Mona Thakkar and Anne Speckhard As published in Homeland Security Today The February 2023 UN…

Bringing Down the Digital Caliphate: A Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter-Narratives Intervention with Albanian Speaking Facebook Accounts

by Anne Speckhard, Lorand Bodo & Haris Fazliu[1]

The Western Balkans has been over represented on a per capita basis for foreign recruitment in terrorist groups like ISIS and al-Nusra. Research shows that much of the recruitment into ISIS and al-Nusra, including in the Balkans, occurred via a combination of Internet-based and face-to-face interactions. This research represents an attempt to battle with the ISIS ideology and their active recruitment in the digital space using some of the same methods they do—that is, by interacting with those who like, follow, endorse, and promote their materials and presenting them with counter-narratives in an emotionally impactful video format. Seventy-seven Albanian Facebook accounts (15 female and 62 male) that endorsed or promoted ISIS materials were identified and studied with three counter-narrative interventions. A set of specific indicators, such as the level of engagement with our counter-narratives videos, discussions and engagement on the part of our target audience, among others, served as a measure of our successful online intervention. While it is difficult to ascertain whether our counter-narrative materials had any effect on our target audience in terms of changing their behavior, or reversing their further radicalization into violence, the results demonstrate that it is possible to identify, study, and engage ISIS endorsing and promoting Facebook account holders in a meaningful manner with the stories of ISIS insiders who demystify harsh realities of belonging to the terrorist group and denounce it completely.

Keywords: The Balkans, Counter-Narrative, Defectors, ICSVE, ISIS, Social Media, Facebook, Digital Caliphate, Albania, Kosovo, Macedonia

Introduction

It is estimated that of the 38,000 foreign fighters who have joined Sunni militant groups, such as ISIS and al-Nusra, in Iraq and Syria, upwards of 875 have originated from the Balkans. Of these, almost 800 are reported to have come from the western Balkan countries of Kosovo, Albania, Bosnia, and Macedonia. On a per capita basis (per million of its citizens), these four Western Balkan countries have a higher representation of foreign fighters compared to the four Western European countries of France, Germany, Belgium, and U.K. with the highest per capita foreign fighters (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2017a, 2017b).

To address the growing threat associated with foreign fighters, including the rising fears that returnees may plot attacks in their home countries, many Balkan countries have adopted laws that criminalize recruitment and participation in foreign conflicts as well as introduced strategic documents and civil society programs to address the issue of radicalization and extremism in the country. Local and international bodies have undertaken varying roles in assessing the conditions leading to radicalization, including informing the country’s important national strategies on prevention of violent extremism (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2017a, 2017b).

Despite strong and effective responses on the part of both local and international actors, the current situation remains both dangerous and volatile. Foreign fighters in Syria and Iraq are expected to return home, and some who are not originally from the Balkans may even choose to migrate there, if they find that they can slip in and live under the radar of government and security services. Security officials interviewed recently in the Balkans stated that those who are known to the police would be arrested upon their return and subsequently convicted and imprisoned if deemed a threat to society (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2017a, 2017b). Likewise, law enforcement officials in the Balkans also pointed out that there are others who may have already falsely declared themselves killed in Syria and Iraq, or who will do so, and then surreptitiously return to live secretly without identity documents (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2017a, 2017b).

In the case of Balkans recruitment, groups like ISIS have been relying on a massive Internet-based propaganda campaign and face-to-face recruitment networks to bring the conflict zone to those outside of it. As the primary vehicles of recruitment, their Internet campaign alongside face-to face recruitment have been used to seduce those from the Balkans into travel to Syria, urging them to extend support to their Sunni brothers and sisters under attack from Assad—and in some cases as a form of hijrah (migration to Islamic lands) to help build the Islamic Caliphate and to take part in jihad (holy warfare). In the Balkans, groups like ISIS that arose in the middle of the Syrian conflict have found a fertile recruiting ground, and the ISIS ideology and social support that is provided mainly via the Internet have found resonance primarily in the following individual vulnerabilities and motivations:

- Strong posttraumatic and “fictive kin” identifications with Sunni Muslims being under attack as many in the Balkans remember suffering the same.

- Humanitarian concerns and altruistic motivations.

- High unemployment.

- Material benefits of joining.

- The desire for personal significance.

- Call for jihad and End Times apocalyptic thinking.

- Wish to build and live inside an Islamic “Caliphate” and under shariah law

- The desire and need to keep family ties intact when one member of the family is convinced to go to Syria, etc. (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2017a, 2017b).

While extremists in the Western Balkans who have traveled to Syria include both men and women, they are predominantly male, with women mainly traveling as wives of foreign fighters rather than on their own, although some women have traveled on their own from the Balkans and have taken active roles inside ISIS (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2017a, 2017b). There are also extremists operating on the ground in the Western Balkans who are determined to attack locally, as evidenced by the November 2016 arrests of 19 individuals from Kosovo, Albania, and Macedonia suspected of planning multiple and simultaneous attacks in Kosovo and Albania, including against the Israeli national soccer team during the Albania-Israel soccer match in Albania (The Associated Press, 2016).

With ISIS losing its ability to hold significant territory in Syria and Iraq, coupled with increasing evidence that ISIS is no longer calling for travel to these territories but instead calling for attacks at home, alongside the return of ideologically and weapons trained foreign fighters, the levels of extremism in the Western Balkans may become more of a local problem versus one of foreign fighter recruitment. Likewise, with ISIS, evidence points to Internet-inspired, as well as directed, homegrown terrorist attacks becoming increasingly the norm (Speckhard & Shajkovci 2017a, 2017b).

The ISIS Digital Caliphate and the Need for Counter-Narratives

Since its inception, ISIS has unleashed an unprecedented social-media recruiting drive that recruits in multiple languages globally on a 24/7 basis, resulting in thousands of foreign fighters from more than 100 countries migrating to Syria and Iraq. Despite major military gains in Syria, the virtual “Caliphate” continues to operate. ISIS cadres operating on Facebook, Twitter, Telegram and WhatsApp encrypted and non-encrypted social media platforms have managed to inspire and remotely direct their cadres into action, namely to drive trucks into crowds of innocent people, to plot bombs in airports, and to kill the so-called enemies of Islam. Such attacks have happened in Toronto, London, New York, Brussels, Paris, and Nice—to name a few. Today’s mujahedeen need only a computer and Internet connection to recruit, inspire, and direct terrorist attacks—even continents away.

ISIS is the most prolific terrorist group to date in terms of Internet-based propaganda and terrorist recruitment. Their propaganda net of videos, memes, tweets, and other social media postings cast out over the Internet is designed to ensnare vulnerable individuals and lure them into the so-called utopian ISIS “Caliphate.” The instant feedback mechanisms of social media existing today make it possible for ISIS cadres to immediately swarm in whenever someone retweets, likes, or endorses their materials—to try to seduce vulnerable individuals into their group. In the process of engaging them in conversation aimed at grooming for recruitment, ISIS recruiters find what is missing or hurting in the lives of those they target and offer quick fixes, such as promises of dignity, purpose, significance, salary, sexual rewards, marriage, adventures, travel, and escape from problems alongside promises of a utopian “Caliphate.” They use whatever works to sway their target into beginning to turn over his or her life to serving the group’s goals. In Western Balkans where unemployment is high and faith in government institutions is low, on the ground preachers and ultra-conservative forces spread the vision of an alternative Islamic governance and in the case of ISIS, their Islamic “Caliphate.”

Despite being defeated on the battlefield, ISIS still continues to successfully disseminate its propaganda on the Internet, even though one study suggested a productivity drop of approximately 48% less videos, memes, etc. than produced in the last year (Wing, 2017). The March 2017 ISIS- inspired Parliament attack in London motivated a burst in ISIS related video content. And even before that, even under siege, according to intelligence professionals, ISIS was producing up to five quality recruiting videos per week (Coordination Unit for Threat Assessment- OCAM, personal communication Speckhard, 2017). While we know that ISIS is not calling fighters to travel to the battlefield as it once was, this indicates that their online seduction, which has morphed into calling for more homegrown attacks in places like Europe, remains operational. That said, one could also argue that this only indicates that ISIS is still active in developing recruiting videos and not necessarily that they are unsuccessful in recruiting new fighters and will likely continue to function well beyond their losing territory in Syria and Iraq.

