Mona Thakkar & Anne Speckhard Despite notable repatriation progress in early 2023, involving 14 countries…

An ISIS Bride on the Run

By Anne Speckhard

As published in Homeland Security Today:

President Trump had only days earlier greenlighted Turkey’s invasion into northeast Syria, when 26-year-old Belgian ISIS wife, Bouchra Abouallal, imprisoned in the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) Camp Ain Issa, suddenly found herself able to escape. A Belgian journalist recounts receiving audio messages from Bouchra in which she speaks frantically with the sound of bombs falling in the background about being in flight with her sister-in-law, Tatiana Wielandt and their six small children. “She told me that the camp had descended into complete chaos and that she is on the run,” the Belgian journalist recounted. “She is desperate and trying to get to Turkey.” Unarmed, these two women are right now running toward the bombings and conflict, trying to cross into Turkey where they hope to be able to turn themselves into the Belgian consulate and make their way home—hopefully to safety.

Up until last week, Bouchra and her sister-in-law, both formerly strong supporters of the Islamic State ideology, were imprisoned among 12,000 other women and children, 265 of them wives of foreigner terrorist fighters with 1,000 of their children. Only a month earlier, in September of 2019 I interviewed Bouchra in Camp Ain Issa where she told me that she was done with the Islamic State.

Bouchra is a Moroccan immigrant descent Belgian, born in the second largest city in Antwerp where she was first exposed to the virulent ideology that helped to create ISIS. As a teen growing up in Antwerp, Bouchra wasn’t particularly religious. Her parents divorced when she was 16. Sitting across from me, perched in her Islamic robes and headscarf on the sofa of a small interview room, as we sweat under the Syrian heat, Bouchra recounts, “I was Muslim by name, but very moderate.” Her family was well-off but there was “lots of arguing and bad feelings,” so like many girls from troubled families, Bouchra married young, at age 18. Working as a hairdresser, she recalls, “I was not a party girl, [but] I liked to hang out.”

The poison of ISIS reached Bouchra through her brother. “My brother started practicing Islam,” [They] were part of Sharia4Belgium. That is how I married my husband,” Bouchra recalls. Sharia4Belgium was an extremist Salafi organization that called for Belgium to come under shariah law and an outgrowth of the extremist UK preacher Andjem Choudary whose hate-filled ideas of creating a shariah state in UK spewed across the channel into Netherlands and Belgium where they also took solid roots.

Through Sharia4Belgium’s preaching, dozens of Muslim youth discovering a newfound identity in Salafi messages instructing them to return to the “true” Islamic faith and embrace the idea of spreading shariah across Europe. They joined street preachers and activists, who when the Syrian uprising turned violent also began preaching that the Muslims had a duty to make hijrah, that is migrate to lands ruled by shariah law, and to fight jihad on behalf of their Muslims brothers and sisters being subjected to Assad’s atrocities.

Sharia4Belgium grew in strength as Assad continued his violence and ISIS emerged in Syria with Baghdadi proclaiming his new Caliphate. Suddenly scores of youth from Antwerp and nearby Vilvoorde began quietly slipping out of Belgium one by one and in groups of two to five, disappearing into Syria.

Ultimately, but not until it had taken its toll of Belgian youth, Sharia4Belgium was designated a terrorist organization and its leader, along with 45 of its members, were convicted on terrorism charges. Parents of worried youth who alerted the Belgian police at the time, have since told me that these officials did nothing to stop their sons and daughter’s exit and descent into hell. Instead these distraught parents were told that it was not illegal (at the time) to travel to Syria and there was nothing the police could do to stop them. Belgian security officials have likewise privately admitted to me that at the time they thought this was a convenient means of “flushing the Belgian toilet” and thereby ridding themselves of these troublesome militant jihadis. By turning a blind eye as they left in troves for Turkey to cross into Syria, first to fight Assad and later to join ISIS, the Belgian police simply hoped they were taking a one-way trip to Syria and would either die there, or at least never return. It was, according to these police, a good plan to rid themselves of these trouble-makers, that is, until they began returning a few years later, to launch attacks like those carried out in the Bataclan in Paris and the bombings at Zaventem airport and the Schuman metro in Brussels that killed dozens and injured hundreds.

