking internet-based propagandist for al Qaeda, also revered by ISIS, that persuaded many English speakers to join.) The older generation Takfiri-Jihadis were typically members of the infamous Brandbergen community, a small, very radical mosque based in the Stockholm suburb of Brandbergen. Many were hardened veterans of the Algerian GIA or from Afghanistan who collected a small group of devotees around them. Eventually they would begin to drop cues to see who was really “in” and who was not. Those who were deemed “in” were invited to so-called “special sittings”, to further groom them and to eventually pop the question if they wanted to “do their duty”. Already groomed, radicalized in their beliefs, heavily invested in their “brothers”, and seeing no turning back, or no point in doing so, many took the leap to travel, some never to return, either having fallen, or disappeared amidst the general chaos, or to currently be housed in prisons or camps administered by the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) with uncertain futures.

Thus we see that the conflict in Syria, the establishment and subsequent rise of ISIS and the whole atmosphere of the era came to inspire a type of political and spiritual “awakening” among many Muslims, who may not have had much prior interest in faith, stirring a renewed interest in faith, religiosity and politics that was totally taken advantage of by ISIS recruiters. What is important to note is that many who got caught up in these violent extremist movements were not very religious, but could display overzealousness in their faith practice, something which does not equal deeper theological knowledge. They had experienced discrimination mostly based on names, ethnicity and areas of residence rather than visible religious practices and these local grievances could easily be manipulated when ISIS recruiters tried to tell them they didn’t belong in the land of kufr (disbelievers) but should come support the rising ISIS Caliphate. This discrimination and in many cases also inability to navigate Swedish cultural moors had already kindeled a growing frustration and now youth who lacked a sense of purpose, positive identity, significance and dignity were finding it all in being groomed to travel to Syria.

“—Most of those who went weren’t very (religiously) knowledgeable”, a local imam in Stockholm, who worked to prevent travels to Syria at the time said, “it wasn’t usually the tulaab ul ilm (students of Islamic knowledge) who went, but rather the local kids hanging around”. “—Many who went were miskin, newly practising”, another Muslim community respondent in another vulnerable neighborhood explained, “no real religious knowledge, someone who maybe hails from an area like Angered or such and some people they grew up with later became religious, and then those people became their link to the faith, and if those were inclined to violent ideology, so become these people (their friends/followers).

Some who joined ISIS grew up in religious families, others not. With converts however, who in many cases did not experience the isolation or discrimination of born Muslims, overzealousness regarding the religious and morals factors seemed to have a greater significance in the choice to travel. Overzealousness is a common feature with newly practising or converts to Islam, which often entails strictness, rigidity in religious practices, and heightened sense of self-righteousness with a desire to directly address/tackle the perceived ills of the world. Converts often want to prove their devotion to their new faith, and in the case of Swedes who convert, may have rendered themselves rejected from their own families and previous belonging to mainstream society.