Achieving a complete military victory or a political solution in war-torn Syria and Iraq remains a daunting task. Unless political grievances in Syria and Iraq are adequately addressed, pockets of ISIS cadres will most likely continue to operate underground, migrate to other receptive areas, and continue to recruit via the Internet. In the event of a military defeat, ISIS cadres also stress that they will shave their beards and go underground (Speckhard & Yayla, 2015) as well as move to new safe havens to continue their terrorist activities. Turkey, Libya, Central Asia, and Southeast Asia are all appearing as possible potential new safe havens for ISIS cadres to continue their Internet seduction of others into their ranks.

In 2015, ISIS on average was producing 1000 events per month in a variety of forms in dozens of new platforms and formats. Over half of these products depicted a utopian vision of the Islamic “Caliphate,” namely economic activity, law and order, and the ability to follow ISIS version of Islam and without interference (Whiteside, 2016; Winter, 2015). From September to December 2014, ISIS supporters utilized 46,000 Twitter accounts (Berger & Morgan, 2015). In 2015, each Twitter account of an ISIS supporter had on average over 1,000 followers, which is of a much higher rate in comparison to a “typical” Twitter account (2015). Facebook also had a strong ISIS presence, as did YouTube.

In recent years, Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter instituted aggressive monitoring and takedown policies. Twitter representatives claim to have suspended 360,000 accounts since the middle of 2015 (Twitter, 2016). Jigsaw—Google’s technology incubator and think-tank—takes a different approach by utilizing the so-called ‘’Redirect Method’’ (D’Onfro, 2016; Greenberg, 2016). Once certain keywords and phrases are typed into Google’s search box, links appear that redirect the user to content that is deemed as effectively countering ISIS’ propaganda.

Despite monitoring and take down policies, Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube platforms, unfortunately, continue to be used by ISIS ideologues and recruiters who make use of fleeting accounts to attract and draw followers onto other less controlled social media platforms and apps. These mainstream social media platforms, particularly Youtube, also remain an open space for propaganda videos glorifying ISIS cadres and attacks. Many social media sites fail to detect and take down many of these accounts for weeks, if not months.

ISIS recruiters and propagandists figured workarounds as counter responses instituted since 2014 by Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube (suspending accounts related to ISIS propaganda) went into effect. Just as terrorists morphed their methods when defenses around common targets such as airports, symbols of national significance, and government buildings were hardened, they are likewise morphing their methods in response to Internet- related counter-measures.

On YouTube, ISIS cadres embed terrorist videos into photos, making it more difficult to detect (Mehdi Zograib, personal communication Speckhard, 2017). On Twitter, ISIS recruiters reopen closed accounts within days, if not hours, having figured out ways to migrate their followers to their newly reopened sites. Facebook also continues to host undetected ISIS recruiters, followers, and endorsers whose accounts remain open for weeks, if not months. Indeed, for this study, ICSVE staff were easily able to identify seventy-seven Albanian speaking Facebook accounts endorsing, promoting, and following ISIS in only a few days of searching.

Another of ISIS’ responses to protective measures instituted by different social media companies included resorting to the use of encrypted platforms, such as WhatsApp and Telegram, to attract and communicate with followers. The Islamic State’s presence on Telegram received extensive media coverage following the use of its official Arabic-language channel to claim credit for the November 2015 attacks in Paris (Berger & Perez, 2016, p. 18). Telegram began to suspend it public channels following the Paris attacks, although they still exist in the dozens, and they do not intercept private communications (Berger & Perez, 2016), often claiming they should not be monitored by the platform. For anyone with the skills for monitoring Telegram, it is not difficult to find that ISIS continues to host chat rooms, some that can be easily joined. ICSVE researchers routinely monitor Telegram chat rooms that operate with impunity.

Once ISIS recruiters succeed in seducing a vulnerable individual into endorsing ISIS materials on non-encrypted platforms such as Facebook, YouTube, and Twitter, they contact them, and if interested, quickly move them onto encrypted platforms to bond and move them further along the terrorist trajectory. This practice creates security nightmares for intelligence and police who often find that ISIS supporters they were following on non-encrypted social media platforms, such as Facebook, suddenly go “dark.” Law enforcement and intelligence operators can no longer follow the recruit’s online activities to learn how radicalized they are becoming or if they represent a serious threat. Clearly, it is crucial to intervene while users are still being seduced on the non-encrypted platforms such as Facebook.

As ISIS continues to spread its poisonous ideology over the Internet, recruit others into its ranks, and call for non-sophisticated, but horrific, homegrown attacks, discrediting the group and its ideology is essential. ISIS promoters and recruiters hide in plain sight and operate uncontested on commonly used social media sites. ISIS Internet seduction is most likely to continue to exist, which arguably makes it clear that the second flank in the battle against ISIS is in the digital space. It is now time to mount a strong and resolute digital battle against ISIS. What is needed is to break the ISIS brand by delegitimizing both the group and its ideology.

Counter-Narratives in the Battle Against ISIS

In today’s battlefields, the ability to control meaning and influence thinking is becoming as important as being able to physically dominate the battle space. For instance, this can be witnessed in the spate of “fake news,” carefully released information, and “troll” or information operation attacks on those who dispute the facts that are generated by Russians and other actors seeking to influence elections and populations to be sympathetic to points of view advantageous to them. Although, historically speaking, conflicts are waged in battlefields, in this digital age, memetic warfare—or competition over narrative, ideas, and social media—is becoming as, if not equally, as important.

For these reasons, the current ISIS threat needs to be fought in the narrative space as powerfully as in the physical battle space. Narratives are important to affect thinking and actions. In a similar light, counter narratives, historically used from the vantage point of those marginalized, seek to “empower and give agency to marginalized communities…by choosing their own stories, members of marginalized communities provide alternative points of view, helping to create complex narratives truly presenting their realities” (Mora, 2014). In the fight against terrorist groups like ISIS and al-Qaeda, counter-narratives, often told through the stories of those who have witnessed harsh realities within a terrorist group, are being used to push back against extremist propaganda and recruitment.

There are three types of counter-messaging frameworks or approaches that can be effectively used to counter violent extremism: alternative narratives, counter-narratives, briefly discussed above, and government strategic communications” (Briggs & Feve, 2013, p.6). Government or civil society actors often carry out alternative narrative messaging by emphasizing democratic values and positive social change. In these types of messaging, not much attention and exposure is given to terrorists and their cause. The goal is to “undercut violent extremist narratives by focusing on what we are ‘for’ rather than ‘against” (2013). Government strategic communications refer to government efforts aimed at clarifying government policies, stance, or actions towards an issue. It also includes public awareness activities. Both government strategic communications and alternative narratives can be useful for prevention but are unlikely to reach those already being seduced by terrorist ideologies and groups and thereby narrowing their focus to messaging only from terrorists. Lastly, counter-narratives target and discredit terrorist groups and their ideologies by deconstructing and demystifying their messages to demonstrate their lies, hypocrisy, and inconsistencies. The best counter-narratives may be those coming from disillusioned insiders and not labeled as counter-narratives, so they can thereby slip under the radar of those already consuming terrorist materials.

There is significant consensus regarding the impact of narratives on the individual’s “beliefs, attitudes, intentions, and behaviors,” both for the purposes of radicalization and to fight radicalization, including an emphasis on researching why narratives have resonance for particular individuals (Braddock & Dillard, 2016, p.18; Davies et al. 2016, p. 51).

Researchers have identified four criteria that are important in constructing counter-narratives:

- “Revealing incongruities and contradictions in the terrorist narratives and how terrorists act

- Disrupting analogies between the target narrative and real-world events

- Disrupting binary themes of the group’s ideology

- Advocating an alternative view of the terrorist narrative’s target” (Braddock & Horgan, 2015, p. 397).

Arguably, counter-narratives constructed over the past years have suffered from a lack of emotional impact. For instance, during the last fifteen years, the UK Home Office commissioned websites and groups to argue against al-Qaeda’s use of “martyrdom” and terrorist groups’ calls to militant jihad. Using Islamic scriptures and logical arguments, these groups presented moderate views of Islam but completely fell flat when it came to addressing the grievances that terrorists were so adept at using. They fell flat particularly in the face of al-Qaeda’s, and now ISIS’, use of emotionally evocative pictures, videos, and graphic images arguing that Islam, Muslims, and Muslim lands are under attack by the West, including that jihad is an obligatory duty of all Muslims and that “martyrdom” missions are called for in Islam (Speckhard, 2015). Similarly, although well intentioned, the U.S. State Department’s “Think Again, Turn Away” campaign against ISIS was also heavily criticized. Some critics argued that the messaging campaign relied on recycling ISIS’ violent footage and may have served to “legitimize terrorists” (Edelman, 2014). In this regard, excessive use of violent footage without adequate context (e.g. insider voices) can be equally problematic.