Boucha’s brother was one of these young men caught up in the excitement of the times. “[In 2012,] my brother came with news that he wants to go to help Muslims,” she recalls. “He left in October [2012.] In December we were supposed to go with him.” Bouchra recalls her frustration in Belgium of following their new and strict Salafi interpretation of Islam, explaining, “It was difficult to follow your religion [in Antwerp]. There was a niqab ban and there were many bans against Muslims.”

Trading a vision of being able to live in an Islamic utopia for the safety of Belgium, Bouchra and her sister-in-law Tatiana, traveled with their small babies to Syria to join their husbands. The dangers in Syria were real, however. “My brother got killed in July 2013,” Bouchra recalls. “They were not part of Jabat al Nusra,” she explains referring to the Syrian arm of al Qaeda. “And there was no ISIS yet.”

Only a month passed before Bouchra would also become a casualty of war. “I got injured in the end of November,” she explains. “I got shrapnel in my shoulder and face. I spent one and a half months in the hospital. That’s when I realized I am in a war area and we left,” she explains, recounting how she and Tatiana decided to make their way out of the chaos back to Belgium.

“When I left Syria, I was pregnant with my second,” Bouchra recalls. Back home in Antwerp she received bad news. “[My husband] was killed. He was part of ISIS at that time,” she recounts. “He knew I was pregnant.”

“It’s a nice life in Belgium,” Bouchra explains of her contradictory feelings upon her return to safety. “But as long as you have this ideology it’s a hard life.” Speaking of how she and Tatiana fell under the scrutiny of the security services, due to having been married to jihadi fighters she recalls, “When they give you the name terrorist, whatever happens, they will knock on your door for every single thing. The last time, they raided our house. We had pressure from the people, the government, the [Belgian] federal police,” she explains. In Belgium, like other big cities with a terrorist problem the police raids are often carried out with special forces units dressed in helmets and flack gear. “Two or three times they raided our houses,” Bouchra recalls. “They take us for interrogation. Then we go back home.”

“It’s a big mess when they take you, and your children pull your dress and scream, ‘Mommy!’” Bouchra recalls her eyes widening as she remembers the children’s distress. “People told us to come back to Syria [where] you can live.” By comparison to being hassled and terrified by the Belgian police, Bouchra and Tatiana decided their friends living now under the ISIS Caliphate were right and they left again for Syria—this time to join the Islamic State Caliphate.

“[I] Ieft [Belgium in] August 2015, [traveling with] friends of my husband,” Bouchra explains. “You know when you are pushed in a corner and you are trying to find a new way out. We were very naïve,” she explains. “[We] traveled with two kids.”

This time fearful that the police would stop them, they avoided the airport and travelled by car until Bulgaria. “Someone picks us up in Holland and takes us to Bulgaria and another guy comes and smuggles you into Turkey,” Bouchra recounts of their indirect journey. Bouchra explains, “From moment you are in [Turkey], you are in the hands of ISIS. You stay with Turkish families, [and move] from one family to another,” she explains like many others who have told us about the highly organized ISIS network that existed inside Turkey to move ISIS fighters into Syria. “They are part of it, part of the Islamic State,” she says referring to these Turkish smugglers. She explains that they are “sponsored” by ISIS who were paying for their services. “I got money in Turkey, money from ISIS,” Bouchra recalls, “but I had to pay it to the smuggler.”

“I was scared,” she recalls, although she was also positive about the risks she was taking. “I was actually thinking I’m going to a better place for my children. As long as you have this jihadi ideology, you are willing to go to anything,” Bouchra explains. “If you go to live under Islam, you know that they are fighting, and you know that you are going to jihadi ground.”

“I thought I’d go to Paradise if I got killed,” Bouchra explains how her jihadi beliefs gave her courage. But she found very quickly that what she’d been taught in Sharia4Belgium about going to the Caliphate turned out to be lies. “Everything was a lie,” she recalls. “From the beginning, there is no Islam and no Islamic State. There was never shariah law.” Explaining how it was all a chimera designed to fool her, and the other forty thousand immigrants that streamed in, eight thousands of them leaving the safety and comforts of Europe, to live in an utopian Islamic State, she explains, “When you reach the place, people from outside, people don’t know how it is to live with them. [But,] when you live with them, you see things you don’t see from outside, and people who talk, don’t tell you the truth, or you wouldn’t come.” Looking back to how she was lied to, Bouchra explains, “I feel everyone tricked everyone. Everyone who calls [to come to the Caliphate] lies.”