To illustrate with a quote from a study by Swedish researcher Ann-Sofie Roald on phases of religiosity among Muslims, she stated “many Muslims tell of how they tended to be emotionally obsessed with the new religion. Furthermore, they wanted to practice every little detail of the Islamic precepts”. A strong ingroup/outgroup dynamic appears, what the scholar Timothy J Winters (Abdulhakim Murad) put as; ”the initial and quite understandable response of many newcomers is to become an absolutist. Everything going on among pious Muslims is angelic; everything outside the circle of faith is demonic”. This of course totally supports the interpretation of the wala wal baraa’ concept that groups like ISIS push. At this stage, the individual will often appear extremist with regard to their worldview and behavior, as the individual only has abstract understandings of their religion, often learning it out of context via books, social media or lectures, and hence, coupled with the zealotry, often try to implement it in a rigid manner in both their own and others lives. Of course this only becomes worse if the teacher is from ISIS or more generally is a Takfiri or otherwise extreme. There is also at this stage a tendency for individuals to become what is sometimes termed a “fantasist”, with unrealistic or naïve beliefs or expectations about life. This is what outsiders and laymen may perceive as radicalization, as the individual are likely to change in their behavior and appearance, displaying the signs popularly associated with radicalization, such as newfound religious zeal, starting to pray or attend mosques regularly, growing a beard or donning a hijab/niqab, and so forth. Also, at this stage, the individual is very susceptible as they are actively striving to learn their new religion and especially if the ‘awakening’ to faith came as a result of witnessing atrocities and injustice; coming into contact with political interpretations focusing on the victimhood of Muslims or Islam and the Takfiri revolutionary narrative of war and insurgency as an integral part of the religion can be extremely dangerous. Commenting on those who traveled, the Stockholm imam stated “—there is this quest for a true Islam, and in most cases you find this in newly practising (Muslims) or converts (to Islam), and in contrast, many who were born into the religion and grew up with it didn’t really go along with this (violent extremism). It’s this recklessness and impulsivity they display, which is based on idealism, ignorance, lack of real life experience and a dream to go somewhere better and make a difference”.

The American researcher Scott Atran has come up with the terms “devoted actor” versus ”rational actor”. A devoted actor represents an individual who has (1) commitment to sacred values, wether religious or secular, and (2) a fusion of personal identity and perception with a collective identity (in Takfirism, the global Muslim community or their own community), and willingness to sacrifice for this identity. In devoted actors, they tend to be immune to material offers, defy cost-benefit calculations (they act because ”it is the right thing to do”), and drive action disassociated with prognosis of success. In Jihadism and Takfirism, this is achieved through propaganda, indoctrination, invocation of religion and a warped sense of justice alongside offering the rewards of belonging, feelings of significance, dignity and purpose. Devoted actors tend to reject offers of material well-being in return for giving up or compromising in beliefs, unlike the ”rational actor” because in their mind their spiritual values are much more important than material benefits or even their earthly lives. This is also why those influenced may be very hard to stop.

Here we can also make the very important distinction between belief-related extremism versus behavior-related extremism in terms of worldviews, behaviors and general practices. A devout believer’s whole world in the Islamic tradition is about pleasing and worshiping God, through the guidance of the Qur’an and the Prophetic tradition. However, if he or she has come to believe through extremist narratives that this goes through terrorism or violence, or that the purpose of the religion is to create and fight for a political entity, then terrorism and the desire to create and fight for the political entity becomes seen as a form of worship, and will be pursued by violence or the support of it, directly or indirectly, as an article of faith. In a secularized world and with desacralized approaches, this concept evades many researchers in the field, and typically ends up being wrongly defined and approached. There is a crucial difference to be made between general, belief-related (theological) extremism, and extremism in behavior and practice. In the West, and especially in the Nordic countries, these two may be conflated. An example would be that a person with behavior-related extremism, such as an overzealous preoccupation with Islamic ritual minutiae, but with otherwise moderate beliefs, will potentially be regarded as a possible violent extremist. This can be erroneous and complicate (or oversimplify) the discourse, so a closer definition is needed.

Belief-related extremism: Extremism in the theological and/or political beliefs of the individual. This would be beliefs such as that the modern terrorism we see from groups such as ISIS is Divinely sanctioned and encouraged in Islamic holy scriptures. Someone with belief-related extremism will usually continually seek ways and means to act these beliefs out; either through physical actions or through implicit or tactical support. This would take its most dangerous and problematic form in the case of adherents to the Jihadi-Takfiri ideology, since they usually believe not supporting the cause equals apostasy and an eternity in Hell, stemming from their belief that these groups are the only ‘valid’ Muslims on the face of the earth. This can become a source of anxiety as they feel they have to keep their work up and this in its turn can lead in the worst case to further violence or the mental collapse of the individual.