Through our videos, we seek to gain important input and participation from former extremists and terrorists. This is done with the purpose of utilizing their stories to prevent people from joining terrorist groups. They can also be used to generate personalized interventions and prison deradicalization programs, which can prove invaluable, and offering more nuanced and empathetic understanding of the radicalization processes, including radicalization leading to violence.

ISIS’ creative and emotionally evocative use of videos, alongside of their leverage of social media feedback mechanisms, made counter-narratives that are based on logical arguments, versus emotionally evocative counter stories, pale in comparison to what ISIS puts out. The first author of this article has been arguing for years that we must take a page out of al-Qaeda, and now ISIS’, playbook and use emotionally evocative counter stories that are psychologically impactful. Similar to Madison-avenue marketing, we need to target the ISIS brand while creating better ones.

The most effective tool to discredit both ISIS and their militant jihadi propaganda is to raise the voices of disillusioned ISIS cadres themselves (Speckhard, 2016; Speckhard, Shajkovci & Yayla, 2017; Speckhard & Yayla, 2015). While former extremists have been used effectively in doing CVE work, problems exist in working with defectors and formers, including issues of trust and reliability. Some formers find it stressful to speak about their experiences and others simply refuse. Some cannot be trusted as they vacillate in their opinions about the terrorist group to which they formerly belonged or endorsed. Moreover, many are not psychologically healthy—having been seduced into the group because of psychosocial needs they hoped the group would meet. After serving in conflict zones and inside a horrifically brutal organization, some suffer from posttraumatic stress and substance disorders, making them also unreliable interlocutors and questionable role models (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2017c).

The safest option would then be to bypass using formers in face-to-face interventions with vulnerable audiences and instead capture defector voices on video, as video testimonies can be better prepared and controlled. There is no danger of the defector saying anything off message in an edited video, as his or her testimony denouncing ISIS is already pre-vetted and set. In addition, a video interview of a defector denouncing the terrorist group he or she once served can be dispersed widely, whereas an actual defector is limited in time and space. He or she may become fatigued and emotionally distressed and may have to be supervised by a controller who accompanies her or him.

The U.S. State Department announced its support for raising the voices of ISIS defectors against the group in its May 2016 Department of State and USAID Joint Strategy on Countering Violent Extremism:

“The GEC [Global Engagement Center] is coordinating interagency efforts aimed at undermining terrorist messaging … under taking strategic campaigns to highlight the hypocrisy of ISIL’s messaging, for example, by amplifying the voices of disillusioned former fighters, family members, and victims of terrorist attacks. (U.S. Department of State, n.d.).”

Despite State Department’s ambitious goals and efforts, including those of the UK Prevent team, the truth is that while ISIS issues and makes use of thousands of recruiting videos, memes, and tweets on an ongoing basis, there is little compelling online content countering them. What exists is mostly cognitive versus emotion-based compelling content. What is needed is a strong campaign to first break the ISIS brand and then replace it with an alternative that redirects the frustrations and passions of those facing emotional, social, and political problems, and who are angry over geopolitical events that resonate in their own lives to nonviolent solutions.

Breaking the ISIS Brand – the ISIS Defectors Interviews Project

The International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE) team have spent the last two years capturing ISIS defectors, returnees and ISIS cadre prisoners’ stories, most on video, in their Breaking the ISIS Brand Counter Narratives Project. Thus far, ICSVE staff have collected 71 stories of defectors, prisoners and returnees and twelve of parents of ISIS fighters from Syria, Iraq, Central Asian, Western European and the Balkans. From the ISIS emir who admitted that ISIS “was wrong” to the Syrian girl who hoped to become a doctor but instead became an ISIS torturer, ICSVE staff have managed to capture the voices of those who described the horrific realities of life inside ISIS.

Eighteen short counter-narrative video clips have thus far been produced from the longer videotaped interviews. The interviews are edited down to their most damaging, denouncing, and derisive content. The Breaking the ISIS Brand video clips are made to be emotionally compelling to denounce ISIS. Equally emotionally evocative video footage and pictures taken from actual ISIS content are added in to graphically illustrate what the defectors are narrating—to make their stories come alive and to turn ISIS back on itself. The defectors are asked at the end of their interviews to give advice to anyone thinking of joining ISIS—a time when most of them strongly and emotionally denounce the group and warn others of the dangers and disappointments of joining.

The finished video clips are named with pro-ISIS names and start with an opening screen that mimics ISIS propaganda materials, or is actually taken from ISIS propaganda materials, so that those already engaging online with ISIS propaganda will be likely to also encounter our counter narratives and get a very different message. Our video titles are modeled based on our knowledge of key words employed by ISIS followers online. Such terms/verbiage were built into our counter messaging videos to ensure higher ranking of our video materials in search engines as well. The video clips are being subtitled in the 21 languages that ISIS recruits in on a 24/7 basis, such as Arabic, French, Dutch, German, Uzbek, and Russian, and then once produced, the videos are uploaded to the Internet with the hope of catching the same audiences that ISIS is daily recruiting on a 24/7 basis.

Currently, ICSVE uploads the video clips to the ICSVE YouTube channel and relies on a process of chance for accessing the counter-narrative video clips posted there. Western press has covered them, and we have evidence that they are viewed given the many comments that they receive. A Syrian ISIS defector in Turkey told us that one showed up on his Facebook page. We know of another being viewed by a security professional monitoring an ISIS Telegram chat room.

We also know that the police in Kyrgyzstan have posted them on their website and used them in CVE prevention work, as have other NGOs in Kyrgyzstan. Similarly, the Dutch and Belgian police recently trained on their use. Jordanian religious CVE workers (al Hayat) are using them in trainings. The video clips have also been focus tested in face-to-face groups with target audiences in Jordan, Kyrgyzstan, Kosovo, and the United States, including with hard-core jihadis in Iraq and Jordan, with positive results. The videos also led to animated discussions that allowed for a good diagnosis of radicalizing factors among the target audience as well as reflecting evidence of influencing participants negatively against ISIS. We also focus tested them with teachers, police, intelligence, social workers, and CVE professionals in Kyrgyzstan, Kosovo, Belgium, Iraq, Jordan, the Netherlands, and the United States, all with positive reception as a useful prevention tool. In Iraq, we focus tested two of the videos with an ISIS “emir” held in prison, who, after viewing the videos, evidenced a shame response and admitted that “we [ISIS] were mistaken” (Speckhard & Shajkovci, 2017c). We are also aware of a young teen in London who was put off from traveling to Raqqa after being shown one of our videos.

For this study, we decided to see if we could take these offline results of the video clips to the digital space to fight with ISIS online recruiting. This required finding out if we could identify ISIS endorsers, followers—and even recruiters—on the social media accounts we chose to study—in this case Facebook—and target placement of the videos on their social media accounts. The central guiding question of our research was as follows: Can we identify ISIS endorsers, followers, and promoters on social media? And if so, how can we infect their accounts with counter-narrative materials, and to what effect?

With regards to the first part of our research question, we already had some evidence that it was possible to reach ISIS endorsers, followers and promoters in the digital space as our ICSVE staff were already monitoring ISIS on Telegram channels. However, for this study, we primarily went after Facebook accounts. We also had confidence about reaching the target audience based on work by Frenett and Dow (2016) and their Moonshot group (working with Google’s Jigsaw) who recently reported their findings of doing an intervention study on Facebook with ISIS endorsers. Their study led them to conclude that those who wish to fight against terrorist groups can reach the same digital audiences that terrorists do to intervene in various ways, including to pitch them counter-narrative materials.

We know that ISIS is adept at using the feedback mechanisms of social media, and we wanted to learn if we could use their same methods against them. Social media is an adaptive and two-way road, meaning terrorists are not the only ones who can access social media to influence extremist thinking. Those seeking to counter terrorists messaging can also make use of social media to fight them.

Methodology and Research Design

Given the novel type of research involved, our general research design was exploratory in nature. Three approaches were used to explore the digital environment on Facebook, each developed in succession of the previous one. Our goal was to identify the most suitable method to counter ISIS’ ideology on Facebook and to learn if our counter-narratives could make a positive impact that we could measure, or at least observe.