Bouchra and Tatiana were smuggled from Istanbul to enter Syria in al Bab. “They put me in a woman’s house, a madafa,” she recalls. “That is the biggest nightmare that can happen to you. That’s reality under your feet when you enter.” The madafa that Bouchra was but in was run by

Moroccan women “There were many guards and so many children women. [No one had their] own room. [There was] no privacy. It was dirty and there were fights.” There were 70 women crowded into the house that Bouchra was enrolled into.

At that time Bouchra didn’t know that the external security apparatus of ISIS, the ISIS emni were already working on sending sleeper cells to strike in Europe. “I didn’t know they were sending people back to attack,” she recalls, “but I found it very strange that they took our passports. I heard they are taking passports of Europeans to make fake ones. They were not taking passports of all, [but] mostly of the Europeans.” As she entered the Islamic State, in the Syrian town of Rei, the ISIS intake personnel took her Belgian ID card, her phone, laptop and Belgian passport. She never saw her identity documents again.

Bouchra stayed in the dirty and overcrowded ISIS madafa for two weeks until she found her way out. “[I became] a second wife,” she recalls. Her new husband, “Bilal took me to al Bab to live with his first wife. I didn’t like her,” Bouchra recalls and the marriage didn’t last long. “I was not even one year married to him,” Bouchra explains. “He was fighting [and] aggressive.”

At that time Bouchra and Tatiana had become infamous in Belgium for having gone to Syria only to return and use the Belgian healthcare system to have her second child and then slip out again, out from under the now more watchful eyes of the Belgian security services, to join ISIS. It created an angry furor among nurturing Belgians who felt betrayed.

Referring to her husband, Bouchra explains, “He did a lot of things under my name. He knew our names were well-known. He threatened Belgium with my Facebook account,” she states. Indeed, in that time period Bouchra’s Facebook account included ugly threats back to her fellow Belgians, aimed particularly to the security services who had raided her home in Antwerp. “Your system has failed oh Belgian state,” Bouchra’s Facebook page read as it also taunted the Belgian federal police who she claims had hassled her. “You were watching us 24/7 and you still haven’t managed to stop us. Why? Because Allah is the best planner (…). Her threats continued, “We have left because we believe that it is a duty for every Muslim. To the policeman who threatened to take our children away, I can say that my children will turn yours into orphans, with the will of Allah.”

Bouchra now claims that it was her husband who wrote these hateful postings on her Facebook account. Whether it is true, or not, is impossible for me to know as I listen to her speaking gently now. I can only see that she now appears to hate ISIS, a group she once thought would offer her a better place than Belgium to practice her Islam. “He ruined my life.” Bouchra tells me. “I was always locked up in a room. He would take my phone and do as he likes.”

In ISIS, the women were required to have male chaperones who accompanied them on the streets and in taxis and generally took responsibility for how they dressed and otherwise behaved. Following traditional Islamic culture, women had an important role in the family but in ISIS they lacked any real rights. “When I tried to divorce him,” Bouchra explains it was nearly impossible. “It is very ,very difficult to divorce. [Inside ISIS, the] woman is always wrong, the man always right. You have to shut up and obey.”

Bouchra escaped her ISIS husband by running away to the Dutch friend of her first husband. “He gave me shelter and went with me to the court and arranged for me to get divorced. He had connections there,” she explains. “If you don’t have connections [you cannot].” This was one year into her saga in 2016 and she had already two ISIS husbands under her belt.

“After this I went to Manbij, then to al Bab, again from women’s house to women’s house. Then I tried to go to Raqqa. It was very hard. Everyone I talked to who was saying they would help me was actually a jackass. They said, if you want us to help you, you have to marry one of us.” Bouchra had had enough of ISIS marriages and flatly refused. “So, I was on the streets with my children, 2 and 4 or 5,” she recalls.