Behavior-related extremism: Extremism in behavior, not beliefs. This could be someone who for example continually prays (as opposed to the Prophetic instruction not to tire or bore oneself with prayer), who seclude themselves away from other people, who do not compromise on religiously permissible things, or who is harsh and unfriendly in his or her demeanor. Generally, these individuals harm no one but themselves and tend to burn out. Behavior-related extremism is so strenuous and exhausting for a person, to constantly be aware and pay undue attention to details, that they will eventually leave it, in periods. As for Takfiris, they often cite being ” weak in imaan” (faith) when in a low-period not engaging in behavioral extremism.

In regard to the common term “hijrah” employed by Takfiris both during the ISIS years and currently, there are a few clarifications to be made. In the Takfiri ideology, all current Muslim countries and governments are seen as corrupt or apostates, even countries like Saudi Arabia, Turkey, Jordan, Indonesia or Morocco which are often regarded as ultraconservative or very Islamic in the Western mind but as corrupt and impure by Takfiris. So even if it may be argued from a Western standpoint that they should have relocated to these countries to live a life in accordance with their convictions, they likely did not desire to do so, and to add to it, as Takfiris, they were not likely to be welcomed by the authorities of these countries, on the contrary they were most likely to face arrest, deportation or prison. Rather, the Takfiri call rejects any contemporary Muslim countries in favor of an imagined utopia free from foreign influences which they regard as their divine mission to build and fight for as a political objective, and in their ideological outlook, the ends justify the means. However, in the lingo among Takfiris and also Muslims more broadly, “hijrah” has taken on the meaning of going to live under shariah law, but not in countries such as the aforementioned, but by coming to build the Islamic Caliphate that ISIS proclaimed. Likewise, preforming hijrah is seen by the Takfiris as a way of escaping from the kufr (unbelievers) and thereby escaping the moral challenges faced in Sweden, but the term primarily holds a general non-violent meaning for most Muslims as simply relocating to get away from discrimination and other societal issues.

As ISIS rose, an issue pointed out to ICSVE was that many who were radicalized or affected by ISIS propaganda rejected the news reporting about the violence and abuses of the terror group that began to surface around 2014, believing it to be false Western propaganda against the group and “Islam”. As stated by an initiated source in the Stockholm area to ICSVE, the trust in the Swedish media were in general low among many Muslims, as they already felt targeted by in many cases already referenced herein, feeling that the reporting was biased or angled in an Islamophobic manner. Followers of ISIS themselves promoted this narrative, urging followers or people open to their message to travel down here to “see for themselves” and presenting their own propaganda such as depictions of a peaceful utopia in return. Speckhard found many examples of ISIS members interviewed in prison in NE Syria saying that ISIS told them to disregard mainstream news, that it was all lies and that they should believe those who were actually there, i.e. ISIS sources only. A Swedish source, as well as Speckhard’s research supports, stated that a significant number went as early as 2012-13, before the worst atrocities had become widely known and stated that in several cases the brutality or totalitarianism of the group were not known or properly understood either out of naivety or primarily obtaining information from the biased sources.

The youth association Taqwa Ungdomsförening became one of the central actors in recruitment. They had begun their activities around 2012 and were active in the suburbs around Stockholm, holding conferences, talks and various types of events such as social or sporting activities. One of their leader figures, Idris Chebawy, the radicalized academic, soon emerged as a leader and recruiter in the group. Described to ICSVE as ‘eloquent’ and ‘charismatic’ by people who interacted or observed him, he became one of the more notorious recruiters on the Swedish stage. Sources ICSVE has talked to described the atmosphere in the organization as “accommodating” of radical beliefs and that later recruiters for ISIS and other violent groups were able to move around in its social settings relatively unaccosted and recruit several individuals, among them the young Bilal, whose fate was extensively covered by Swedish media. Several of the group’s followers travelled to Syria while the group itself slowly disintegrated and as of today no longer exist.