Facebook was chosen for three reasons. First, Facebook serves almost 1.5 billion people globally and enables an extensive outreach to people in the whole world. Second, Facebook is a valuable resource for researchers as it provides a significant amount of personal data that can be utilized for various research projects, such as this one. Lastly, Facebook is a popular social media platform used by terrorist groups, aka “Media Mujahedeen,” who disseminate ISIS propaganda on a 24/7 basis. In this regard, Facebook represents a suitable social media platform to conduct this intervention.

The content of ISIS supporting and promoting accounts were coded based on the following:

Expressions of Radicalization: Given that this was an online study, it was difficult to engage in a critical and empirical evaluation to identify with utmost certainty individuals at risk for radicalization or terrorism. In practice, it would be difficult, regardless of the tools used, to effectively assess the level of extremism or a set of social, psychological, or other predisposing vulnerabilities of our target audience just by researching online. Establishing the true identities of account holders is also not an easy task, if not impossible in many cases. While we took all expressions of radicalization at face value, we were also cognizant of the fact that law enforcement officials, journalists, and others may be posting with fake Facebook accounts, pretending to be radicalized individuals to conduct similar investigative work and not actually represent radicalized persons at all. In addition, a recruiter may have created multiple Facebook accounts to spread ISIS ideology. In this regard, multiple accounts may not necessarily represent many persons, or the persons they appear to be, but instead represent the same ideologue behind many accounts or a counter-terrorism researcher, police, or journalist. The case may also be that accounts were created to impersonate someone following their arrest or death.

As the aforementioned were difficult to verify or deconstruct, for this study, we simply took all account holders at face value and assumed if they were liking, sharing, posting and endorsing ISIS materials, then they were indeed representing radicalized individuals and in a one-to-one ratio. Such materials included:

- References and glorification of ISIS battles in Iraq and Syria.

- Interpersonal communication related to ISIS and ISIS-related activities.

- References to ISIS and ISIS ideology including distributing their propaganda materials.

- References made against the West in support of ISIS.

We found many accounts that openly denounced Western involvement in Iraq and Syria. Such account holders in many cases expressed extremist worldviews. However, the focus of our research was specific accounts and imagery that indicated open support for ISIS and ISIS-related violence and in the extreme case disseminating ISIS related propaganda on behalf of the group. Only those that fell in the latter group were included in our sample of those who we deemed as appropriate for a counter narrative intervention. We could not determine whether the account holders were who they claimed to be. However, after studying their online behaviors we could determine that a counter narrative intervention would be appropriate.

Equally important, while we found a considerable number of accounts clearly communicating support for the terrorist group, it does not necessarily mean that such individuals will resort to violence. The path towards terrorist violence is more complex, individual-specific, and requires a variety of triggers. While it is often difficult to detect when an online person shifts his or her position towards supporting ISIS—that is, how individuals exhibit radicalized behavior on social media—we also considered whether our target users shared material from known pro-ISIS accounts. Lastly, we made an attempt to distinguish between serious ISIS supporters and endorsers and casual chatters, often referred to as “white noise,” which may be considered irrelevant and extraneous information collected by just browsing the Internet.

Indicators Used to Measure Success

To ensure that we reach our intended audience, the authors relied on a stringent research design, outlined further below, and expert verification. The following indicators were used to measure the success of our intended objective:

- Identifying accounts that displayed measurable indicators of radicalized behaviors such as liking, sharing and distributing ISIS content

- Engagement of such accounts with our counter-narrative videos.

- The extent to which our counter-narrative video materials were endorsed or shared by our target audience, as measured in terms of “likes” and “clicks,” or views.”

- The extent to which counter-narrative videos led to engagement and discussion on the part of our target audience, showing that the material made them “think again and possibly turn away,” to borrow a tagline from the recent State Department’s counter-narrative campaign.

Desired but not verified indicators included:

- The extent to which video materials led to prolonged and sustained attention to the material.

- The extent to which the videos created a real behavioral change in the online target audience, causing them to turn away from ISIS and its ideology.

- Although videos might have led to active disengagement or cognitive opening, we did not have the resources to offer offline support for those repelled by ISIS to redirect them to healthier alternatives nor do we have examples from this study of someone from the target group seeing offline intervention (e.g. by reaching out to the producers or others to ask for more critical information to discuss the content further).

While it is difficult to measure the exact success of our online counter-narrative intervention with precision, we do know that we successfully were able to identify and reach our target audience with compelling counter narrative materials. How well our counter-narratives resonated with our target audience and caused them to be disgusted by ISIS is not easily measured, but we could observe that they caught the attention of those who received them and caused considerable discussion. Thus we consider a success if our video materials could even reach (i.e. awareness metrics) to individuals who are already moving dangerously along the radicalization and terrorism trajectory. Any engagement with our video materials on the part of account holders who appear to represent serious ISIS supporters and promoters, can be considered a measure of success given that at that point on the radicalization and terrorist trajectory they will have narrowed their focus only to material coming from ISIS. Such individuals will likely only be knocked off the terrorist trajectory by hearing and taking seriously denouncements from those who were inside the group—which is precisely what our counter narratives contain.

Sample Selection

Our general research design was exploratory and experimental. Over a relatively short period of two weeks in February of 2017 and one week in September 2017, we identified accounts that openly supported or endorsed ISIS or ISIS activities, or even distributed their content. In some cases, sampling was conducted by setting up anonymized Facebook accounts and identifying Albanian speaking radicalized individuals through searching for certain keywords in Albanian or Albanian with Arabic references and jargon on Facebook, such as ‘servant of Allah’, ‘soldier of Allah’, ‘khilafah’ [caliphate], etc., and then friending these accounts. As initial accounts were identified, the snowball sampling method was then utilized. For instance, once a ‘radical’ account was identified, the friends list was searched for similar accounts and likewise added to the sample. An Albanian-speaking sample was quickly put together in a matter of two weeks consisting of 77 Facebook accounts (15 female and 62 male) that endorsed or promoted ISIS materials.

A number of our Facebook users in our sample claimed to be operating out of Albania, and most, based on their postings, appeared to reside in the Western Balkan countries of Macedonia, Kosovo, and Albania. That said, it is difficult to establish the natural origin of the account holders; therefore, we identified such accounts on the basis of language spoken (e.g. Albanian). We could not specify with certainty the country of origin (e.g. some might be hiding behind a VPN machine), with the exception of some cases when some other available information was drawn from the accounts of individuals (e.g. by looking at their network list). Given that our researchers relied on the snowball sampling technique, they first followed original accounts and then their network of followers, and so on. This is not to say that our snowball technique captured the entire network of Albanian ISIS supporters and endorsers on Facebook.

Criteria for the accounts included in the sample, (which we treated as individuals whether or not they in fact were actual persons) included posting and endorsing ISIS materials. These criteria were used to decide if an account represented a “radicalized” individual applicable for the study. While we took all expressions of radicalization at face value and assumed if they were liking, sharing, posting and endorsing ISIS materials then they were indeed representing radical individuals and in a one-to-one ratio we were also aware as mentioned earlier that might not be the actual case.

Similar to other research conducted online, it is often difficult to authenticate the identity of research participants. Some could argue that more evidence is needed to authenticate our target audience. In other words, more evidence might be required to show that we were actually able to reach the individuals at risk for violent radicalization and not some other users, especially if recommendations for CVE are being made. While researchers may employ a number of measures to authenticate participants online (e.g. email registration, bank account numbers, etc.), such measures could not be applied in the context of this study. Likewise, the researchers are aware of the complications in verifying identities of our target audience, especially in light of possible law enforcement activities online. Although important and desirable, the authors felt that it was not necessarily critical to confirm the actual identity of the target audience as the focus was on the collective behavior of our target audience.

Intervening with Radicalized Individuals

This experimental research design allowed for testing whether ISIS defector video clips might have an impact on individuals whom we identified based on their Facebook accounts as supporting or promoting ISIS. The approach was comprised of four steps. In those instances when a direct relationship with our participants could not be established, the first step included setting up four anonymized e-mails and Facebook accounts (male and female) and identifying radicalized individuals by searching for certain keywords on Facebook, such as ‘servant of Allah’, ‘soldier of Allah’, ‘khilafah’ [caliphate], etc. A list of criteria, explained below, including posting and endorsing ISIS materials, were used to decide if an account represented a radicalized individual and were applied to the accounts that came up in search to create a sample. Next we began “friending” such accounts with all four of our accounts.