But she couldn’t hold out. “I got to the point that I don’t care anymore, and I thought that the first guy who can come and give me shelter, I will marry this guy, and I continued to make stupid decisions in my life.” Finally, giving in to despair she recounts, “I was on the streets with my bags and everything and I went to the [ISIS] courts and said, ‘Help me I want to get married. I need to go somewhere.’ That was a marriage of 1 to 2 months, a worse marriage than the previous one. He was Algerian. It was a horrible marriage. He beat, raped, whatever you can. After this I went and lived with Tatiana [her sister-in-law] in the house and we tried to escape [ISIS].”

Escaping ISIS isn’t easy. It takes courage, money and connections. Bouchra had the courage but lacked money and connections. “We tried smugglers so many times,” she recounts. “They asked a big amount of money.” She also begged her family back in Belgium to help her. “I talked to my mother and my uncle came to the [Turkish/Syrian] border to try to take us out with smugglers, but it was impossible. Everyone had their eyes on us because we had already left one time. Every move you do, there is always someone watching you.”

Bouchra and Tatiana were in Raqqa. “There was sometimes bombing at that time,” Bouchra recalls of the Syrian and later the U.S.-led coalition air assaults on Raqqa. “So many times, we got in the hands of the emni,” Bouchra recalls.“We had three warnings. We got arrested.” Seeing their difficulties, a Trinidadian friend advised Bouchra that as a group of women it might be to hard to get a smuggler, but her friend said, “There is one guy who wants to go out. if you want to marry him you can try to go out with him.”

“Then I finally make a good decision and I married my [current] husband,” Bouchra states. This fourth ISIS husband had quit the group and was also trying to get out. Her new husband had back luck, however. “Three weeks after I married him, he got locked up by the emni. He spent one and a half months in their prison,” Bouchra recalls. During his imprisonment, “We were always hiding,” she recounts. Being black, her new husband couldn’t pass as an Arab and no one wanted to risk trying to smuggle him out, as he attracted attention. “He told me, ‘It’s not working out, let me try alone,” Bouchra recalls. He husband made the necessary contacts for her to be smuggled when he was released from ISIS prison and the couple followed the ISIS movement from Raqqa to the neighboring city of Mayadeen. “I went to a smuggler in Ashara,” Bouchra states of yet another small Syrian city on the path that ISIS members took fleeing bombing, a journey that ultimately ended for many of them in Hajin and Bagouz. “That’s when I got arrested by the emni,” she recalls.

“That’s the worst thing that can happen to you. You think khalas, [enough!] You will not come out again. They have no mercy. They took me and Tatiana,” Bouchra recalls of the ISIS emni. “My children were with my [female] friend, the Trinidadian one. I stayed one week in the prison. There was a lot of threatening, ‘We have to fear Allah. We are living in an Islamic State. How can we go to an infidel state?’ We have to promise not to run away, or you can be killed. You sign a contract.” As others facing similar threats from the ISIS emni have told us this is a contract that is signed in your own blood and it says that if you are caught again trying to escape ISIS you agree that they have the right to execute you.

“You are moving from town to town,” Bouchra recalls, her eyes wide with remembering the fear. “My husband is trying to find smugglers and in the end he found us a smuggler in December of 2017. [My husband] got us out, but he was not able to come with us,” she recalls with admiration filling her voice. At the time however almost all smugglers could only get their clients as far as the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) territory—there was no more smuggling into Turkey and back home to Belgium. Those exits were now blocked except for those with a lot of money and very good ISIS connections.

“In the SDF [custody,] I spent two months in prison here,” she recalls referring to her current location in Ain Issa Camp, “then to Camp al Hol.” Bouchra has been in SDF custody for two years at the time I’m speaking to her and wants to be taken home to Belgium. But although she claims to no longer follow the militant jihadi ideology she picked up from Sharia4Belgium and doesn’t see herself as a threat to Belgium, the politicians and general public back home don’t see her that way. They remember that she already came home once, lied to the police and slipped back out to rejoin ISIS. In their eyes, she apparently only came home to use the Belgian hospital and social welfare system to birth her baby and then turned once again against the country that provided for her. Bouchra however doesn’t see herself as a threat anymore.

“I just hope the Belgian state security will be fair,” she explains, “because they know the truth. We were really trying to leave [ISIS], because it was a big mistake.” Rudi Vranckx a Belgian journalist from VRT has come to make a TV documentary about the women, and their mothers have also banded together to try to pressure the Belgian politicians to return them home, but nothing seems to be working.