The city of Gothenburg stands out as a hub of recruitment to ISIS, to the degree that a senior Gothenburg police officer called the city a “pantry of cannon fodder for ISIS”. Approximately as much as a third of all Swedish FTFs and other travelers to ISIS are believed to have originated in the city, and many of the more prominent and notorious Swedish FTFs were Gothenburgians. The reason Gothenburg stands out as a bastion of political Islamism and Takfirism has a short history concentrated among a few individual preachers who managed to gain a following during the early 2000s. Centering around the organization TUFF (Troende Ungas Framtida förebilder/’Young believers future role models’), they began to spread their message among young Muslims in the region.

When questioned in regard to the strong impact of Takfirism in Gothenburg and western Sweden and what set the scene in the city apart, expert sources in theology as well as other informants identified certain features among the Gothenburg preachers, their messages and followers, namely: a calling (daw’ah) based primarily on activism rather than theology, frequent use of argumentum ad passiones in their speeches rather than referral to Islamic Scriptures, and a different set of socio-cultural dynamics. The activist-based call was described as that in which the western Swedish political Islamist/Takfirist preachers often encouraged “religious activism” above that of formally studying Islamic theology, with a focus on contemporary political issues (such as war in Syria/Iraq, global or domestic injustices, the suffering of Muslims or the

ungodliness of contemporary societies) and the need to ‘act’, rather than undertake formal religious studies or personal piety. Formal mainstream religious scholars were instead often described in derogatory terms such as “palace scholars”, “scholars of menstruation” or “scholars of changing months”, referring to the common political Islamist/Takfirist prejudices that they only focus on religious minutiae rather than wider societal issues, or that “all of the real religious are in prison”. An informant well-acquainted with the western Swedish milieu describes the extremist preachers as “theatrical” in their manners and using emotional rhetoric to a great extent to stir up their listeners’ emotions and zeal. Another theory forwarded was the general left-wing political environment of the city and that the political climate had caused young people to be easily susceptible to the Takfiri narratives of revolutions and struggles against global injustices.

In the city of Malmö, region of Scania, the third largest city in Sweden, the recruitment was handled by a handful of individuals. Many with Takfiri sympathies gathered at a facility in the neighborhood of Rosengård, which functioned as a combined association premise/unofficial mosque. A individual who used to be a part of that circle but later defected told ICSVE that it was a place where people would hang out, hold lectures, listen to anasheed (Islamic acapella music, often associated with Takfiris) and to lectures by the infamous Anwar al Awlaki. Anyone wishing to enter was requested to hand in their phone to be put in a special cupboard. The atmosphere was described as “encouraging” and “accepting” to violent ideology, and news of local people traveling to join the “Caliphate” as being met with enthusiasm and congratulations. The same facility was according to the source frequented by the terrorist Osama Krayem, who the source claims to have run into on several occasions before Krayem left the country to join ISIS and be part of the 2015 attacks in Paris. The recruiters would come and hang out at the facility, socialize and finally ask the target if they “were onboard”. According to this source, some 10 or more men from their circles left Malmö to become FTFs, a number ICSVE has not been able to independently confirm. The facility itself is no longer operating.

Meaning

The recruiters use of tactical empathy with the experiences and grievances of the youth also proved very effective. The combined factors of isolation, feeling unwelcome, frustrated aspirations and rootlessness caused a search for a meaning in life, a longing for purpose and dignity. An imam in Stockholm who talked to young persons in the risk zone of being caught up with ISIS to dissuade them at the time put it as that many have “—the dream of starting over somewhere better, getting away from this place with its challenges.” Swedish society is perceived as too materialistic where life is lacking a higher purpose. The imam elaborated on the situations of many of the youth in his area:

“—They feel alienated, that there are no opportunities available to them, some might even lose the will to live because they see no purpose in life. Then someone comes and says “you can do something good, and go to Paradise.”