Using multiple accounts was deemed necessary in our design as our goal was for all four of our accounts to friend everyone in the sample. This was important in the event that some of our accounts ended up being “unfriended” or blocked, particularly those posting ICSVE’s counter-narrative videos, in which case the other accounts could continue to observe and record the results. However, the sample did not come together in this manner as some accounts accepted one or more of our anonymized accounts friend requests, but not all, sometimes due to the gender of the anonymized accounts. More accepted the friend requests of our female anonymized accounts than those made by males. As our accounts and those we were studying were being taken down on a daily basis, we had to move ahead with the “friends” we had and assemble our sample without all four of our accounts becoming a friend of every account in the sample.

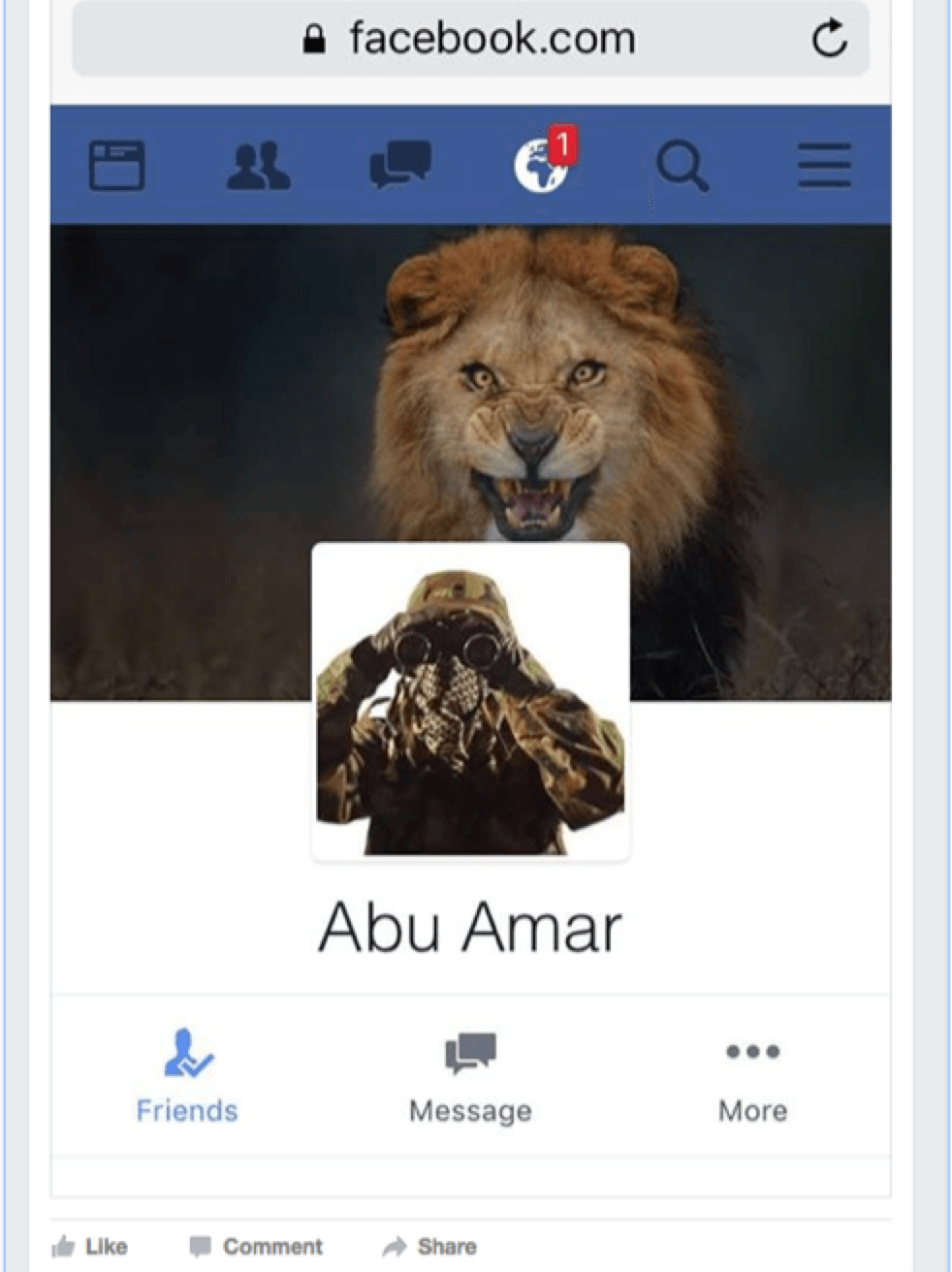

The authors found it necessary to have female profiles due to the fact that most of the radicalized women do not accept friend requests from male profiles. A considerable number of male subjects also did not accept friend requests of those having a female on their friend list, which is deemed by such radicalized individuals as forbidden due to the “likelihood” of being tempted to have inappropriate thoughts. For our male profiles, photos of lions and soldiers (that have no link to any military or terrorist group) with balaclavas were set as profile picture. For our female, a woman in a burqa was set as the profile picture.

To measure the impact of the intervention, a radicalization matrix was developed for the purpose of determining the “degree of radicalization” within the sample. In this regard, in this particular step, posts, comments, shares, and likes were used as engagement metrics. If posts, comments, shares or likes endorsed ISIS’ ideology or actions, then the metric was coded as 1 (“yes”), otherwise they were recorded as 0 (“No”). In addition, a confidence metric was established to measure the confidence of the researcher. The confidence metric was solely based on the amount (numbers) of evidence of these incidents of liking, posting, and sharing of ISIS materials (all captured in screenshots). The more evidence, the higher the confidence, and vice versa.

The third step involved the intervention itself, which was planned to be three video-uploads of the ISIS defector counter-narrative video clips under the following titles The Glorious Cubs of the Caliphate, A Sex Slave as a Gift for you from Abu Bakr al Baghdadi, Join or Defect from ad-Dawlah? Additionally, the sample was tagged in the video to garner attention and the post was made public so that the video could reach more viewers—(i.e. also appear to the friends of the sample). Additionally, the sample was tagged in the video to ensure that the sample participants saw and hopefully watched it. The last step was to involve an analysis of the intervention.

In this approach, in less than a couple of days, we were able to reach a sample of 77 Albanian speaking Facebook accounts that endorse, follow, and share ISIS propaganda who we deemed to represent radicalized individuals sorely in need of any type of intervention to move them away from terrorism. The study turned out to be quite dynamic; the moment we started our intervention with such users, we found some of our accounts were disabled by having our accounts unfriended as we had expected. That said, we had the opportunity to observe many responses to our materials as reported herein.

Data and Results

An Albanian-speaking sample consisting of 77 Facebook accounts (15 female and 62 male) was put together in a matter of days. Based on their profile descriptions, their ages ranged from 13 to 51 years old. All of them endorsed or promoted ISIS materials. Thirty of the 77 accounts were rated as highly radicalized based on their high activity in liking and posting/sharing ISIS material, and two of them claimed to be in Syria fighting for ISIS. One such account was tied to a 13-year old boy in the sample. He identified himself as an Albanian-speaking boy inside ISIS in Syria. The rest were moderate to low-level followers and endorsers, but by no means ideologues.

During the course of studying these accounts over a two-week period, more than half of our sample disappeared as a result of Facebook’s takedown policy, resulting in a sample of only 31 accounts to which we were able to apply our intervention. The thirteen-year-old in Syria’s account was one of the accounts shut down in the beginning of the study.

These 31 individuals that remained in the sample were subject to critical analysis examining their posts, comments, shares, and likes to identify links to ISIS support. All the participants in this sample had shown support for ISIS in one way or another, such as liking ISIS content, posting ISIS emblems, commenting in support of the organization, posting photos of al-Baghdadi or those of ISIS soldiers, sharing news from ISIS media (Amaq), sharing photos of ethnic Albanians foreign fighters in ISIS, and other ways of endorsing their content. Twelve of the remaining 31 accounts were rated as highly radicalized, with the rest as moderate to low-levels of radicalization. Some of the profiles tried to disguise their affiliation by not mentioning the word ISIS, caliphate, or khilafa, however, an analysis of their likes and social networks yielded different results. In other words, nearly half of the profiles were considered – with high confidence – as highly radicalized.