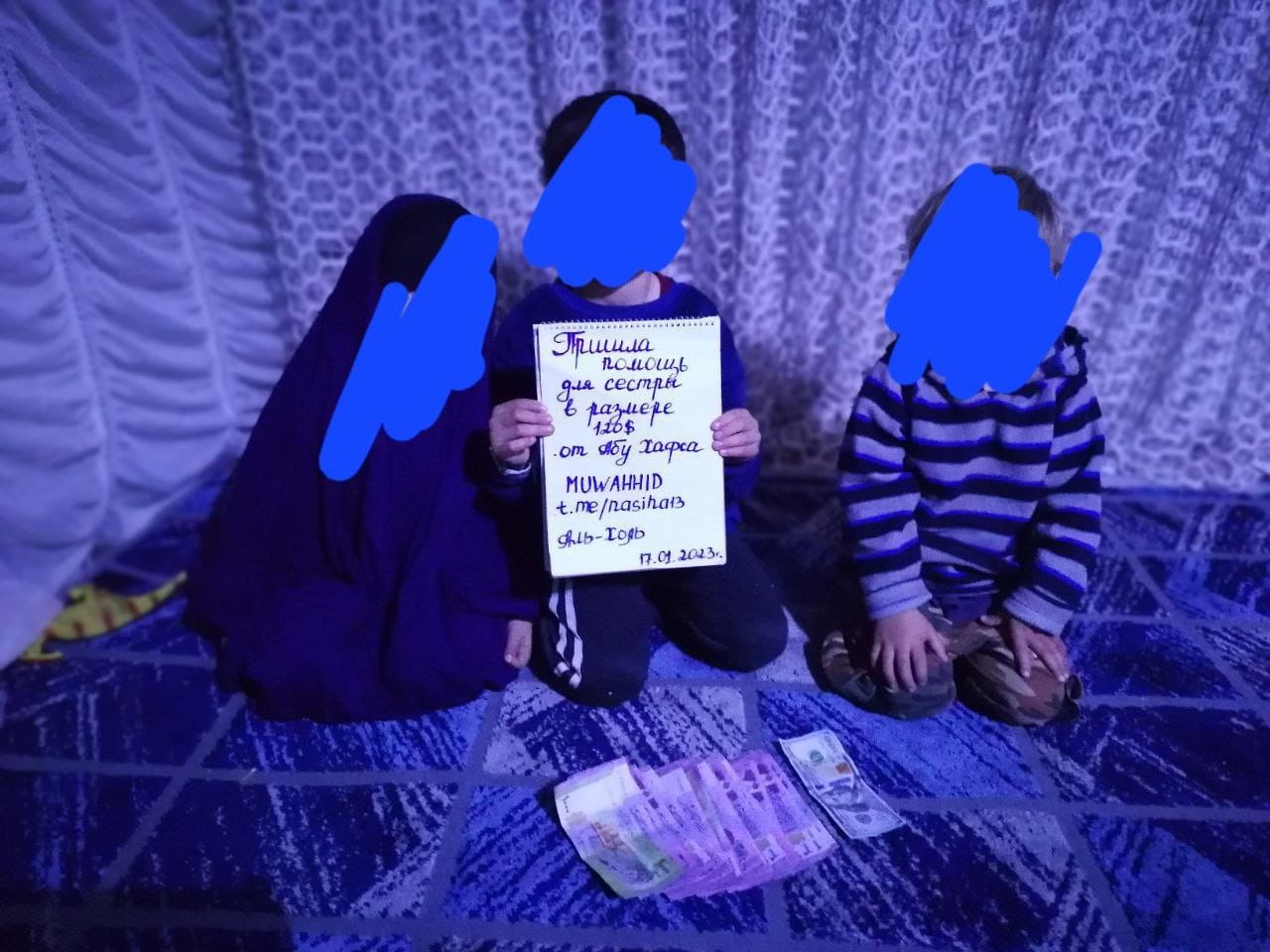

Life in the camps is hard. Having interviewed women in all three camps (Hol, Ain Issa and Roj), we have been told about Typhus outbreaks in the camps that killed both women and children, of women and babies dying in childbirth, of a lack of vaccinations, poor food, and tents that don’t keep the heat out in the summer and are freezing cold in the winters.