In these environments, the role of faith is an important one, both due to the general higher religiosity among Muslims but also for a sense of purpose and meaning in the complex situations many face in Swedish society. A socially active imam in northern Stockholm put it as that

“—It might be the only sacred place left in their lives, Islam and the family. The rest you can perhaps compromise with, but not those two things.”

The feeling of societal rootlessness and lack of belonging is a recurring theme as a pull-factor in Swedish contextes. Feeling that Swedish society does not offer the belonging sought after, some set out to find it within faith. An older Swedish Muslim community respondent from an orthodox community speaking to ICSVE explained it as that at some point, most young Muslims who wish to continue practice their faith (in contrast to those who may choose to secularize, integrate/assimilate or distance themselves from religion) will at one point arrive at a stage, usually in adolesence or young adulthood, where they start asking questions regarding their faith, their own relation to their faith, their place in society and the world, and try to make sense of it all. At this point, some will question and even shun interpretations and practices of Islam inherited from their families or countries or origin, and set out on a quest to find a ‘true’ interpretation of their faith. This is a very vulnerable and hazardous stage, the community respondent explained, as many malicious and violent actors may try to recruit the individual to their own groups. As for why they may listen to such actors, he said “—they speak to them through what is important to them, their faith”.

This tendency to call second and third generation immigrant descent Muslim youth into violent extremism by offering them an Islam very different from their parents is something ISIS capitalized on all throughout Europe. Speckhard for instance found Belgian youth told by their recruiters, “How can your father allow you to live here among the kuffar? He must not be a real believer.” This then drove a wedge between father and son at a time when the son was trying to individuate and create his own identity. The recruiter then set himself up as guide and hero for the son to emulate and ultimately pointed him to his mission to leave the land of the kuffar and go to join and serve ISIS. This story in various iterations occurred all over Europe with youth becoming far more fanatical and devoted to this Takfiri version of Islam than their parents ever were to even moderate interpretations of Islam.

Callers to Takfirism or ISIS would work as well to reach out to the disaffected youth, snaring them with their appeal to emotions, conscience and scripture. In the unhappy, hopeless idle Muslim youth they saw soldiers for their cause, focusing on the second- and third generation Muslim youth who they offered the long sought after sense of belonging, while displaying excessive love and brotherhood. ”—It begins with them buying you pizza, and ends with them handing you guns”, as an imam in northern Stockholm told a group of youngsters in a meeting aimed at preventing such tragedies in a youth community center ICSVE attended at the time. He compared Takfiri and ISIS recruiters with criminal gangs who recruit adolescents to run errands for them, and assured the large gathering that if they fall on hard times, their Takfiri friends won’t be there to save them. Don’t be fooled by them or their rhetoric, he finished.

Yet, Speckhard found a case of a Serbian in Austria who living as migrant worker apart from his family after his father died drawn in exactly by these types of recruiters–offering food, a place to live, a workout community and a purpose that of course traversed through taking on Takfiri ideals and dress and culminating in going to ISIS. Thankfully he was saved by his mother’s intervention.

In their recruitment efforts Takfiris paint a very dark picture of the state of the world and its affairs, another source who had interacted with recruiters during those years told ICSVE. Constant talk of global injustices, Muslims being oppressed everywhere, that the “real” Islamic scholars are all locked up in jail and that Islam is wrongly represented by “palace scholars” who do “corrupt, apostate” powers bidding, that Swedish society is against you, that society is unjust, you are poor and similar arguments, and that it was a duty to “act”. “—You have a very gloomy worldview, that Muslim countries are opressive, Muslims are opressed, and Muslims are misguided in their religious practices, and everyone else is living sinful lives, and there is this quest for a ray of hope,” he said, referring to how individuals adhering to a strict Takfiri worldview perceive the world around them.

A young member of a puritan Salafi group who spoke with ICSVE stated the reasons for youth turning to religious groups, extremist or not, rather than Swedish mainstream society, as being meaning in life, explaining how the dynamics works in the attraction to religious groups.