The main research question of this research was to learn if online counter-narratives could be targeted to Albanian speaking radicalized individuals, and if they would have any effect. We learned that we could not only easily discover and communicate with radicalized account holders, but could also, in the very short-term, reach them with our counter-narrative materials. In doing impact analysis of our intervention, in a number of cases, we managed to lead our target audience towards constructive engagements. That said, given that this was a relatively short intervention online, we were unable to establish any prolonged engagements or determine the extent to which we have achieved behavioral change in such individuals. Whether the members of our target audience reached out to other service providers for direct treatment also remains unknown. On a positive note, in the instances where we achieved constructive feedback on our posted counter narratives, we will continue to nurture such relationships, ideally leading to more sustained engagements—and ultimately achieve behavioral change.

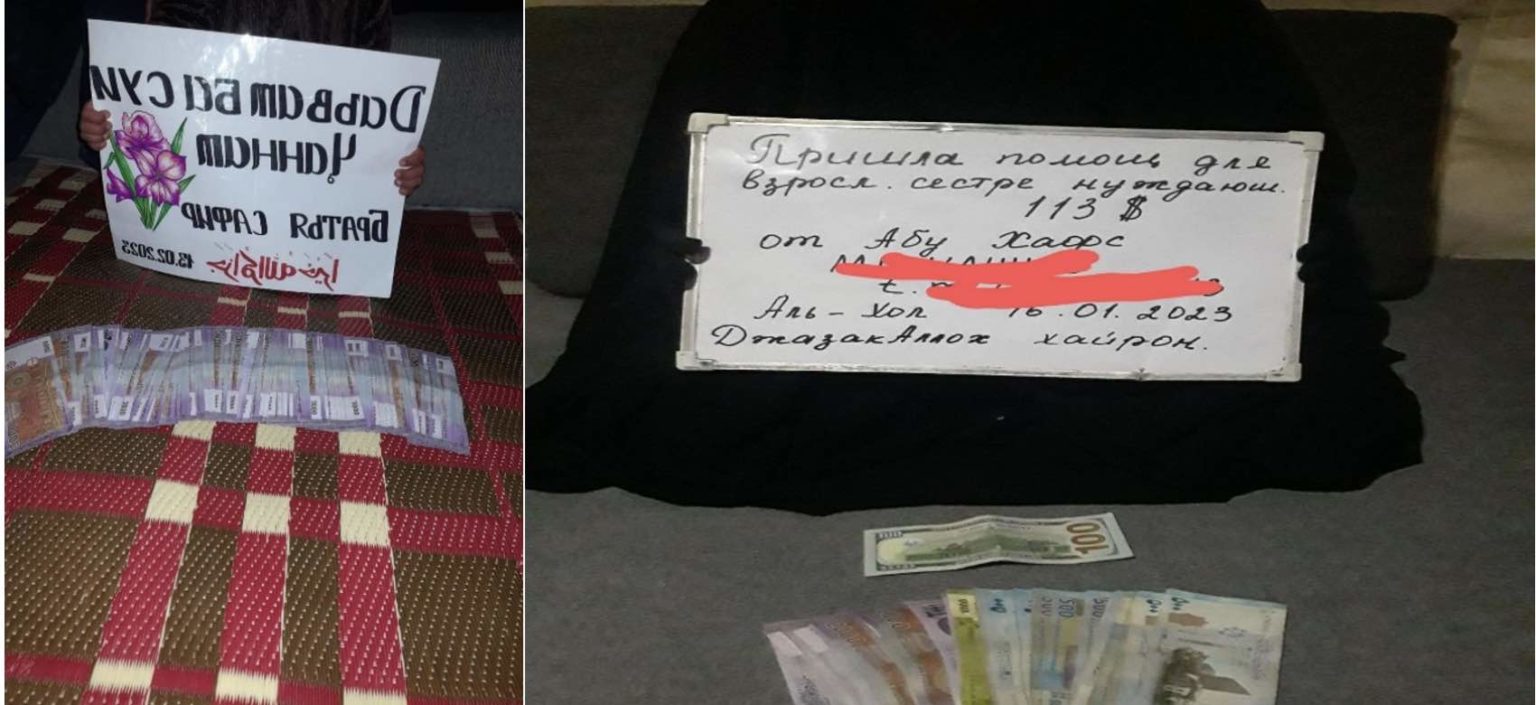

Disabled and Hacked Accounts

In those cases when anonymized accounts were used to carry out our research, we learned that as we began our counter-narrative interventions online and as ISIS supporters came to realize the purpose of our online activities, our counter-narrative posting account was very quickly unfriended. They also called us names and made threatening remarks. Likewise, we found that as we were doing background research, their accounts also disappeared, as Facebook was taking their accounts down as well. This reduced our total sample from 77 to 31. In the first week, two of our accounts were disabled either by being hacked or taken down by Facebook on their own initiative. The first of our anonymized accounts to be taken down—three days after it was activated—was the female account. The second account, named Abu Amar, was the male who posted our counter-narrative videos. His account was taken down a few hours after the third video was posted, making it difficult to observe the long-term results of our interventions.

Infecting ISIS Recruiting Territory

With our online intervention we learned that it is possible to not only discover radicalized profiles of ISIS supporters and propagandists, but also to engage them with counter-narratives. We also learned from the views and share functions of Facebook that our videos were clicked on and watched, shared, and even endorsed, It is difficult to estimate the extent to which our video materials caught the full viewing attention of our target audience, however. The collected statistics on comments/likes and views indicates a trend of increased interest in our videos, however—most likely due to a tagline was added on the second video that likely piqued more interest. The first video received 46 views within 24 hours of posting it whereas the second received over 270 views in less than 24 hours. Within the 24 hours of posting it, the second video reached 320 views. Due to the interest in the second video, several account holders started viewing the anonymized account profiles of the researchers and watching the second video, which most likely explains the increase in viewership from 46 to 80. There were more comments added to the video as well. Comparatively speaking, the third video had 140 views only a few hours after it was posted. In total, we know with certainty that all three videos were viewed 540 times (80+320+140), however, we have no evidence to support that all three videos were watched by the sample. We do not have access to such information, which remains beyond the scope of our research. We do know that our videos have a wide reach.

As one of the accounts that posted our counter-narrative videos was disabled, we lost access to our sample’s long-term responses and were not able to study the long-term effects, including finding out and if they had a positive effect.

As one of the accounts that posted our counter-narrative videos was disabled, we lost access to our sample’s long-term responses and were not able to study the long-term effects and if they had any positive effect.

Intervention

Day One – Analysis

The first counter-narrative video was posted February 16, 2017 at 5:30 PM (GMT) by tagging what remained of our sample of 31 individuals (Fig.1). It took a while for subjects to realize what the video was about because the thumbnail of the video was set to a scene of Cubs of the Caliphate in camouflage outfits with the ISIS flag in the background. Soon after the posting, two people liked it, probably without even having watched it, and assuming, based on the thumbnail, that it was a pro-ISIS video. However, the ones who did watch the video reacted negatively and called the posting account holder an apostate or “Murtad,” claiming “America’s doing by fabricating lies about the Islamic State.” This reaction came from an ISIS member who claimed to be currently in Syria. Strangely, even after such comments were made, this particular account holder did not unfriend or block the sender, which leaves room for speculation of many variants: that he might secretly agree with the video but has to keep a public pro-ISIS stance due to ISIS’ harsh punishments or that he thought the sender mistakenly sent it without understanding it was a counter-narrative video, thus there was no reason to unfriend. It could also be a sign of aggression that this profile who states that he is in Syria wants the sender to see what he is doing and fear him or may also want to learn more about what we are doing. Soon after the first post, an individual sent a link in the message box that was not opened or responded to because of the risk of malware.

The first counter-narrative video was posted February 16, 2017 at 5:30 PM (GMT) by tagging what remained of our sample of 31 individuals (Fig.1). It took a while for subjects to realize what the video was about because the thumbnail of the video was set to a scene of Cubs of the Caliphate in camouflage outfits with the ISIS flag in the background. Soon after the posting, two people liked it, probably without even having watched it, and assuming, based on the thumbnail, that it was a pro-ISIS video. However, the ones who did watch the video reacted negatively and called the posting account holder an apostate or “Murtad,” claiming “America’s doing by fabricating lies about the Islamic State.” This reaction came from an ISIS member who claimed to be currently in Syria. Strangely, even after such comments were made, this particular account holder did not unfriend or block the sender, which leaves room for speculation of many variants: that he might secretly agree with the video but has to keep a public pro-ISIS stance due to ISIS’ harsh punishments or that he thought the sender mistakenly sent it without understanding it was a counter-narrative video, thus there was no reason to unfriend. It could also be a sign of aggression that this profile who states that he is in Syria wants the sender to see what he is doing and fear him or may also want to learn more about what we are doing. Soon after the first post, an individual sent a link in the message box that was not opened or responded to because of the risk of malware.