“My [5-year-old] son has asthma,” Bouchra tells me as I wonder if I’ve got my inhaler along with me. This is the second time we are hearing about a Belgian child that has asthma in the camps where dust swirls around in dark brown clouds on some days. I know how scary it can be not to be able to breathe and how dependent one can feel on having an inhaler to open up blocked air passageways. The last mother who told us about her four-year-old son said he often turned blue as he stopped breathing and she feared he’d die in front of her. On our second trip to her camp we bought him asthma medicine and delivered it, but I worried that we might not have gotten the correct dosage for a child and the medicine could also kill him.

“We have no treatment,” Bouchra continues speaking of her son’s asthma. “I had to take him a few times to the hospital,” she explains about the medical situation in the camps. Doctors and medical care come with delays and it’s third world quality. Speaking of the Belgian journalists and the small medical team they brought with them to establish DNA connections between the Belgian mothers and their children and to examine the children’s well-being, she adds, “They brought me two or three inhalers. It’s mostly when the seasons change, when it’s hot from cold and before the summer. The worst time is in spring. He really struggles to breath. He turns blue.” I shift about in my purse and briefcase willing my inhaler to be with me so I can give it to her. I don’t expect to have a problem on this trip, and I know how one can feel they are going to die when no air comes, and terror makes it even worse. “I also have asthma,” Bouchra admits.

“I gave birth to the baby in al Hol,” she continues. “It was very difficult. I had a

a c-section [then and I was] sleeping on the ground, after a c-section,” she states her voice drifting off as a look of exhaustion fleets across her face. Looking back at all her losses in making the decision to join ISIS, Bouchra states, “I lost my brother, my husband, my health. I could not lift my arm. It was just sadness [here].”

Trying to put herself into the shoes of those who fear her back home she is able to empathize, “I know people are afraid [of us]. I can understand that. Even I was a part of them [ISIS], and I am afraid. For one part of Belgium I am a terrorist, for another I’m an infidel,” she states referring to how she and Tatiana are now reviled both by her fellow Belgians and by ISIS itself.

“We live now still with fear,” Bouchra explains about the ISIS enforcers inside the camp, “because we know that there are people who are supporting ISIS, and I think it’s a bigger amount than we think. There are [also] people in Belgium supporting this thinking. They see us as infidel. They see our blood as halal [permissable to take].” Indeed, we have heard about ISIS women who still are one hundred percent committed to the ISIS Caliphate who act as ISIS enforcers in these camps. These women go from tent to tent telling the other women that their husband put them in the camps while they are regrouping and regaining their strength and that the ISIS Caliphate will soon rise again. They pass messages each time ISIS leader, Abu Bakr al Baghdadi gives a speech and then continue to preach the ISIS ideology to anyone who will listen.

According to Bouchra there are 20 to 30 ISIS women in Camp Ain Issa who carry on in these roles. The Women’s Protection Unit (YPJ) guards confirm this stating that there is a very charismatic Tunisian woman who preaches in the camp and others who go around beating the other women and attacking them with knives if they speak against ISIS or stop covering themselves. These women also set the other women’s tents on fire or threaten them at knifepoint. Camp Hol is even more violent with these ISIS enforcers holding shariah courts at night and even beating and stabbing to death a number of women. In Camp Hol one ISIS woman stabbed a male YPG guard in his back and very recently a gun fight erupted there in which it was claimed by the SDF that one of the ISIS women had managed to get a pistol.

“In Hol I had a lot of threats and fights,” Bouchra recalls. “I had scratches, scars on my body. They attacked my child,” Bouchra explains. “One time she was in the tent when she was only 11 months old. A big stone was thrown into the tent. Thank God, it just missed her face.”

Looking around her like a trapped animal Bouchra explains, “I think here there is more fear [here inside the camp] than when I was living in ISIS. When you are living in ISIS, you are afraid, but you go in your house and close your door. [But, here in the camp it is a] small Islamic state surrounded by a gate, with emni women, pro-ISIS people, Iraqis who are pro-Baghdadi…” she says as her voice fades off. “I am always protecting my children from this. I keep them from their videos and songs.” When I look confused, she explains, “Children are singing this kind of stuff. They sing, ‘Caravan, caravan,’” Bouchra explains, referring to the ISIS songs that encourage adherence to their strict and violent beliefs.

Bouchra wants to denounce every aspect of ISIS but is also afraid while living among these violent enforcers. Although she gives me permission to show her face and use her real name she is also fearful when looking ahead to when she goes back to Belgium to speak out too much against the group. I know how she feels as I also worry when I give a speech against ISIS in Brussels, that some random ISIS follower could show up with a knife or a gun. “I have too many things to say about ISIS,” she explains. To counsel others in not making her same mistake she advises, “I think people should learn what real Islam is before they go in for an idea like this. They [ISIS recruiters] snatch at people who are just starting in their religion and come with the most extreme things. They have a big influence on the youth, people like me,” Bouchra explains. Looking back to her teen years in Antwerp she recalls, “I had a good life before I started practicing Islam. I went out with my car; I had a boyfriend and we went out…then [when in the jihadist thinking] you have to do the most extreme things. You have to do this and this and this.”

Many of the Europeans, particularly women that we have interviewed have told us that they were attracted to the ISIS Caliphate believing that it would afford them a place to practice their religion without being hassled, that they could wear a niqab without being spit on or insulted on the streets. I ask Bouchra who says she left Belgium the second time because she was tired of the police raiding her house what she now thinks about practicing her Islam in Belgium.

“Yes I can practice,” she answers. “I think I can perfectly have my religion in Belgium,” she continues. She wants desperately to return home. “I miss the chocolates,” she says taking another melting Belgian chocolate that I have brought along with me and now offer to her. “I miss my mother, I wish I could get up, and go to sleep on her lap,” she says as tears fill her eyes.

Bouchra tells us how hard it is to watch others who haven’t even given up their devotion to ISIS being taken home by their countries while she and Tatiana are left to languish in the camp. “Those who came out of Baghouz, they are so diehard. When they leave this camp for their homes, they pick up the sand and wipe their clothes with it, like this is the last time.”

“Coming to ISIS was the best deradicalization I could have,” Bouchra explains. Indeed, we keep being surprised by the spontaneous deradicalization that has, and continues to happen even without any formal rehabilitation program, among the imprisoned ISIS men and women who became totally disillusioned of ISIS as it went down. As the Iraqis managed to have food, money and cars up to the last moments in Baghouz while foreign fighters literally fed their children grass and watched some of them starve to death, most foreign fighters became angry and finally understood that the Iraqis had been using them all along. “I think [Baghdadi is] a dog, a pig that lied to us,” Bouchra tells me. “I hope he will burn in hell. I have no words that are enough for him. He made genocides, massacres. When we first came here I read in the Syrian paper that we became meat for cannons. It was really true. No one was allowed to leave. A lot of Belgian men got killed by ISIS. I think a lot of Belgian men saw it was a lie,” she now states, with bitter regret filling her voice.

“I really think if they keep this camp a new Islamic State will come out of it,” Bouchra tells us. “There is so much radicalization coming out of this camp.” Just as the YPJ guards have told us, she repeats, “There are women going tent to tent, giving lectures. They want a new Islamic State. They say, you heard Baghdadi? He made a speech, there is a new Caliphate. They are very happy. They are diehard in their ideology.” Bouchra makes a point of saying these diehard women are not the Europeans.

“I hope we go home. I think two years in a camp is enough,” she repeats.

Comparing ISIS with where she came from Bouchra states, “Belgium is a very nice country. There’s no sand, a lot of hygiene. People have respect. I really miss civilized people. Now I live in a cage with animals. I miss so much Belgium. I want to leave Syria and I don’t want to know any Syrians. I don’t want to see Syrians when I’m in Belgium.” Like all trauma survivors she feels much older than her true age. “I’m 26 and I feel I’m 66,” Bouchra says, sighing with exhaustion. “Today I was crying with Tatiana. In our normal life, today would be the first day of school, but our children cannot even read or write.”

Bouchra worries for her children. “One week ago a girl died in the camp here,” she tells me. It’s been over 100 degrees Fahrenheit (i.e. over 40 degrees Centigrade) all week and there is no air conditioning in the tents. Sweat is trickling down my face and body even with an air conditioner in the tiny room where we are meeting now. “She died of heat. She was 5 months old. There is a woman from Netherlands. Seven or 8 months ago, she died from HIV.”