The first counter-narrative video was posted February 16, 2017 at 5:30 PM (GMT) by tagging what remained of our sample of 31 individuals (Fig.1). It took a while for subjects to realize what the video was about because the thumbnail of the video was set to a scene of Cubs of the Caliphate in camouflage outfits with the ISIS flag in the background. Soon after the posting, two people liked it, probably without even having watched it, and assuming, based on the thumbnail, that it was a pro-ISIS video. However, the ones who did watch the video reacted negatively and called the posting account holder an apostate or “Murtad,” claiming “America’s doing by fabricating lies about the Islamic State.” This reaction came from an ISIS member who claimed to be currently in Syria. Strangely, even after such comments were made, this particular account holder did not unfriend or block the sender, which leaves room for speculation of many variants: that he might secretly agree with the video but has to keep a public pro-ISIS stance due to ISIS’ harsh punishments or that he thought the sender mistakenly sent it without understanding it was a counter-narrative video, thus there was no reason to unfriend. It could also be a sign of aggression that this profile who states that he is in Syria wants the sender to see what he is doing and fear him or may also want to learn more about what we are doing. Soon after the first post, an individual sent a link in the message box that was not opened or responded to because of the risk of malware.

Day Two – Analysis

On the next day of the intervention, the second counter-narrative video interviewing an ISIS guard for 475 sex slaves who were institutionally raped was posted by our anonymized account, Abu Amar again (at 1:30 PM EST), with a caption in the form of a moral question designed to garner attention: “Would it be acceptable to you if your mother, sister or wife was treated in such a way?” The same 31 individuals were tagged in the posting as the previous day.

In less than 24 hours, there were over 270 views, 4 comments and 3 likes. This represented a relatively high boost in rating compared to the first post that had only 46 views in the first 24 hours. The thumbnail chosen to display the counter-narrative video was similar to the first day, showing the ISIS’ flag and soldiers—to tempt sympathizers to click on it. It seemed the question posted alongside the video about the morality of ISIS’ actions drew attention.

At least two accounts tagged in the post did not watch the video, yet they allowed it to be posted in their account, likely because they were misled by the ISIS imagery in the thumbnail of the post. This increased the reach of the video and more people played it. Due to the increased interest in the second video, people kept scrolling through the sender’s profile and watched the first video as well. After the second video was posted, the views for the first video almost doubled, going from 46 to over 80 views. A few hours later the second post had over 320 views (Fig. 5).

Similarly, it was clear that many respondents did not understand the content of the counter-narrative having not watched it. One of the tagged female profiles liked the second video and allowed it to stay on her wall. However, as soon as she realized what the video was about, she removed it and commented on the first video saying, “Who are you that posts these things. Murtad [infidel]” A similar thing happened with an account holder in Syria who at first liked the video and allowed it to be posted on his wall, but upon realizing its contents cursed our account [Abu Amar] and removed it.

Similarly, it was clear that many respondents did not understand the content of the counter-narrative having not watched it. One of the tagged female profiles liked the second video and allowed it to stay on her wall. However, as soon as she realized what the video was about, she removed it and commented on the first video saying, “Who are you that posts these things. Murtad [infidel]” A similar thing happened with an account holder in Syria who at first liked the video and allowed it to be posted on his wall, but upon realizing its contents cursed our account [Abu Amar] and removed it.

Posts were purposefully publicly posted to allow more persons other than the account holders tagged to view it. As a result, our posts could reach out (literally) to anyone. In other words, friends of friends can watch the video even if they were not our “friends” or in our sample. We know that some media jihadis shared the video—they also thus increased the reach—and most likely other ISIS endorsers watched our video as well. The second video received wider views than just the intended sample, making clear this public posting phenomena was occurring. In the second posting, three quarters of the comments came from account holders who were not part of the research sample, but were those we identified as radicalized individuals who were friends of the account holders subject to this research.

The reactions for the second video came from people outside of the sender’s friends list. The first comment was: “Video made by kuffars and filmed in cooperation with kuffars,” the second comment says, “Get out of my sight you filthy munafiq [hypocrite pretender] you are worse than the kuffar [unbelievers [, only the kuffar believe in this, your attempts are worthless. The IS rose with Allah’s help Elhamdulilah, whatever fabrications you create it won’t help you achieve your goals you slave of the devil.”

There were also comments made by an account holder tied to an individual who is currently imprisoned in the Balkans. He is either impersonating someone or is the real person he claims to be. This is something we were unable to verify. His comments were that the videos are a fabrication and that he had been in ISIS and knew better.

His first comment on the Cubs of the Caliphate video was: “May Allah give me a son, so he can become a soldier of faith like him (the youth featured in the video); so he could kill and sever heads for the faith of Allah just like these little kids MashAllah [Praise Allah]. You jealous daule khilafa [second class infidel living in the Caliphate] bakijjaa we tetemedde [an Arabic curse in Latin letters?] your jealousy will kill you, dirty Munafiq [undermining hypocrite], Murtad [infidel], Mushrik [polytheist], Kufr [unbeliever], etc.”.

His second comment was: “Look at the Tetmur jail in Palmyra haha you post photos haha you dirty Mushrik [polytheist].”

He further stated: “Liars, hahah you think I will trust the Mushrik [polytheist] that speaks in this video? Nope, by any means because the IS [Islamic State] is just and we do not treat women that way. I say this because I have been there and there is no place on earth that is as just and great as the IS. You say sex slaves, who cares about them when all we want is to meet Allah? Sex slaves haha the footage is fake. You put up photos of uncovered women (without hijab), which is out of question to happen in Calipha’s Dawla [the Caliphate’s State]. Fi kuli Ard Biidhnilahi Teala amar May Allah paralyze you.”

Also, in response to being tagged to the second video post, one individual subject to this research wrote, “Salamu Alajkum brothers, please forgive me, they tag me in some videos and photos without my permission God bless you.”

Day Three – Analysis

The third day followed the same procedure of posting the third video Join or Defect? but tagged only 23 individuals due to the sample size decreasing as a result of blocks and unfriending. The third video was posted with the caption “Enough.” The video reached 140 views but received no reactions (except one like by a person who just saw the ISIS flag and liked it).

Unfortunately, at that point, the researcher’s anonymized account was deactivated by Facebook. We were also aware that an individual in the sample had taken a screen shot of our anonymized profile and asked people to block it (Fig.7). Once our researcher’s posting account was deactivated, we could no longer view the sample and monitor the longer-term results of posting.

Unfortunately, at that point, the researcher’s anonymized account was deactivated by Facebook. We were also aware that an individual in the sample had taken a screen shot of our anonymized profile and asked people to block it (Fig.7). Once our researcher’s posting account was deactivated, we could no longer view the sample and monitor the longer-term results of posting.

The last two anonymized profiles remain open and we have continued to monitor its “friends,” which include some of the sample of 31 even to the present date, but we did not carry out any further interventions as of yet.

An interesting side note was that the sender for the main posting male account was set up with a lion’s head and a photo of a soldier with binoculars as the profile photo. Interestingly, the last comment (Fig. 7) on the post asking people to report the researcher stated: “When I saw the photo with the binoculars I thought he was a Mujahid [holy warrior], looking out for the Muslims. But no, instead he was spying.”

Gender

Our study was not focused on gender differences although three important observations about gender can be made. First, the use of male and female accounts was necessary for interventions such as this, as some female accounts clearly stated on their bios that they only accept requests from “sisters.” It is assumed this is done for reasons of religious modesty and propriety. Male accounts were also necessary as some male accounts in our sample only accepted friend requests from male accounts, likely for the same reasons. Only three women accepted the friend request from Abu Amar, the anonymized male account running the intervention of posting counter-narrative videos. So, there are clearly women who do accept male requests, but we do not know the break out for these gender variations.

In a parallel study in English we also learned that when the female account created a profile using a picture of an uncovered woman, the fact that she was not covered created a blowback effect as she was not considered appropriate (Speckhard, Bodo & Shajkovci, 2017). Similarly, in both this study and the parallel English speaking study, message requests (40 for the English-speaking account holders) were received, trying to get into a conversation. Those messages were mostly flirtatious in nature, asking along the lines of, “Hi how are you?” and “Where are you from?” Our policy was not to answer any messages due to security concerns, so we also did not study this aspect of gender relations. In addition, in this Albanian-speaking sample our female anonymized account was also deactivated making it impossible to access these messages.