“I am willing to send my children home without me,” Bouchra offers when I ask her if she would. “They didn’t do anything wrong. Please come and take our children,” she says, as though talking to the Belgian government. “Of course, no mother wants to be separated from her children,” she adds with sudden regret.

“[In Belgium], I have a five years prison sentence,” Bouchra tells us. “I accept it. I want my children to go home and go to school. I don’t care if I have 20 years,” she adds. “I make a mistake. The most important thing is I know I made a mistake. I repent. I’m not fighting that I know I have to be punished. This is how it is. You make a mistake you pay for it,” she says.

Although I’d like to talk with Bouchra much longer and also interview her sister-in-law, the YPJ guards in Camp Ain Issa are overwhelmed and have given us only two hours today to speak to two women. We’ve gone over our time limit and they are starting to pressure us to end the interview. As we pack our things to leave, I search one more time for my inhaler. I don’t have it along with me, so I can’t give it to her. Bouchra tells us about the winter coming and how she fears for the cold, especially when the tents collapse under the weight of heavy rains and let all the cold water come pouring in. “I didn’t have time to pack anything when I was moved from Camp Hol she tell us. I only have the clothes I was wearing.” She is wearing a light cotton robe and will clearly be cold in the winter. I take off the long cardigan I’ve been wearing for modesty and hand it to her. One more thing for the FBI to tell me is giving material support to terrorists. At least she’s given up ISIS, so I shouldn’t be guilty for this act of humanity—at least I hope not.

A month after leaving the camp, I’m in Germany watching the news unfold from Trump’s tweet that greenlighted the Turkish invasion of northeast Syria. Bombs and mortar are falling all over the Kurdish areas and the camps are also in danger. In Belgium I hear that after Ain Issa was hit the women began rioting, setting their tents on fire and bursting through the fences. According to the journalist they called, Bouchra and Tatiana waited for a day to decide what to do. Now they’re on the run with six little children between them and no one knows if they’ll make it into Turkey alive. Or if she’s been lying, if they’ll decide to just slip away and disappear again, maybe even being pulled back into the ISIS Caliphate. From what I can tell, it seems Bouchra is sincere about her desire to escape ISIS, never to return again, but now the question is of whether or not she can.

Reference for this Article: Speckhard, Anne (October 22, 2019) An ISIS Bride on the Run. Homeland Security Today https://www.hstoday.us/subject-matter-areas/terrorism-study/perspective-an-isis-bride-on-the-run/

Author Biography

Anne Speckhard, Ph.D., is Director of the International Center for the Study of Violent Extremism (ICSVE) and serves as an Adjunct Associate Professor of Psychiatry at Georgetown University School of Medicine. She has interviewed over 600 terrorists, their family members and supporters in various parts of the world including in Western Europe, the Balkans, Central Asia, the Former Soviet Union and the Middle East. In the past two years, she and ICSVE staff have been collecting interviews (n=217) with ISIS defectors, returnees and prisoners, studying their trajectories into and out of terrorism, their experiences inside ISIS, as well as developing counter narratives from these interviews. She has also been training key stakeholders in law enforcement, intelligence, educators, and other countering violent extremism professionals on the use of counter-narrative messaging materials produced by ICSVE both locally and internationally as well as studying the use of children as violent actors by groups such as ISIS and consulting on how to rehabilitate them. In 2007, she was responsible for designing the psychological and Islamic challenge aspects of the Detainee Rehabilitation Program in Iraq to be applied to 20,000 + detainees and 800 juveniles. She is a sought after counterterrorism expert and has consulted to NATO, OSCE, foreign governments and to the U.S. Senate & House, Departments of State, Defense, Justice, Homeland Security, Health & Human Services, CIA and FBI and CNN, BBC, NPR, Fox News, MSNBC, CTV, and in Time, The New York Times, The Washington Post, London Times and many other publications. She regularly speaks and publishes on the topics of the psychology of radicalization and terrorism and is the author of several books, including Talking to Terrorists, Bride of ISIS, Undercover Jihadi and ISIS Defectors: Inside Stories of the Terrorist Caliphate. Her publications are found here: https://georgetown.academia.edu/AnneSpeckhard and on the ICSVE website http://www.icsve.org Follow @AnneSpeckhard