Discussion and Ethical Considerations

As in all our work, our research ethics for this particular study too, was to do no harm. Firstly, in approaching accounts showing serious support for terrorism and making serious movement toward terrorism, we took these accounts to be representing actual individuals. Secondly, we judged these individuals as exhibiting dangerous behaviors both to themselves and others by the fact of endorsing and distributing ISIS materials. Thus we felt that any intervention that might diminish their support for terrorism was in their, as well as the societal best interest We determined that such an approach was highly unlikely to harm them, provided we were careful in how we reported our results compared to doing nothing.

Some could argue that creating anonymized Facebook accounts, such as in this particular research, to engage with the target group and feeding them video material that was designed to look like their usually consumed ISIS content and then use their reactions (e.g. angry, etc.) as impact evaluation carries negative ethical implications. Moreover, misleading the target group into believing they are connecting to fellow movement members without disclosing our true intent, which was to dissuade them from terrorism could be argued to have negative ethical implications. We however judged that intervening in the case of someone moving toward terrorism—even when misleading them into watching our counter narrative videos—was acting in their and societal best interests. Anyone who is stopped from joining a terrorist group, or worse carrying out a terror attack by encountering the words of an ISIS insider denouncing the group might translate to a life saved, if not hundreds of lives saved. The ethics were clearly in favor of carefully carrying out this study.

This study had two goals: Firstly, to learn if we could reach ISIS supporters, endorsers and distributors on Facebook. Secondly, if we could meaningfully engage with them, hopefully to diminish their support for groups like ISIS. In this study we successfully demonstrated that we can reach our target audience. As far as meaningfully engaging with them, the comments although disturbing made by the sample participants demonstrate that they engaged with our materials and thought about them to some extent. This was a short-term study fraught with difficulties in observing effects so we cannot say that we necessarily dissuaded participants from endorsing or supporting ISIS. However we do know we reached them, including their followers and managed to engage many with our counter narrative materials. Given the alternative, of doing nothing and allowing ISIS endorsers and distributors to carry on with no intervention other than law enforcement, we judge this as a success.

We have, and continue to, focus test our videos with vulnerable populations worldwide. In such offline, face-to-face interactions, our research ethics is to first create rapport and a relationship of trust with our research participants (e.g. vulnerable population) before videos are shown to them. This also holds true for this and our ongoing online focus-testing endeavors as well. However, given the importance of evidence-based research on CVE, we also felt that using anonymized accounts in some cases such as this was necessary, as highly radicalized individuals are highly unlikely to accept friend requests from openly identified researchers.

While the videos used during our short intervention could be directly linked to the work of our center, given the logo displayed on each of our videos the decision was made to protect the identities of our researchers for this study. That was judged as necessary and important, especially when dealing with highly radicalized individuals who publicly endorse ISIS, as in many cases these account holders are dangerous and may even be currently fighting abroad with ISIS. Our logo on the materials however was kept intact to add authenticity to our intervention attempts, which are based not on government propaganda efforts but our years of researching the psychological motivations for joining terrorist groups. We firmly believed that the benefits of being open in that regard about who we are and what we do outweighed the risks of hiding our identities.

Leveraging Facebook is just one of many ways of generating evidence from social media platforms to test the utility of our video products with vulnerable populations. A more controversial approach, similar to our study in some cases, is to create anonymized profiles to befriend our target audience. We carefully weighed risks vs. benefits of engaging in the study, coupled with the fact there are no clear ethical guidelines on performing Internet research with vulnerable populations online, and considered a number of ethical challenges facing our research. In this regard, we opted for the best available alternative (Elovici et. al., 2014) and did not directly interact with our subjects other than to share and tag the counter narratives to their accounts.

Likewise, the research was conducted with a careful consideration of ethical concerns related to data collection, protection of research participants’ identities, and data storage. In this regard, our research design was fully rooted in ethical guidelines for academic research, including guidelines on Internet research with vulnerable and extremist individuals online.

To ensure confidentiality of our research participants, we did not include categories of personal information (e.g. date of birth, an alleged commission of a crime by a participant, proceedings for offence committed and court sentences related to our participants, etc.) that would be considered as sensitive personal information under law (e.g. EU). We also excluded personally identifiable information on our research participants’ social networks as it would make it easier to identify their identities, even in the case of those who utilized pseudonyms in their accounts. We only focused on the general picture—that is, on the ecology of collective behavior of our research participants as opposed to individuals. Our goal remained on identifying information relevant to our central research questions and assessing the overall impact of our educational research materials on ISIS-endorsing and ISIS-supporting individuals identified on Facebook.

Despite the fact that our intervention took place in an online environment, the research involved considerable amount of risk, although most of that risk was to the researchers rather than to the subjects. To minimize potential risks, we established pseudonyms and anonymized Facebook accounts in some cases to gain access to our target group and minimize the potential for risk for the researchers. That said, because our videos could be linked to our center and the names of the researchers following the publication of the findings may become known to some of the subjects studied, there is always a possibility of risk of being exposed to physical danger in real life.

We also considered legal ramifications of engaging in online research and the potential to violate counterterrorism laws of countries where our research participants reside. To achieve that, we developed research protocols that ensured a significant degree of protection. To demonstrate, we only uploaded our videos into respective Facebook accounts and avoided dialogue with our participants, which could have potentially led to legal issues and implications. We made sure that our presence in the Facebook account spaces did not constitute an entrapment.

Moreover, given that law enforcement might have been active on Facebook seeking for actionable intelligence, we only collected data deemed to be critical to our research, all in an effort to avoid interfering with any ongoing law enforcement activities and investigations online. Equally important, our research was conducted over a relatively short period of time, and we avoided extended contact with our participants to potentially avoid legal or ethical implications (UNODC, 2012; Stern, 2003; Davis et.al.,2010; Markham & Buchanan, 2012; BPS, 2014).

Some could argue that if any reactions, including negative, could be counted as successful intervention, then there can also be counter-productive interventions, which actually might foster radicalization processes by generated negative emotions or further fueling the extremist ideology (e.g. the sense of being infiltrated by spies or “infidels” trying to trick them, etc.). From a psychological standpoint, it is important to acknowledge the potential impact when ideologically attenuated individuals view videos such as ours (e.g. cognitive dissonance). It is also important to acknowledge the potential impact on those who are unsure of what to believe and are searching for ISIS propaganda material, as it is to discuss if our counter-narratives could impact human cognitive aspects or actions in positive or negative ways. In this regard, we are cognizant of the fact that while our counter- narrative videos have a huge potential to make a positive difference in the fight against ISIS, there is a small possibility for potential for harm in the possibility of raising even more defiance from existing governance. The potential for such harm is minimal, however. For instance, our counter-narratives underwrite [initial] sympathy towards ISIS cadres as human beings versus demonized “monsters”, as often depicted, given our defectors were at some point in ISIS as well as the many reasons for wanting to join, without validating the violent means that the terrorist group propagates. We highlight human costs of engaging in terrorism both for the recruit and those harmed by the group, which serves in opposition to sleek and deceitful ISIS propaganda videos. In addition, our direct targets to be illegitimatized are not potential recruits, but rather the terrorist group and the terrorist leadership. In other words, our overall objective is to target the terrorist group and discredit them in the eyes of potential recruits to save potential recruits from the costs, including loss of their own and lives of others, of engaging in terrorism. [1]

As the authors of the study, we are cognizant of the fact that certain manipulations online, such as feeding video materials to vulnerable populations consuming and promoting ISIS material, may potentially lead to negative side effects, such as change in mood or change in self-esteem. In addition, because this was online research, the participants could have withdrawn from Facebook without notice, complicating any prospect for intervention. That said, given that our video materials “are not expected to create more extreme reactions than those normally encountered in the participants’ lives [given they are already consuming ISIS materials]” (BPS, n.d.), we have minimized the prospect of causing any psychological harm.

In addition to a number of aforementioned measures introduced to facilitate data collection and ensure an ethical research process without placing us, as researchers, or our research participants at risk, we also ensured that our data are stored properly and that no unauthorized persons aside from the research team had access to the data. We also will ensure long-term storage and securing of the data collected (e.g. password-protected files, storing data on secured servers, etc.).

Conclusion